Less Phishing, More Cat Pictures

Phishing—a scourge of the modern Internet. We endure it so that we have all of the other benefits of being online, such as connecting with family and friends, accelerating business, and, of course, viewing cute cat pictures.

Being forewarned is being forearmed. In this post for CISA’s Cybersecurity Awareness Month, we will review what phishing is as well as the underlying issue of social engineering, complete with additional examples throughout history. We will conclude with ways you and your organization can stay safe out there.

Phishing Defined

Phishing can be defined as “the fraudulent practice of sending messages over the Internet purporting to be from known, reputable companies or organizations in order to induce individuals to reveal private personal, organizational, or financial information.” This can include revealing passwords, physical addresses, and credit card numbers. Historically, phishers did this for immediate financial gain by draining your bank accounts. Now, phishers have options and may instead sell your information to other bad actors for a variety of purposes.

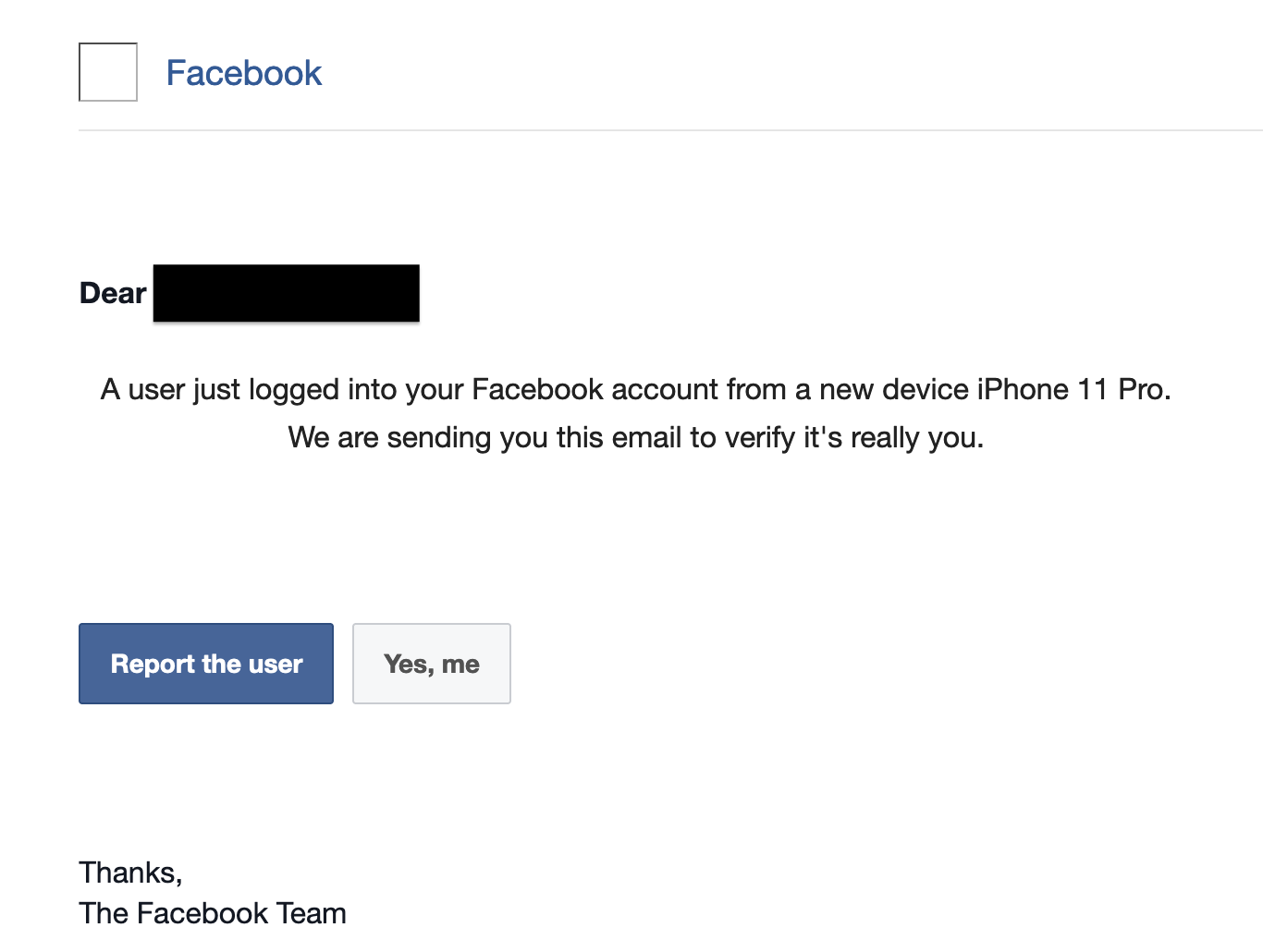

Let’s look at a few examples of phishing in some more detail. Figure 1 is an email from Meta claiming someone unknown logged into the target’s Facebook account. Here, the bad actors want access to Facebook to tap into the target’s social network to facilitate scams.

