How Are The Results From A DNSDB Standard Search Ordered?

I. Introduction

This article tackles a simple question (which actually turns out to have a surprisingly complex-appearing answer): “How are the results from a DNSDB Standard Search ordered?”

We’ll answer that question in this article and explain why that answer matters to anyone who makes DNSDB Standard Search queries that return large numbers of results.

Let’s begin by recalling that DNSDB data gets stored “server-side” in MTBL (immutable sorted string) files, as previously discussed in “Passive DNS and SIE File Formats” (see https://www.domaintools.com/resources/blog/passive-dns-and-sie-file-formats/). When you run a query against DNSDB, matching results are selected and returned from those MTBL files.

The results you receive will be the lesser of [the maximum number of results requested by the user via a DNSDB client] and [the maximum number of results allowed per-query by the DNSDB server].

This normally means that authorized users can ask for:

- Up to a million results via an initial query (if the DNSDB client you’re using allows you to ask for that many) PLUS

- Up to three additional “offset” queries (each also for up to an additional million results), again, subject to any limits that your DNSDB client may impose.

See “Getting More Results from DNSDB Using the New -O (Offset) Option” (https://www.domaintools.com/resources/blog/getting-more-results-from-dnsdb-using-the-new–o-offset-option/) for more around the “offset” concept if you’re not already familiar with it.

While four million results is undeniably a LOT of results, DNSDB may “know about” EVEN MORE than four million potential results, at least for some queries. When that’s the case, the subset of results you’ll see (in cases where there are too many results to return them all) is determined by how results are stored in MTBL files, and how the matching results are found and returned.

The results you’ll get from DNSDB are

- NOT sorted so that the results you get will come from the “most important” top-level domains (as if that was something we could all agree upon!)

- NOR are they ordered by count, so you WON’T preferentially see the most commonly seen results (e.g., the results with the highest counts), NOR the most novel/potentially intriguing results (e.g., the results with the lowest counts)

- NOR are they ordered by time, so you WON’T necessarily see the “freshest” or “most recently seen” results (NOR the oldest/most longstanding results).

You’ll simply get results that match your query in the natural order they’re saved in the MTBL files that are being searched.

This is true even if you subsequently sort your results “client side.” Your client will only receive, and can only SORT, the subset of results received from the server, it CANNOT somehow ask the server to consider “all” possible results that match your query, “cherry-picking” and returning just the “best” results after considering your particular preferences.

This means that it is important to understand the natural order of results as they’re saved in MTBL files.

Comprehending that process begins with understanding where DNSDB results originate.

II. DNSDB Observations Potentially Come from ICANN Top Level Domain Zone Files, as well as from Network Sensors

DNSDB API results (as returned by DNSDB clients such as dnsdbq or DNSDB Scout), contain data from two sources — observations from ICANN Top Level Domain Zone Files, and observations from our network sensors. You can determine “which is which” by looking at the time stamp “labels” shown for each result. For example, the following observation (shown here in presentation format) comes from ICANN Zone File TLD data (emphasis added to this sample output):

;; zone times: 2021-05-20 23:12:48 .. 2021-11-28 23:05:03 (~191d 23h 52m)

;; count: 192; bailiwick: info.

apple.info. NS a.ns.apple.com.

apple.info. NS b.ns.apple.com.

apple.info. NS c.ns.apple.com.

apple.info. NS d.ns.apple.com.

On the other hand, the following observation came from sensor data (emphasis added to the sample output):

;; record times: 2021-03-14 19:30:11 .. 2021-11-29 15:06:24 (~259d 19h 36m)

;; count: 2841; bailiwick: info.

apple.info. NS a.ns.apple.com.

apple.info. NS b.ns.apple.com.

apple.info. NS c.ns.apple.com.

apple.info. NS d.ns.apple.com.

When results are displayed in “natural” order, you will always see Zone File data FIRST, if Zone File data is available.

That fact naturally leads to two questions:

i) Why won’t I ALWAYS see Zone File data for a query?

Sometime Zone File data simply isn’t available. For example, the dot edu and the dot mil zones don’t share Zone File data. Country code TLDs also often don’t share Zone File data.

Other times, you might be accessing DNSDB via DNSDB Export (sometimes referred to as “DNSDB On-Premises”). We’re not allowed to redistribute ICANN Zone File data in bulk, so that means DNSDB Export users do NOT receive ICANN Zone File data from us, only the data that originates from our sensors. (We’re happy to help DNSDB Export customers import Zone File data that they themselves have arranged to download directly from ICANN, however.)

Lastly, Zone Files only contain a limited set of Resource Record Types — largely “NS” records plus “glue” records (“A” or “AAAA” records referring to the delegation point’s in-domain name servers), plus a limited number of other “infrastructural” resource records related to the TLD zone itself. If your queries are for pretty much anything else, it’s unlikely that there will be anything in the Zone File data relevant to your query.

ii) When I do see Zone File data, why does it always appear FIRST?

DNSDB uses two sets of MTBL files: one set that contains only Zone File data, and another set that contains only sensor data. DNSDB was set up to search and return results from the smaller Zone File data files first (if they exist and are relevant), and then (and only then) return results from the sensor data files.

