Coming up this week on Breaking Badness. Today we discuss: Now You See Me, Now You Don’t, You’re A Shining Starlink, and Two Truths and a Lie

Here are a few highlights from each article we discussed:

Now You See Me, Now You Don’t

- In late 2021, Nicholas Boucher and Ross Anderson at Cambridge University released the paper “Trojan Source: Invisible Vulnerabilities

- They presented their findings in Spring 2022, and the recording of that was made available earlier this month

- This research describes how human reviewers are unable to see what the issue in the code is

- What we’re talking about is, your source code us lying to you in a way we’re not used to

- The vulnerability takes advantage of the Unicode spec

- Unicode is code text so that you can support multiple languages (English, Cyrillic, Chinese, Arabic, etc.)

- It also has ways to encode how to display the characters to use (right to left or left to right)

- A question becomes, how would you embed a language like Hebrew or another language read from left to right in something that is otherwise in English (for example if you were quoting Hebrew within English text)

- You could make the coder type the Hebrew backwards

- But what Unicode did was take those characters and flip the direction that text draws when you type it (you would type it in the same order, but Unicode flips it)

- A question becomes, how would you embed a language like Hebrew or another language read from left to right in something that is otherwise in English (for example if you were quoting Hebrew within English text)

- The problem is when you get to the security folks

- The question becomes, can I use this information to make things lie for me, and the answer is, yes

- These researchers played around with the directionality characters and built a couple of applications where directionality controls moved what looked like logic into comments, so a person reading source code would read this and say, “ok this line here isn’t executed unless this condition is met.”

- But the compiler doesn't look at what’s displayed, it’s looking at the action in the file and ignores the direction control character so the control thing gets moved into the comment according to the compiler so the user looks at the code looks at it and says I’m fine with it, but the compiler does something different and that’s really surprising

- That’s where a malicious patch can change how the application behave entirely

- Another layer to this is Machine Learning (ML)

- Again, we read things as they’re displayed, not as they’re encoded

- ML is treating this as another character to learn from

- The researchers also pointed out that copying and pasting adds another layer of complexity

- Sometimes when developers have a problem and they don’t know how to solve it, they look at Stack Overflow or GitHub to see if someone else has run into the same issue and if they were able to solve it (copying and pasting code)

- The problem is, copy/paste supports Unicode, so if the example you grabbed is malicious, you have brought those characters in with you

- This discovery was made out of pure academic research

- Does this help spread badness because it’s potentially teaching bad actors something new?

- Well, you can’t fix a bug if you don’t know it exists

- Does this help spread badness because it’s potentially teaching bad actors something new?

- How do you mitigate something that’s invisible?

- The researchers shared their findings with various organizations who all reacted differently

- The Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) treat it as a bug

- They have a process to fix it. Very responsive because they had a response to it

- ML models really don’t have the structure to have security notices, so they’re reactions varied

- Some people expect ML models to be wrong, so they kind of shrugged until someone really said, no I can lie to your users through this

- Part of the presentation was about the response

- How do you mitigate something that’s invisible?

- A lot of this has been mitigated already

- If you’re using a recent IDE, you should be fine

- What we think will be interesting is the Natural Language Processor (NLP) libraries

- Twitter, for example, has a function where you write a tweet, and they will say, “people don’t tend to write tweets like this, are you sure you want to do that?” What they’re doing is, having a machine learning model analyze it to say, this looks aggressive, we don’t think you really want to send this

- If Twitter gets more assertive about not not posting because something didn’t pass the abuse NLP model, we suspect this will become an arms race with people using non printed characters

- NLP models will be more interesting in this space as this evolves

- A lot of this has been mitigated already

You’re A Shining Starlink

- Belgian researcher Lennert Wouters revealed at Black Hat how he mounted a successful fault injection attack on a user terminal for SpaceX’s satellite-based internet system

- For those who may be unaware, Starlink is one of the many products developed by the eminently controversial Elon Musk

- Part of SpaceX

- It is a constellation of large numbers of small communications satellites that provide Internet access, and one of the very advantageous things about satellites is that they can provide connectivity in areas of the Earth that don’t have other options, like very remote locations on land, or out in the ocean

- Satellite Internet access is not new—it’s been around for at least 20 years or so

- What’s new about Starlink is that it aims to bring the cost of satellite-based access way down from where it traditionally has been, and gives pretty good performance

