IPv6 Deployment Over Time As Seen Through Farsight Security, Inc's Passive DNS Data

Introduction

The Internet we all know and love was built using traditional IPv4 addresses,“dotted quads” such as

104.244.13.104

.

Each address of that sort gets built from four eight bit bytes, resulting in a32-bit address. A 32-bit address space has the potential to yield2^32 = 4,294,967,296 IPv4 addresses, which naively sounds like rather a lot.Then again, the world’s a big place, many people use multiple devices today,and a variety of legacy issues, inefficiencies, and other technical realitiesmean that many of those ~4.3 billion theoretically-available IPv4 addresses arenot now, and never have been, actually available for use. The net result isthat like cold beer on a hot day at the lake, the world’s pool of IPv4addresses has quickly gotten drained.

The inadequacy of the IPv4 address space was recognized as long as twentyyears ago, see RFC175 (“Recommendation for the IP Next Generation Protocol”. Slow (but-steady) progress has been madeever since.

Please note the word “slow” in the preceding sentence: IPv6 deployment has notoccurred nearly as fast as had been hoped. This is a real problem given therate with which IPv4 addresses have been consumed. In fact, now that allregional IP registries (except AFRINIC) have exhausted their traditional IPv4free address pools, IPv4 addresses are becoming substantially more difficultto obtain.

Table 1: Free Pool Exhaust Date by Registry

|Registry|Region |Free Pool Exhaust Date|| -:| ——:||APNIC |Asia/Oceania |April 15, 2011 ||RIPE |Europe |September 14th, 2012 ||LACNIC |Latin America|June 10th, 2014 ||ARIN |North America|September 24th, 2015 ||AFRINIC |Africa |[not yet exhausted] |

Free pool exhaustion means that new ISPs (or other qualified parties needing“wholesale” quantities of IPv4 address space) now find themselves unable todirectly get that space from their regional registry.

All that qualified requesters are still able to get in the way of IPv4 addressspace is a meager one-time allocation of an IPv4 /22 (a single block of 1,024IPv4 address). That small tranche of IPv4 addresses is obviously not enough tosupport traditional IPv4 usage models where IPv4 address consumption scalesroughly linearly with their customer base. A single block of 1,024 IPv4addresses is really just enough for “transitional uses” (e.g., typically forInternet-facing load balancers in front of a farm of backend servers, or foruse in so-called “carrier-grade NAT” deployments).

Those who need more IPv4 addresses than they can get from their regionalregistry typically need to arrange for a third party to transfer IPv4 addressspace they no longer need. Those sort of “designated transfers” may involvepayment of a “fee” to the transferring party (although technically thetransferred IPv4 addresses are not being “sold.”) This can quickly becomeexpensive.

The alternative is IPv6. It offers abundant address space at negligible cost,and the time has come for sites to migrate from IPv4 to IPv6, or at least torun “dual-stack” with all hosts being connected via both IPv4 and IPv6.

Today’s Real Question

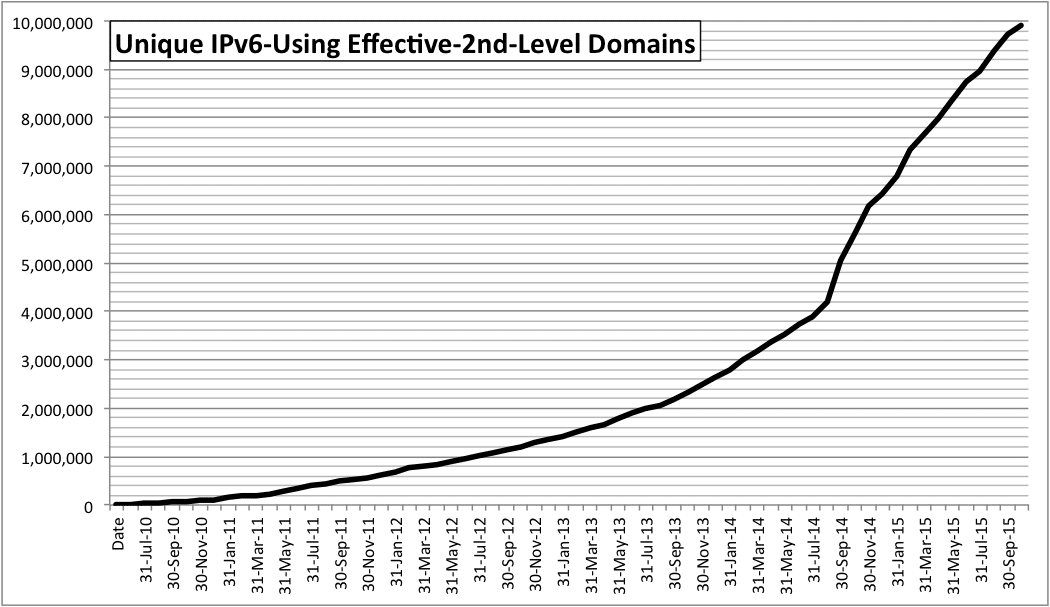

So how’s IPv6 integration coming? Are people embracing and deploying IPv6? Oris IPv6 still in the deployment “doldrums,” just limping along? Farsight Security, Inc.’s Passive DNSallows us to empirically answer that question. Looking month-by-month, let’stally the number of unique effective-2nd-level domains (“base domain names”) associated with one or more IPv6

AAAA

records.