III. Some DNS “Lingo”

Before talking more about RRset ordering, let’s briefly recap some of the DNS “lingo” we’re about to use. For example, consider a typical DNS Resource Record (as might be returned as an answer from the Un*x command

$ dig www.domaintools.com

).

We’ll add a “header row” to make clear “what’s what” in the core answer received for that query:

RRname (or "left hand side") TTL Class RRtype Rdata (or "right hand side")

www.domaintools.com. 43200 IN A 199.30.228.112

The above “A” record maps the RRname (or “owner name”)

www.domaintools.com

to the IPv4 address

199.30.228.112.

The resource record also declares that this relationship should be remembered locally (or “cached”) for 60*60*12=43,200 seconds (e.g., 12 hours).

The DNS “class” of this Resource Record, like virtually all Resource Records, is “IN” (“INternet”). (For information on other DNS class values, if curious, consult https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1035 at Section 3.2.4)

The data that’s reported by dnsdbq (see https://github.com/dnsdb/dnsdbq ) in default presentation format is very similar, albeit WITH some added comment lines (denoted by leading semicolons) and WITHOUT TTL or DNS Class data. We’ll use dnsdbq’s

-A1d

command line option to ask just to see results that have been seen within the last day (as of the time this example was run):

$ dnsdbq -r www.domaintools.com -A1d

;; record times: 2015-03-18 20:21:57 .. 2021-11-30 08:49:37 (~6y ~258d)

;; count: 962765; bailiwick: domaintools.com.

www.domaintools.com. A 199.30.228.112

Looking at just the comment lines shown above, those lines tell us:

- The data came from sensor data (and not from Zone File data), since we’ve been given “record” times and not “zone” times

- The first and last times reported are the first and last time we saw this exact result (as of the time this example query was run)

- The count says how many times our sensors saw this exact result across that entire interval

- The bailiwick explains where in the DNS hierarchy this data originated (in this case, it was seen from the domaintools.com zone). For more on bailiwicks, see “What Is a Bailiwick?” (https://www.domaintools.com/resources/blog/what-is-a-bailiwick/)

IV. Key/Value Pairs; Different MTBL ENTRY_TYPEs

With that background, we can now say that MTBL “key”/”value” pairs (e.g., DNSDB “observations” or “results”) are ordered (within the overall Zone File data or within the overall sensor data) by each entry’s “key.”

Each MTBL “key” begins with an ENTRY_TYPE. ENTRY_TYPEs are described in the man page that gets installed as part of the software mentioned in “Passive DNS and SIE File Formats” (https://www.domaintools.com/resources/blog/passive-dns-and-sie-file-formats/):

$ man dnstable-encoding

The current full list of ENTRY_TYPEs is:

- ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET (type byte \x00, decimal zero)

- ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET_NAME_FWD (type byte \x01, decimal one)

- ENTRY_TYPE_RDATA (type byte \x02, decimal two)

- ENTRY_TYPE_RDATA_NAME_REV (type byte \x03, decimal three)

- ENTRY_TYPE_TIME_RANGE (type byte \xFE, decimal 254)

- ENTRY_TYPE_VERSION (type byte \xFF, decimal 255)

Our focus today is going to be on the first of those, ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET. These are the MTBL entries that get searched if you look for an exact RRname such as

www.example.com

in DNSDB. These entries are also what’s used to search for a left hand wildcard RRname (such as

*.example.com

) in DNSDB.

As stated in the previously mentioned manual page, the “key” field for the ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET is a composite field consisting of:

- Type byte. The constant “\x00”.

- RRset owner name [e.g., RRname]. Label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name.

- RRtype. Variable-width integer.

- Bailiwick domain name. Label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name.

- Rdata array. An array of one or more wire-format DNS record data values. Each record data value is preceded by its length, encoded as a variable-width integer.

V. Label-Reversed Wire-Format DNS Domain Names

The “label-reversed wire-format DNS domain names” mentioned in the preceding need a bit of explanation. Assume the original RRname (or “RRset owner name”) is

www.example.com

As stated in the man page, the label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name would then be

\x03com\x07example\x03www\x00

- The \x03 represents the length of the first label (e.g., the top-level domain “com”)

- The \x07 represents the length of the 2nd label in reversed order (“example”)

- The \x03 represents the length of the third label in reversed order (“www”)

- The \x00 is a flag value indicating the end of that label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name.

Given the above, the “label-reversed wire-format DNS domain names” look like:

\x{tld-length}TLD\x{2nd-label-length}2ND-LABEL\x{3rd-label-length}3RD-LABEL[...]\x00

and will be sorted as follows:

- Sorting within the set of ENTRY_TYPE_RRSETs begins with the length of the top level domain:

- First we’d see all results for the root domain (“.”) (which has length zero)

- Then we’d see all results from two letter TLDs (“ac” through “zw”) since there should be no single letter TLDs.

- Then we’d see all results from three letter TLDs (“aaa” through “zip”)

- Then we’d see all results from four letter TLDs (“aarp” through “zone”)

- Then we’d see all results from five letter TLDs (“actor” through “zippo”)

- Then we’d see all results from six letter TLDs (“abarth” through “zappos”)

- Etc., etc., etc.

