Valuable Datasets to Analyze Network Infrastructure | Part 1

Depending on your interest in certain subjects, feel free to jump ahead:

What is the Domain Name System (DNS)?

Leveraging DNS For Investigations in Your Environment

Introduction

On a typical morning you might be sipping on tea or coffee when you receive an urgent email from your finance team. They received a strange request from the CFO for a prompt payment of funds, and you suspect a business email compromise. Right after your post-lunch food coma kicks in, you are tasked with incident response on something your endpoint detection picked up on, so you quickly pull the endpoint in to do some analysis. And finally, as you are about to shut your laptop for the day, you hear from a concerned manager regarding your organization’s owned infrastructure. Is there an exhaustive list of domains owned by your organization? Is this obscure domain just something marketing forgot to share with your team? Or is an attacker looking to target your organization? In order to take appropriate action on the following scenarios and finish out your day at a reasonable hour, one question you’ll likely ask yourself is “what datasets do I have at my disposal to gain additional insight and context to resolve these scenarios?”

The purpose of this blog series is to highlight a number of datasets proven by experienced IR teams to be valuable when analyzing network infrastructure. Throughout this series, I’ll provide some context as to why the datasets exist, how they interact with your own internal threat intelligence, and their key strengths and limitations. I feel a bit like a Southwest Airlines flight attendant when I say “we know you have many choices when it comes to selecting your threat intelligence, and we thank you for choosing [enter dataset here] for your investigations!”, but in reality, many folks like yourself are juggling a multitude of internal and external intel, so I hope this blog highlights some tools that exist in your proverbial toolbox, and can help identify when they are valuable to pull off your “threat intelligence pegboard.” This way when you look at the aforementioned scenarios, you have confidence that you didn’t miss the signal.

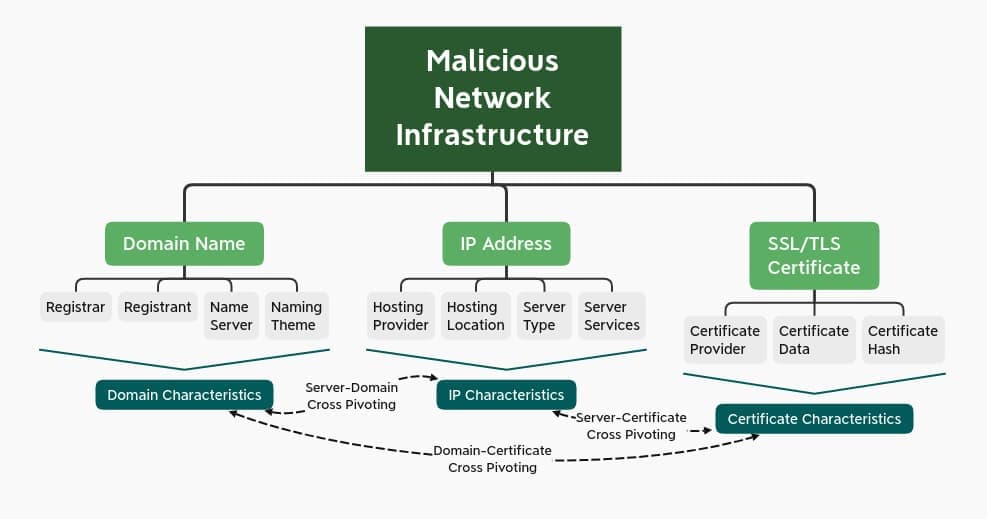

In this blog, I’ll be focusing on the Domain Name System (DNS). To name a few of its components, you have IP addresses, nameserver hostnames and IP information, Start of Authority (SOA) records, and Top Level Domains (TLDs). Looking at these types of data in a vacuum is nowhere near as valuable as understanding their relationships to one another (and other datasets), so I would be remiss if I didn’t remind you to read Joe Slowik’s masterpiece “Analyzing Network Infrastructure as Composite Objects,” where he illustrates how to analyze network observables according to their relationships and patterns of composition, which in turn yields insights into adversary behaviors, enriching the value of the network indicator.

Credit: Joe Slowik

What is the Domain Name System (DNS)?

As one can imagine, DNS is our cup of tea here at DomainTools. For a short period of time, we joked internally about starting a series called “Drunk DNS” (a clever parody of the History Channel’s Drunk History). Of course, DNS is both celebrated and cursed throughout the security industry (depending on the day). The late Dan Kaminsky, who discovered a fundamental flaw in DNS back in 2008 declared “it’s always DNS”. A similar sentiment is shared in a popular haiku.