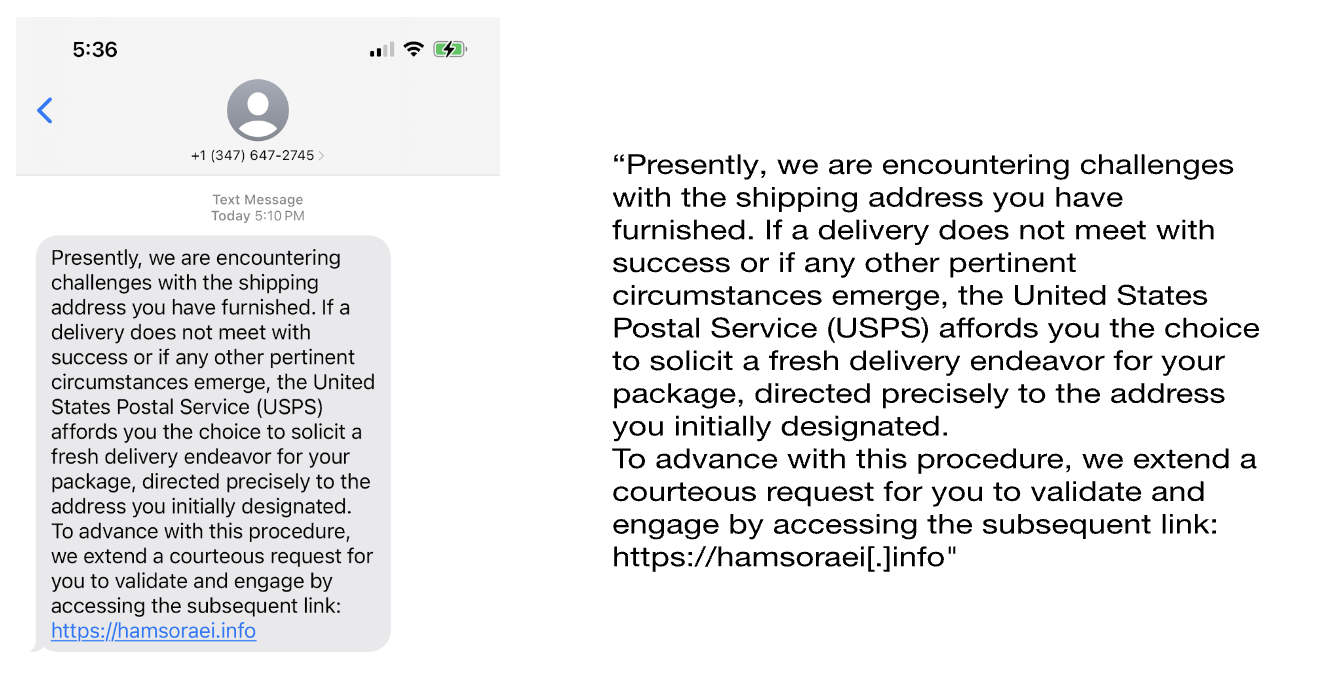

Second, here is a ‘smishing’ message, a phish attempt sent over text messaging claiming to be from the USPS (Figure 2). Smishing as a term being the combination of SMS and phishing. The URL eventually redirects to a website looking to “reconfirm” the target’s name and physical address. DomainTools Research dug into this scam in a recent blog post.

Figure 3 is a blurred screenshot from TikTok claiming to advertise financial advisor services. Again, DomainTools Research dug deeply into this in early 2023. In this scam, the bad actors convince the target to invest in cryptocurrency, stealing the target’s money and private financial information. Known as “pig butchering,” this scam works by building rapport and trust with the target over time before convincing them to invest with the bad actors.