- In Tim’s previous life as an emergency management volunteer, there was a lot of interest in this as one possible means of alternative communications, since if a big earthquake knocks out your local cell towers and the like, as long as your Starlink transceiver didn’t get crunched by falling debris, and as long as you have some power available, which can come from batteries, you’re good to go

- Someone might take interest in hacking a satellite because if something has electrons flowing around in it, it can be a target for creative experimentation

- Starlink has a lot of reasons that it could be a target, though: it’s high-profile, it’s an interesting technology, some people hate Elon Musk, it’s by definition Internet-accessible (though that aspect doesn’t specifically affect this story, as we’ll see)…anyway, the list goes on

- But being able to control these things offers a lot of potentially interesting things you can accomplish, ranging from just giving yourself free Starlink access to denying service to leveraging unauthorized access into networks

- Lennert Wouters was able to accomplish this by tearing down a Starlink transceiver, studying how it worked, then devised a little microcontroller-based hack module that he connected to the Starlink

- This device leveraged something called a voltage fault injection, which basically caused a momentary short in the hardware ROM bootloader

- This short causes the bootloader to bypass its security protections, and the fun begins there

- The goal here is to basically pwn the transceiver and get into the satellite network, and that is in fact what Wouters achieved, by deploying a modified bootloader.

- Wouters reported his findings to SpaceX through its bug bounty program

- It’s good when companies run bug bounties because

- A.) It properly rewards researchers who put a lot of work into finding bugs and developing exploits

- B.) It acknowledges that all production software and hardware is imperfect, so finding bugs is way better than pretending they don’t exist

- SpaceX responded in a 6-page response to Wouters, congratulating him for the find and encouraging researchers to hammer on it even harder

- They respond specifically to this hack by pointing out that it doesn’t affect ordinary Starlink users, which at least in an immediate sense is true, because you need physical access to the User Terminal (the official name of the Starlink transceiver unit) and you have to have one of these microcontroller devices that Wouters built

- So any individual’s odds of having their UT hacked in this way are very low, and there are pretty easy ways to safeguard against it

- we don’t necessarily know the full extent of what might be possible in terms of least privilege violations once the hacker has access into the Starlink network

- No reason right now to believe that they could wreak major havoc, but it’s hard to prove a negative, so I would hesitate to say that this access method has no way to remotely harm others

- It’s good when companies run bug bounties because

Two Truths and a Lie

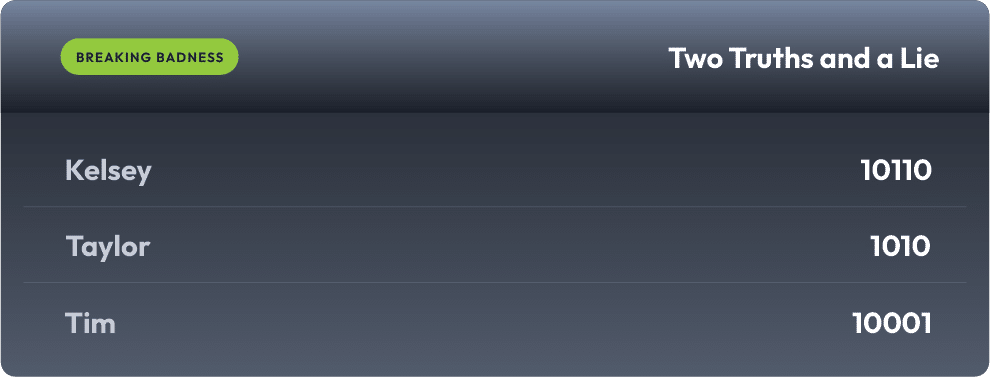

Introducing our newest segment on Breaking Badness. We are going to play a game you are all likely familiar with called two truths and a lie, with a fun twist. Each week, one us with come prepared with three article titles, two of which are real, and one is, you guessed it, A LIE.

You'll have to tune in to find out!

Current Scoreboard

This Week’s Hoodie/Goodie Scale

Now You See Me, Now You Don’t

[Aaron]: 6/10 Hoodies

[Tim]: 5/10 Hoodies

You’re A Shining Starlink

[Aaron]: 2/10 Hoodies

[Tim]: 2/10 Hoodies

That’s about all we have for this week, you can find us on Twitter @domaintools, all of the articles mentioned in our podcast will always be included on our podcast recap. Catch us Wednesdays at 9 AM Pacific time when we publish our next podcast and blog.

*A special thanks to John Roderick for our incredible podcast music!