- Within each of those TLD “length tiers”, TLDs will next be sorted by the value of the TLD itself (in alphabetical order)

- Next, sort by the length of the 2nd-label from the reversed name

- Within each 2nd-label “length tier”, results are next sorted by the value of the 2nd-label itself

- Next, sort by the length of the 3rd-label from the reversed name

- Within each 3rd-label “length tier”, results are next sorted by the value of the 3rd-label itself

- […]

- The final trailing \x00 signals the end of the label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name.

So, let’s assume we were given a very strange/tiny MTBL file with just the following domain names:

. [aka "the DNS root"]

abc.info

af

bbc.co.uk

biz

google.com

host.af

mmcz.co.zw

mx.ucla.edu

www.nic.in

zapp.com

Those names would be saved and returned (perhaps initially counter-intuitively) in the order:

Reversed representation Reason for this ordering

[0] (the root is the smallest possible TLD)

[2]af[0] ("af" 2 character TLD is longer than 0 character (root) domain)

[2]af[4]host[0] (same 2 character TLD, but longer 2nd-level domain)

[2]in[3]nic[3]www[0] ("in" 2 character TLD comes after "af" TLD)

[2]uk[2]co[3]bbc[0] ("uk" 2 character TLD comes after "in" TLD)

[2]zw[2]co[4]mmcz[0] ("zw" 2 character TLD comes after "uk" TLD)

[3]biz[0] ("biz" 3 character TLD is longer than the "za" TLD)

[3]com[4]zapp[0] ("com" 3 character TLD comes after "biz" TLD)

[3]com[6]google[0] (same TLD, but the 6 char 2LD "google" > the 4 char 2LD "zapp")

[3]edu[4]ucla[2]mx[0] ("edu" 3 character TLD comes after "com" TLD)

[4]info[3]abc[0] ("info", a 4 character TLD comes after all 3 character TLDs)

VI. The Remaining Fields Comprising the ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET Key

Recall that we mentioned in Section IV that the fields comprising the ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET key are:

- Type byte. The constant “\x00”.

- RRset owner name [e.g., RRname]. Label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name.

- RRtype. Variable-width integer.

- Bailiwick domain name. Label-reversed wire-format DNS domain name.

- Rdata array. An array of one or more wire-format DNS record data values. Each record data value is preceded by its length, encoded as a variable-width integer.

We’ve talked about the type byte and the RRset owner name. The three remaining items that form the rest of the ENTRY_TYPE_RRSET key are:

- RRtype: The RRtype sorts in ascending order according to the numeric RRtype value (“A”=1, “NS”=2, “CNAME”=5, etc., see https://www.iana.org/assignments/dns-parameters/dns-parameters.xhtml)

- Bailiwick: Bailiwick values are sorted from the most general bailiwick to the most specific bailiwick values), and

- Rdata array (aka the “right hand side” of DNS results). Sorting of Rdata (due in part to the variety of data types that may be present) is potentially complex, and something we will not address in detail for this article.

Let’s now look at a few examples.

Example A): We’ll use dnsdbq to get up to a million “A” records for the arbitrarily selected domain name

vod.uoregon.edu

, from the

vod.uoregon.edu

bailiwick, for fully qualified domain names seen in the last 60 days. The full results for that query in JSON Lines format (with human-readable datetimes) looks like the following (lines wrapped for display in this article):

$ dnsdbq -r vod.uoregon.edu/A/vod.uoregon.edu -l0 -j -T datefix -A60d

{"count":6,"time_first":"2021-10-05 17:15:44","time_last":"2021-10-06 18:59:20",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["34.210.135.53","44.238.165.32","44.239.179.132"]}

{"count":2,"time_first":"2021-10-07 23:30:28","time_last":"2021-10-09 01:44:12",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["34.214.137.119","44.238.165.32","44.239.179.132"]}

{"count":7,"time_first":"2021-10-10 04:34:28","time_last":"2021-10-13 14:16:46",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["34.214.137.119","44.238.165.32","54.69.240.214"]}

{"count":3,"time_first":"2021-10-14 15:11:18","time_last":"2021-10-15 17:04:59",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["34.214.137.119","54.69.240.214","54.187.37.159"]}

{"count":4,"time_first":"2021-10-17 21:38:55","time_last":"2021-10-18 23:58:04",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["34.214.137.119","54.187.37.159","54.213.245.156"]}

{"count":4,"time_first":"2021-11-08 23:30:40","time_last":"2021-11-09 01:35:57",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["44.233.200.82","44.237.40.166","52.12.193.206"]}

{"count":1,"time_first":"2021-10-27 17:26:46","time_last":"2021-10-27 17:26:46",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["44.237.40.166","52.43.178.149","54.187.37.159"]}

{"count":31,"time_first":"2021-11-23 19:39:26","time_last":"2021-11-24 16:23:45",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["44.237.209.101","52.25.117.189","52.88.16.106"]}

{"count":3,"time_first":"2021-11-27 23:45:31","time_last":"2021-11-27 23:45:31",

"rrname":"vod.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"vod.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["52.25.117.189","52.25.186.42","52.88.16.106"]}