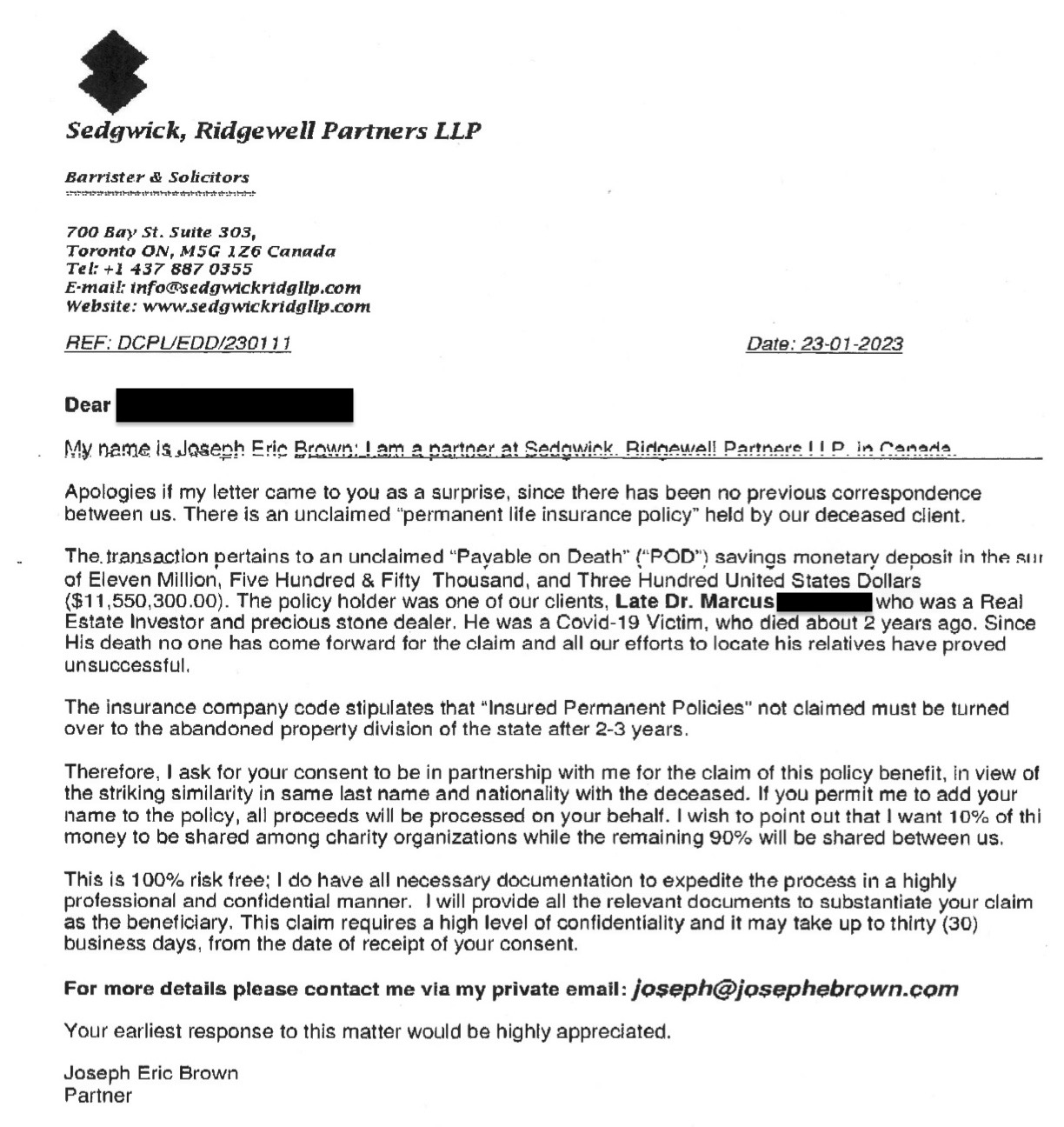

Finally, here is an example where the bad actors, posing as attorneys, are attempting to convince the target that their client, a “Real Estate investor and precious stone dealer” died from COVID-19 and that his fortune is unclaimed, Figure 4. This is commonly known as an “advance-fee scam” or “419 scam” where a target pays some fee upfront in anticipation of a larger payout later which never comes. A tactic in this scam is to keep the user paying additional small fees over time (e.g. “local tax authority fee,” “wire transfer registration fee”) to keep the target engaged and fleece them out of more money.

In all of these scenarios, a bad actor is leveraging the Internet to convince the target to provide login credentials or financial information.