We can then graph those values.

If IPv6 deployment is advancing nicely, we should see an accelerating rate ofdeployment over time. If IPv6 deployment is languishing, or proceeding slowly,that should also show up in the curve we see.

But how to mechanically get the data we need? When approaching a study of thissort, the first thought is that this sort of scenario might be a perfectcandidate for using the Farsight

dnsdb_query

command line tool, simplyselecting all quad A records for dot com or some other top level domain (TLD)of interest, adjusting time fencing values for each month. In fact, however,that sort of “brute force” approach might miss important pockets of IPv6deployment in other TLDs, is inefficient, and is subject to a hard cap of amillion returned records. For all these reasons and more, that approach likelyjust wouldn’t work very well for this purpose.

Fortunately, there’s an alternative. In addition to making passive DNS dataavailable via our DNSDB API web interface and via ourcommand-line interface/API, Farsight Security also sells raw passive DNS datain MTBL format as “DNSDB Export.” DNSDBExport is Farsight’s premium product, and makes it possible for you to arrangeto receive an “on-premises” copy of the entire Farsight Passive DNS database.At that point you can run complex local queries against that database,including queries like the ones needed to answer the question at hand in thiscase.

Our Engineering team members provided invaluable support for this research.Farsight Engineer H.S. took a list of IPv6 prefixes we supplied from IANA, and then extracted all

AAAA

(IPv6 address) recordspresent in the DNSDB Export files. We then processed those records to extractall unique effective 2nd-level domains, constraining the data by use of amoving monthly “time horizon.” (The scripts we used to run those analysesappear at the end of this article). The resulting data looks as follows…

Illustration 1. IPv6 Deployment, as measured by IPv6-using uniqueeffective-2nd-level domains

Looking at that graph, we can see that while it starts very close to the originin June 2010, by the end of November 2015, we’re up to nearly ten millionunique effective-2nd-level domains that use IPv6. That’s commendable progress,although we still obviously have a lot of work still to do.

Conclusion

If you’ve been reluctant to embark on deployment of IPv6 in your owninfrastructure, perhaps assuming that IPv4 address space will remain cheap andrelatively easily available forever, that fantasy has come to an end (unlessyou’re based in Africa — AFRINIC does still have some IPv4 address space leftfor qualified AFRINIC-region requesters).

If you’re not in Africa and need material amounts of IPv4 address space thesedays, you’re probably going to need to arrange for a designated transfer froma third party, and that likely won’t be cheap.

The rest of the world (e.g., everyone except those in the AFRINIC region)really needs to be moving expeditiously towards deploying IPv6, as FarsightSecurity, Inc., itself has.

Nearly ten million domains have already made the IPv6 plunge. These days, IPv6largely just works. Isn’t it time for you and your company to deploy IPv6,too, assuming you haven’t done so already?

Finally, if you have a need for in-depth historical data for DNS analyses,nothing beats Farsight Security, Inc.’s DNSDB Export as a source of data forcustom DNS data mining.

Joe St Sauver, Ph.D. is a Scientist with Farsight Security, Inc.

Appendix: The Simple Scripts Used To Generate The Data Used In This Article

proc-v6.sh

#!/bin/bash

## data files are assumed to be in prefix-*.json

## jq15 is version 1.5 of jq, see https://stedolan.github.io/jq/

YEAR=2010

MONTH=0

while [ $YEAR -lt 2016 ]; do

while [ $MONTH -lt 12 ]; do

myunixtime=$(echo "[$YEAR, $MONTH, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]" | jq15 'mktime')

echo $myunixtime

filename=$myunixtime.hostnames

filename2=$myunixtime.domains

summary=$myunixtime.hostnamecount

summary2=$myunixtime.domaincount

cat prefix-*.json | jq15 -r -f print-ipv6-matches.jq --arg cutoff \

$myunixtime | tr -d '"' | sort | uniq > $filename

wc -l $filename > $summary

2nd-level-dom < $filename | sort | uniq > $filename2

wc -l $filename2 > $summary2

MONTH=$((MONTH+1))

done

MONTH=0

YEAR=$((YEAR+1))

done

print-ipv6-matches.jq

if (.time_first < ($cutoff|tonumber))

then (.rrname)

else empty end

2nd-level-dom.pl

#!/usr/bin/perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use IO::Socket::SSL::PublicSuffix;

my $pslfile = 'public_suffix_list.dat';

my $ps = IO::Socket::SSL::PublicSuffix->from_file($pslfile);

my $line;

foreach $line (<>) {

chomp($line);

my $root_domain = $ps->public_suffix($line,1);

printf( "%s\n", $root_domain );

}