That’s rather “visually dense.” If we look at just the Rdata for our results with jq (see https://stedolan.github.io/jq/ ), the fact that the results are sorted by Rdata (when the RRname, Bailiwick and RRtype are constant, as they are for this query) is easy to ascertain (even though we won’t look at Rdata sorting in detail today):

$ dnsdbq -r vod.uoregon.edu/A/vod.uoregon.edu -l0 -j -T datefix -A60d | jq -r '.rdata' -c

["34.210.135.53","44.238.165.32","44.239.179.132"]

["34.214.137.119","44.238.165.32","44.239.179.132"]

["34.214.137.119","44.238.165.32","54.69.240.214"]

["34.214.137.119","54.69.240.214","54.187.37.159"]

["34.214.137.119","54.187.37.159","54.213.245.156"]

["44.233.200.82","44.237.40.166","52.12.193.206"]

["44.237.40.166","52.43.178.149","54.187.37.159"]

["44.237.209.101","52.25.117.189","52.88.16.106"]

["52.25.117.189","52.25.186.42","52.88.16.106"]

Example B): Now let’s look at a “less-tightly constrained” example. Let’s look at results for for the arbitrarily selected domain name

www.cs.uoregon.edu

for the last quarter. We’ll request any/all (non-DNSSEC) RRtypes across all bailiwicks for that domain. For ease of display, we’ve wrapped the results, just as we did in Example A:

$ dnsdbq -r www.cs.uoregon.edu -j -T datefix -A90d

{"count":8598,"time_first":"2010-08-14 05:11:07","time_last":"2021-11-30 02:26:39",

"rrname":"www.cs.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.4.25"]}

{"count":218670,"time_first":"2010-06-24 11:33:02","time_last":"2021-11-30 14:59:10",

"rrname":"www.cs.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"cs.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.4.25"]}

{"count":2492,"time_first":"2016-09-22 20:38:09","time_last":"2021-11-30 01:57:23",

"rrname":"www.cs.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"AAAA","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["2607:8400:205e:40::80df:419"]}

{"count":57021,"time_first":"2016-09-22 19:16:39","time_last":"2021-11-30 09:43:08",

"rrname":"www.cs.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"AAAA","bailiwick":"cs.uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["2607:8400:205e:40::80df:419"]}

Looking at those four records in JSON Lines format, we see that we’ve received:

- An “A” (e.g., name to IPv4 address) record from the

uoregon.edu

cs.uoregon.edu

- bailiwick

- An “AAAA” (e.g., name to IPv6 address) record seen from the

uoregon.edu

- bailiwick (“AAAA” records are RRtype code 28)

- An “AAAA” record from the

cs.uoregon.edu

- bailiwick

Those results all appeared in exactly the order we’ve described and expected to see.

Example C): Now let’s look at a still more complex example. Let’s look at all

*.uoregon.edu

domains as seen over the last 90 days. Because that’s likely to be a lot of data, we’ll save those results to a file for ease of review:

$ dnsdbq -r "*.uoregon.edu" -l0 -A90d -j -T datefix > uoregon.jsonl

$ wc -l uoregon.jsonl

20983 uoregon.jsonl

Since we can see that we have nearly 21,000 results from that query, to keep this writeup to reasonable length, we’ll just show selected “snippets” of those results. For example, starting with the top of that file, we see:

$ more uoregon.jsonl

{"count":472411,"time_first":"2019-02-22 01:10:03","time_last":"2021-11-30 19:55:15",

"rrname":"uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["184.171.111.233"]}

{"count":3396086,"time_first":"2020-01-29 22:16:36","time_last":"2021-11-30 20:12:37",

"rrname":"uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"NS","bailiwick":"edu.",

"rdata":["lsu-bdds1.lsu.edu.", "phloem.uoregon.edu.","ruminant.uoregon.edu.",

"ns1.f5cloudservices.com."]}

{"count":13074799,"time_first":"2020-01-29 22:17:41","time_last":"2021-11-30 20:35:19",

"rrname":"uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"NS","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["lsu-bdds1.lsu.edu.", "phloem.uoregon.edu.","ruminant.uoregon.edu.",

"ns1.f5cloudservices.com."]}

{"count":3705,"time_first":"2021-09-01 21:46:35","time_last":"2021-09-02 00:07:53",

"rrname":"uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"SOA","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["phloem.uoregon.edu. hostmaster.uoregon.edu. 2021090113 3600 1800 605000 600"]}

[...]

{"count":811398,"time_first":"2018-09-17 18:10:16","time_last":"2021-11-30 14:12:00",

"rrname":"uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"MX","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["10 mxa-000bfd01.gslb.pphosted.com.",

"10 mxb-000bfd01.gslb.pphosted.com."]}

{"count":14194,"time_first":"2021-03-15 19:42:26","time_last":"2021-11-30 09:19:17",

"rrname":"uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"TXT","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["\"v=spf1 mx ip4:128.223.0.0/16 ip4:163.41.128.0/17 ip4:184.171.0.0/17

ip6:2001:468:d00::/40 ip6:2607:8400:2802::/32 ip4:148.163.128.0/19

ip4:72.10.180.28/31 ?all\""]}

Those first six records shown above are all for just the raw delegation point (e.g., “uoregon.edu”). We see:

- The RRtype=”A” records are first, since “A” records have an RRtype code of 1.