Social Engineering

Phishing is the most prevalent example today of social engineering, defined by NIST as “the act of deceiving an individual into revealing sensitive information, obtaining unauthorized access, or committing fraud by associating with the individual to gain confidence and trust.” [NIST]

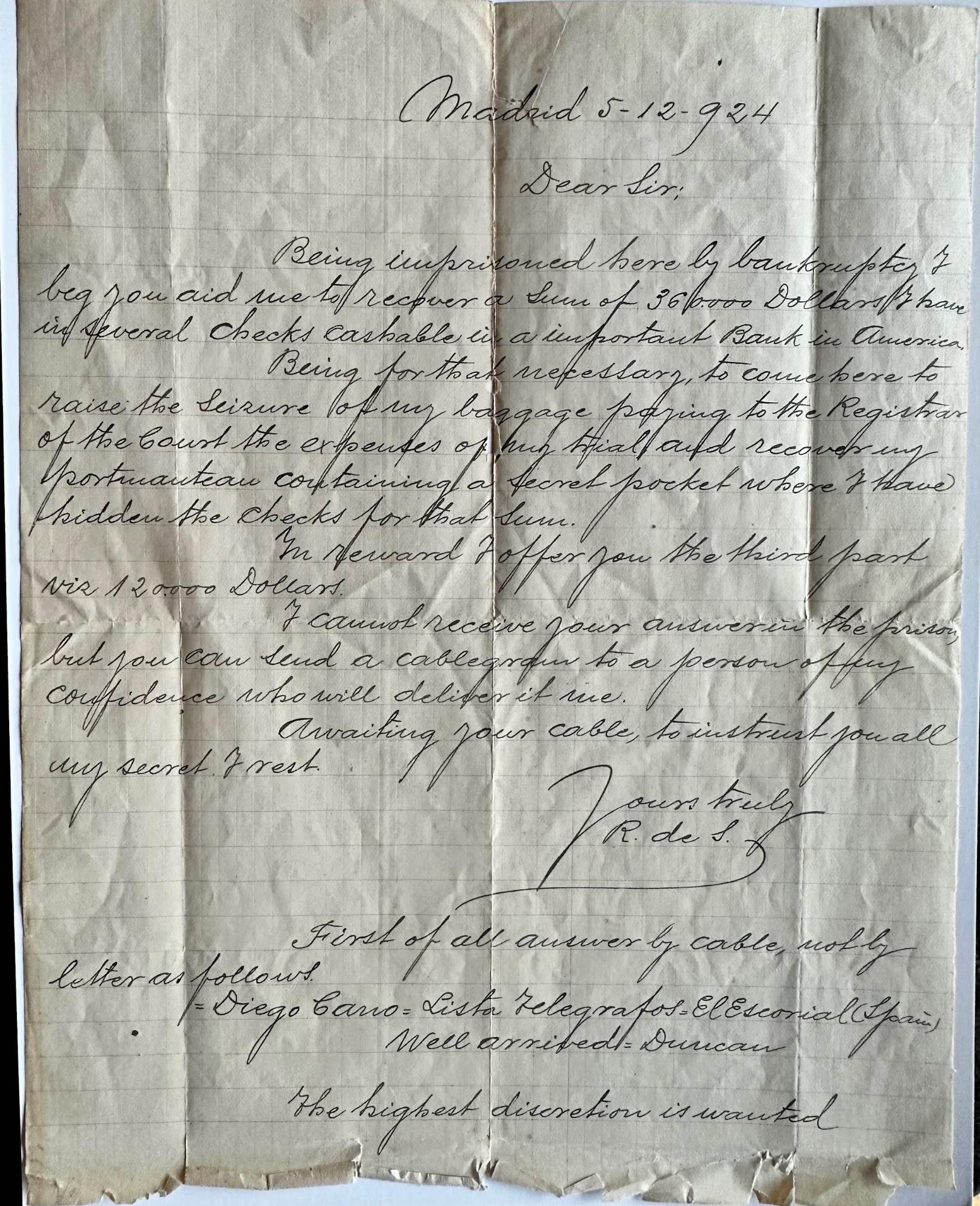

People have been trying to deceive others for a very long time—caveat emptor! Indeed, we have an example here of an original Spanish Debtors Prison letter, one of the original “advance-fee” scams (Figure 5). This one dates back to 1924. It was sent by mail and required the target to respond by cable, by sending a telegram! How can a prisoner receive it? The checks are hidden in a “secret pocket.” It’s also worth noting that, “The highest discretion is wanted.”

There are many reasons why people are susceptible to such social engineering scams. A key set of factors are not technical but rather psychological, including:

Trust and Authority: People may trust individuals or entities they perceive as authoritative or legitimate. Phishers can impersonate these trusted sources, such as well-known brands (Figure 1), government agencies (Figure 2), or financial institutions (Figure 3). If an interaction claims to be from such an entity, individuals may lower their guard.