- “NS” records for the raw delegation point come next, since “NS” records are RRtype 2.

- Within the NS category, the more general bailiwick (“edu”) appears first

- The more specific bailiwick (“uoregon.edu”) appears next

- The “SOA” records come after that, since “SOA” records are RRtype 6. (we’re just showing one of many SOA records in this snippet)

- Then we see an “MX” record, RRtype 15

- And finally, we see a “TXT” record, RRtype 16.

The next few records in the results look like:

{"count":51,"time_first":"2016-12-20 06:53:24","time_last":"2021-10-02 21:59:25",

"rrname":"windows-8.1.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.142.45"]}

{"count":543,"time_first":"2019-04-04 11:16:20","time_last":"2021-11-27 16:06:45",

"rrname":"m.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"CNAME","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["drupal-hosting-web-cluster5-prod.uoregon.edu."]}

{"count":48,"time_first":"2020-10-20 11:48:29","time_last":"2021-09-30 20:54:47",

"rrname":"dyn-128.223.65.70.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.65.70"]}

{"count":43,"time_first":"2020-11-05 23:18:22","time_last":"2021-11-24 18:18:10",

"rrname":"128.223.34.76.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.34.78"]}

{"count":55,"time_first":"2019-10-19 05:54:16","time_last":"2021-09-14 11:25:15",

"rrname":"dyn-128.223.65.78.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.65.78"]}

{"count":66,"time_first":"2019-10-09 06:03:15","time_last":"2021-09-30 20:55:41",

"rrname":"dyn-128.223.65.91.uoregon.edu.","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.65.91"]}

That may seem like a totally crazy order of presentation until you remember that we’re sorting the RRnames by reversed label order, and we pay attention to the length of each label.

That means that in this case, the as-reversed-by-label RRnames actually look like:

edu.uoregon.1.windows-8

edu.uoregon.m

edu.uoregon.70.65.223.dyn-128

edu.uoregon.76.34.223.128

edu.uoregon.78.65.223.dyn-128

edu.uoregon.91.65.223.dyn-128

The highlighted bits are indeed sorted in ascending order (and we need look no further than the (manually) highlighted label in each of those names to confirm those records are correctly sorted).

Before continuing to scrutinize those results, let’s rerun our query with our output RRnames reversed “automatically:”

$ dnsdbq -r "*.uoregon.edu" -l0 -A90d -j -T datefix,reverse,chomp > uoregon-reversed.jsonl

The highlighted options will ensure that:

- The date-times are display using normal “human” format (that’s the

datefix

- option)

- The RRnames are label reversed (so

www.example.com

- becomes

com.example.www

- ), and

- The “formal dot” (that’s normally shown at the end of each name) is elided thanks to the

chomp

- option.

When we run that dnsdbq command, some of the results in the output file look like:

{"count":46,"time_first":"2015-07-04 11:13:11","time_last":"2021-11-18 02:43:21",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ac","rrtype":"CNAME","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["lcb-web2c.uoregon.edu."]}

{"count":3935,"time_first":"2020-12-21 20:24:54","time_last":"2021-11-30 14:19:25",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ad.pki","rrtype":"CNAME","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["ad-sca.ad.uoregon.edu."]}

{"count":3769287,"time_first":"2014-05-30 06:42:49","time_last":"2021-11-30 09:05:33",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ad.ad-dc1","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.34.139"]}

{"count":35588723,"time_first":"2014-05-30 06:42:49","time_last":"2021-11-30 09:05:33",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ad.ad-dc2","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.34.134"]}

{"count":35588522,"time_first":"2014-05-30 06:42:49","time_last":"2021-11-30 09:05:33",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ad.ad-dc3","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.34.140"]}

{"count":35588176,"time_first":"2014-05-30 06:42:49","time_last":"2021-11-30 17:25:19",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ad.ad-dc4","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.34.135"]}

{"count":3266,"time_first":"2020-12-21 21:38:58","time_last":"2021-11-30 19:14:29",

"rrname":"edu.uoregon.ad.ad-kms","rrtype":"A","bailiwick":"uoregon.edu.",

"rdata":["128.223.162.89"]}

[etc]

You might briefly think “Uh oh, something must be wrong — what’s the reversed domain edu.uoregon.ad.pki doing ahead of the reversed domain edu.uoregon.ad.ad-dc1?”

Thinking carefully about this, remember that RRnames are sorted by label LENGTH, then by the values of the label. “pki” (at 3 characters) is shorter than “ad-dc1” (at 5 characters).

The “display-in-reversed-by-label” format output makes it clear that all is well in the default sequencing world for this modest-size dataset of nearly 21,000 results.

Example D:) What do we run into if we try doing something totally crazy, like trying to look at all

*.net

names for the last three days?

$ dnsdbq -r "*.net" -l0 -A3d -j -T datefix,reverse,chomp > net-reversed.jsonl

Database limit: Result limit reached

Hmm. Okay, there’s far more than a million results in *.net. That’s not really a surprise — https://www.verisign.com/en_US/channel-resources/domain-registry-products/zone-file/index.xhtml says that there are nearly 13.5 million dot net domains registered (to say nothing of all the combinations of FQDNs, RRtypes, bailiwicks and Rdata involving those domains that DNSDB tracks and reports).

Let’s ask for the three offset tranches we can get for this query, for an aggregate total of up to 4,000,000 results (though even that obviously isn’t going to get us through the total set of results that DNSDB has for

*.net

):

$ dnsdbq -r "*.net" -l0 -A3d -j -T datefix,reverse,chomp -O1000000 >> net-reversed.jsonl

Database limit: Result limit reached

$ dnsdbq -r "*.net" -l0 -A3d -j -T datefix,reverse,chomp -O2000000 >> net-reversed.jsonl

Database limit: Result limit reached

$ dnsdbq -r "*.net" -l0 -A3d -j -T datefix,reverse,chomp -O3000000 >> net-reversed.jsonl

Database limit: Result limit reached

$ wc -l net-reversed.jsonl

4000000 net-reversed.jsonl

Let’s check out what we’ve gotten in those four million results. What does the first observation look like (wrapped for display here)?

$ head -1 net-reversed.jsonl

{"count":212,"zone_time_first":"2019-11-11 15:52:29","zone_time_last":"2021-11-28 22:50:24",

"rrname":"net","rrtype":"NS","bailiwick":"net.",

"rdata":["a.gtld-servers.net.","b.gtld-servers.net.","c.gtld-servers.net.",

"d.gtld-servers.net.","e.gtld-servers.net.","f.gtld-servers.net.",

"g.gtld-servers.net.","h.gtld-servers.net.","i.gtld-servers.net.",

"j.gtld-servers.net.","k.gtld-servers.net.","l.gtld-servers.net.",

"m.gtld-servers.net."]}

That first observation is, as expected, Zone File data (rather than sensor data), and for the raw TLD name (e.g.,

net

) itself.

What about the last of those 4,000,000 results?

$ tail -1 net-reversed.jsonl

{"count":145,"zone_time_first":"2021-07-06 22:50:22","zone_time_last":"2021-11-28 22:50:24",

"rrname":"net.tzsws","rrtype":"NS","bailiwick":"net.",

"rdata":["v1s1.xundns.com.","v1s2.xundns.com."]}

At 4,000,000 observations for our

*.net

query, we’re STILL wading through Zone File data, and we’re only up to dot net 2nd-labels that are five characters long. We haven’t seen ANY sensor network data for dot net at all yet! This example perfectly illustrates:

- Why the impact of the default presentation order is important to understand

- Why you want to craft a carefully targeted query whenever possible, and

- Why users attempting to dump “entire TLDs” will find that isn’t very productive.