Urgency and Fear: Social engineers may use fear and urgency as tools to manipulate victims. As demonstrated in Figure 1, a phishing email may claim that your account is compromised and needs immediate attention. Under emotional stress, a targeted individual could make hasty decisions without critically evaluating the situation.

Curiosity and Temptation: Many scams entice individuals with promises of something exciting, like a cash payout (Figures 4 and 5) or accessing exclusive content or private information. This taps into the psychological principle of curiosity, as well as a possible “fear of missing out” (FOMO).

Reciprocity: People have a tendency to reciprocate when someone does something for them. Phishers may initiate an interaction by offering something small, like a free e-book or trial, creating a sense of obligation in the recipient to respond. The scam highlighted in Figure 3 starts with a promise of financial advice before moving on to the scam. The “advance-fee” scams operate in reverse where the victim becomes invested in the scam due to an upfront payment.

Social Proof: People often look to others for guidance on how to behave, especially in uncertain situations. Phishing scams might create a false sense of consensus by using statements like “Hundreds have already benefited from this offer” to make the victim feel like they should join in. The scam highlighted in Figure 3 had domains for their fake financial advisors containing such statements.

Information Overload: People receive a vast amount of information daily. This overload can lead to people to take cognitive shortcuts, making them more susceptible to overlooking red flags or critical details in any one interaction. Note the sheer number and variety of examples in this post.

How Can You Protect Yourself Against Phishing?

There are several different things that you and your organization can do to help protect yourselves from phishing. Some are social checks and process improvements and others are technical improvements.

Be wary of what you don’t expect online. This could also be phrased as having “virtual stranger danger.” Only you know what your typical online interactions look like, so when you see something odd, spend an extra few minutes understanding what it is.

- Look out for unsolicited emails, messages, or phone calls, especially if they request sensitive information or immediate action. Phishing messages can create a sense of urgency or fear to pressure recipients into quick responses.

- Poor language, spelling errors, and grammatical mistakes are common in phishing attacks. Legitimate organizations typically maintain high-quality communication.

- If an offer seems too good to be true, it most likely is. Scammers use enticing offers to lure victims.

- Ask someone else for their opinions on a specific email or interaction. Sometimes a second review on a suspicious interaction can help you see the scam for what it is.

Prepare your accounts and establish processes. This may seem like extra work up front, but it is the ‘workhorse’ effort that will keep your online accounts safe from phishers and other bad actors.

- Create strong, unique passwords for each of your accounts online. That way, if a scammer gets into one of your accounts they cannot reuse your password to get anywhere else.

- Use multifactor authentication (MFA) for your accounts online, especially accounts with sensitive personal information such as your finances or email. Never give your MFA code to anyone who asks for it, only to the service webpage you are actively logging into.

- If you’re part of a critical business process, such as approving wire transfers, establish a secondary out-of-band process to validate these transactions. If you are in the same physical office, for example, agree to talk to the other approver face-to-face. If you’re remote, create a second communications channel, like text messaging, phone calls, or Slack, for approvals.

Invest in tooling. Phishing is enabled because the Internet has made it easier to connect. This delivery mechanism can also work to your advantage by scanning messages automatically.

- Ensure your computer, phones, and other Internet connected devices are fully patched and up-to-date.

- Look for mismatched domain names and URLs in the email or message. Often phishers will use ‘look-alike’ domains that resemble legitimate websites but have small discrepancies. If you don’t recognize every character in that domain as belonging to a domain name you trust, don’t trust the message.

- Understand how your email’s spam and phishing detection works, and what to look for if your email provider flags something suspicious.

- If you’re part of a larger organization, consider investing in protective phishing detection and/or threat intelligence solutions to identify threats or remediate events faster.

Conclusion

Phishing is really just social engineering executed via the Internet. The methods are the same: appealing to trust, creating a sense of urgency, establishing social proof—all to get your private information and use it to malicious ends.

As shown in the examples in this piece, there are a wide variety of ways that phishers can attempt to contact you. There are many things you and your organization can do: be wary of unsolicited messages you receive, prepare your accounts and establish critical processes, and invest in your hardware and online tooling.

With that, we hope you can get back what’s really important: connecting with others, creating meaningful work, and, of course, enjoying cat pictures!

PS. For those who believe that the Internet was made for cat pictures, we recommend the Hugo Award-winning short story, “Cat Pictures Please.”