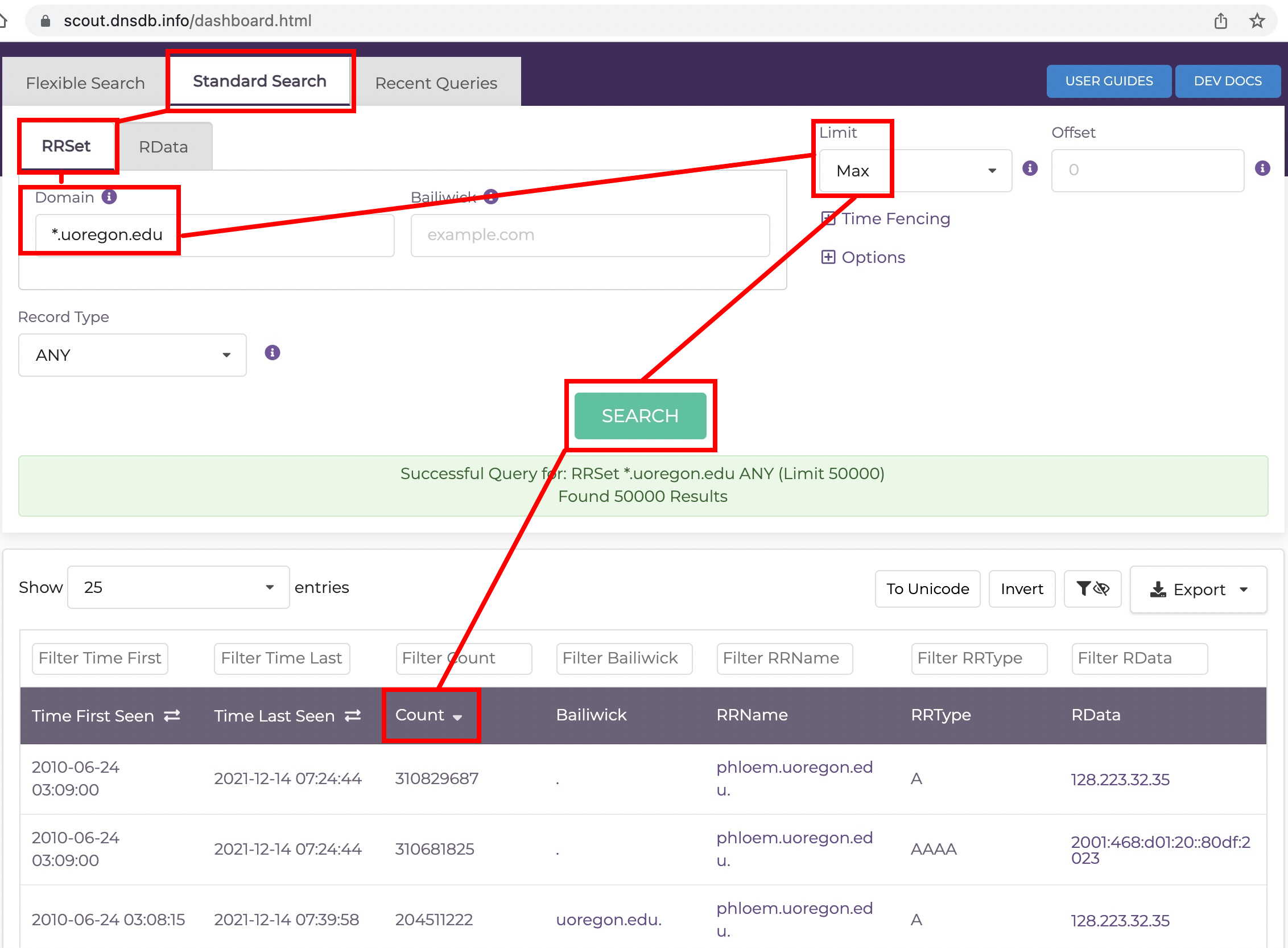

VII. Sorting Client Side in DNSDB Scout

While you don’t have the ability to preferentially sort and change the the subset of results you receive from DNSDB on the DNSDB server itself, you CAN sort the subset of results you’ve received “client side” (e.g., once the software client you’re using to access DNSDB has received those results).

Just for completeness, we’ll show you how to do this in two DNSDB clients: in DNSDB Scout (our GUI point and click web-based client), and in dnsdbq (our command line interface).

In DNSDB Scout, after you’ve run a sample search, simply click on a heading in the table of results to sort by that field.

For example, let’s sort the results for a

*.uoregon.edu

query by count, by clicking on the “Count” header row:

Want to see values in reverse order, instead? Click the same heading again. Want to sort by a different field? Just click that header.

VIII. Sorting Client Side in dnsdbq

If you’re using our command line client, dnsdbq, there are two sort-related command line options you need to be aware of — dash ess (with the ess either lower case or capitalized) and dash kay. Cutting and pasting from

$ man dnsdbq

we see:

-s sort output in ascending key order. Limits (if any) specified

by -l and -L will be applied before and after sorting,

respectively. In batch mode, the -f, -ff, and -ffm option sets

will cause each batch entry's result to be sorted independently,

whereas with -fm, all outputs will be combined before sorting.

This means with -fm there will be no output until after the

last batch entry has been processed, due to store and forward

by the sort process.

-S sort output in descending key order. See discussion for -s

above.

-k sort_keys

when sorting with -s or -S, selects one or more comma

separated sort keys, among "first", "last", "duration",

"count", "name", "type", and/or "data". The default order

is "first,last,duration,count,name,type,data" (if sorting is

requested.) Names are sorted right to left (by TLD then 2LD

etc). Data is sorted either by name if present, or else by

numeric value (e.g., for A and AAAA RRsets.) Several -k

options can be given after different -s and -S options, to

sort in ascending order for some keys, descending for others.

Replicating our DNSDB Scout sorting example in dnsdbq:

$ dnsdbq -r "*.uoregon.edu" -l0 -S -k count | more

;; record times: 2010-06-24 03:09:00 .. 2021-11-30 19:21:56 (~11y ~162d)

;; count: 309154620; bailiwick: .

phloem.uoregon.edu. A 128.223.32.35

;; record times: 2010-06-24 03:09:00 .. 2021-11-30 19:21:56 (~11y ~162d)

;; count: 309006772; bailiwick: .

phloem.uoregon.edu. AAAA 2001:468:d01:20::80df:2023

;; record times: 2010-06-24 03:08:15 .. 2021-11-30 19:33:08 (~11y ~162d)

;; count: 203840350; bailiwick: uoregon.edu.

phloem.uoregon.edu. A 128.223.32.35

;; record times: 2010-06-24 03:08:15 .. 2021-11-30 19:33:08 (~11y ~162d)

;; count: 203537192; bailiwick: uoregon.edu.

phloem.uoregon.edu. AAAA 2001:468:d01:20::80df:2023

;; record times: 2010-06-24 03:08:15 .. 2021-11-30 15:38:40 (~11y ~162d)

;; count: 109575370; bailiwick: edu.

phloem.uoregon.edu. AAAA 2001:468:d01:20::80df:2023

[etc]

IX. Some Common Misconceptions

Misconception #1: Sorting Results Client-Side Will Change the Set of Results You Get — FALSE.

The subset of results you receive (out of all total possible matching results) is determined on the DNSDB server. The DNSDB server always returns matching results in their natural order as previously described above.

AFTER those results get downloaded to whatever client you’re using (such as dnsdbq or DNSDB Scout or a DNSDB integration), the client may SORT (and thus change the order of your results as DISPLAYED), but this has NO IMPACT on the set of results RECEIVED from DNSDB.

Some modifications to your queries that WILL potentially change what the DNSDB server returns as results include:

- Making a more (or less) specific query (example: querying for

*.uoregon.edu

- vs.

*.cs.uoregon.edu

- vs

www.cs.uoregon.edu

- )

- Limiting results to just a specific RRtype (such as just “A” records)

- Specifying a bailiwick value

- Specifying a time fence

- Specifying a smaller (or larger) maximum number of results up to the lesser of [the maximum number of results requested by the user and allowed via their DNSDB client] and [the maximum number of results allowed per-query by the DNSDB server]

Misconception #2: You Can Specify Partial Label Wildcards (or Other Complex Pattern Searches) in DNSDB Standard Search to Narrow In On The Results Returned — FALSE.

When confronting a flood of DNSDB results, users may sometimes try to tweak their queries in ways that DNSDB Standard Search simply isn’t able to handle, such as attempting partial-label or mid-label wildcard searches.

By way of illustrating this, let’s consider some queries that are OK in DNSDB Standard Search:

Fully qualified domain names: www.example.com

Left hand wildcards: *.example.com

Right hand wildcards: example.*

Individual IPv4 addresses: 199.30.228.112

Individual IPv6 addresses: 2620:11c:f008::13

IPv4 CIDR network address blocks: 199.30.228.0/24

IPv6 CIDR network address blocks: 2620:11c:f008::/64

IPv4 address dashed ranges: 199.30.228.110-199.30.228.205

IPv6 address dashed ranges: 2620:11c:f008::5-2620:11c:f008::79

Now let’s consider some queries that are NOT OK in DNSDB Standard Search:

Double-sided wildcards: *example*

Mid-label wildcards: www.ex*ple.com

Partial-label wildcards: *ple.com

Wildcarded IP addresses: 128.223.32.*

Note that the above list is illustrative (and not an exhaustive list) of okay and problematic DNSDB Standard Search patterns (for example, we did not show raw hex queries).

If you’d like to find domain names that match “keywords” such as brand names (or domain names that match more complex patterns — up to and including regular expressions), try DNSDB Flexible Search. DNSDB Flexible Search can be an amazing “finding aid,” and it is bundled free with your DNSDB API or DNSDB Export subscription. For more details on getting started with Flexible Search, see the introductory DNSDB Flexible Search slide deck at https://www.domaintools.com/wp-content/uploads/DNSDB_Flexible_Search_Intro.pdf

Misconception #3: “I Can Ask for JUST Sensor Data from DNSDB API, Excluding Zone File Data” — FALSE.

DNSDB API Users: Unfortunately, you cannot currently say “Please exclude Zone File Data from my DNSDB API results.” If relevant Zone File results are available for a given DNSDB API query, you WILL receive them. Naturally, you can drop them once you receive them if you really don’t want them (e.g., for example by using grep -v), but you can’t exclude them a priori. (If this is functionality you think you might find useful, we’d love to hear from you about this.)

DNSDB Export Users: Bulk Zone File data cannot be provided to DNSDB Export customers, so Zone File data is always “automatically” excluded from searches made by DNSDB Export users (unless the DNSDB Export customer arranges with ICANN to directly download their own Zone File data, in which case we’re happy to help the DNSDB Export customer locally ingest that data).

**Misconception #4: If I Just Time Fenced My Request Sufficiently Aggressively, I Could Successfully Dump a Full Slice of a Big TLD (Such as Half-an-Hour’s Worth of .com or .net) — FALSE.

If you attempt this sort of strategy, your query will normally timeout/fail. For example, if you tried to dump half an hour’s worth of dot com, you might see:

$ dnsdbq -r "*.com" -A30m -l0 -j > star-dot-com.jsonl

dnsdbq: warning: libcurl failed with curl error 18 (Transferred a partial file)

Query response missing: Data transfer failed -- No SAF terminator at end of stream

If you’d like to learn more about SAF, Farsight’s Streaming API Framing Protocol, and how it helps to protect you from incomplete results, see https://www.domaintools.com/resources/user-guides/farsight-streaming-api-framing-protocol-documentation/

Misconception #5: There’s NO WAY To Dump All Matching Names for A Given Pattern from DNSDB (Even If You Have DNSDB Export) — FALSE.

DNSDB Export (aka “DNSDB On Premises”) is customarily described as “like DNSDB API, but running on local hardware.” It is accessed using a local copy of the same front end that normally handles DNSDB API queries run over the Internet, and behaves similarly — except for the fact it is running “on premises.”

That said, those who have purchased DNSDB Export can request permission from their account executive to directly access DNSDB MTBL files and do custom searches that exceed normal search parameters/normal search limits using

dnstable_lookup

and/or

dnstable_dump

.

X. Conclusion

We hope you now have at least a basic understanding for how results are ordered in DNSDB MTBL files, and how that ordering can impact the subset of results you receive out of the total set of results that may exist. You’ve seen some worked examples of how that ordering appears, and we’ve tackled what you can do “client side” with the results you receive. We’ve also tried to clear up some common misconceptions. We hope this discussion has helped to clarify why DNSDB results come out in the order they do, and why you get the results you get.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank (in alphabetical order) Ben April, Pawel Foremski, Chris Mikkelson, David Waitzman, and Stephen Watt for their review and extremely helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. Any remaining errors are solely the responsibility of the author.