DNS is quite robust and vast and as a result many folks portray its complexities as security shortcomings. While it’s true that it can be abused and create security risks, the richness of DNS also makes it a treasure trove of information, and as an industry we are only scratching the surface by taking advantage of a small number of DNS records. But to set the stage, let’s begin with why DNS exists and how it operates.

The History of DNS

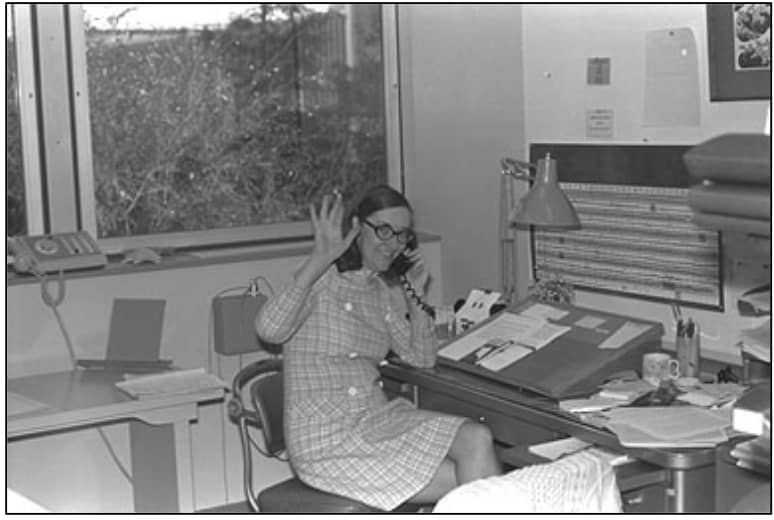

The process of DNS, which I’ll explain here in a moment, dates back to the days of ARPANET. SRI International (known previously as The Stanford Research Institute) maintained a text file referred to as HOSTS.TXT that mapped host names to the numerical addresses of computers on the ARPANET. This process was developed by American information scientist, Elizabeth Feinler. These addresses were assigned manually. You could call into the SRI’s Network Information Center (NIC) and they would grab a computer’s hostname and address and add them to the primary file.

Elizabeth Feinler, Credit: The New-York HIstorical Society Museum & Library

As one can imagine, this manual process to maintain a centralized host table quickly became too cumbersome. By the early 80’s, an automated approach to the naming system was needed. As a result the Domain Name System (DNS) was created in 1983. The IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) published the original DNS specifications in RFC 882 and RFC 883. DNS was followed by UC Berkeley students writing the first UNIX server for the Berkeley Internet Name Domain (known to many as BIND). (If this topic interests you, I’d highly recommend tuning into our podcast with Paul Vixie, who maintained BIND starting in 1985 before it was ported to the Windows NT platform.)

How DNS Works

All devices on the Information Superhighway (whether it be your smartphone, laptop, etc) communicate amongst themselves using numbers known to us humanoids as “IP addresses”. This description always reminds me of the episode of the Office where Dwight finds himself in an epic sales duel with the online Dunder Mifflin store and yells “I assume you read binary, so why don’t you 011 1111 011 011!”. There is a delightful Reddit thread on this altercation if you’re interested.

Credit: The Office, NBC Universal

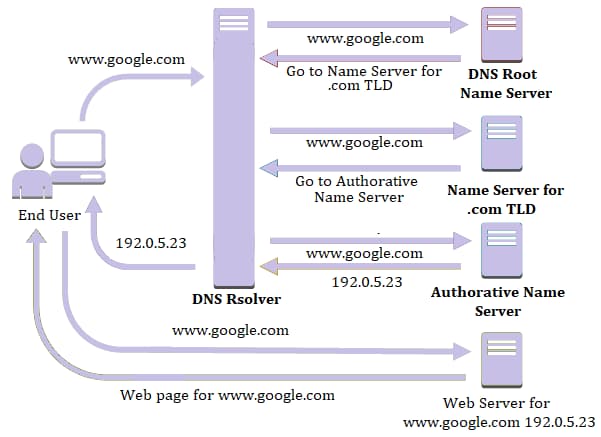

My sincere apologies for the tangent, now where were we? Ah yes, IP addresses. One of the reasons DNS exists is because it’s awfully difficult to remember 174.35.6.21 in order to enjoy The Onion’s brilliant use of satire (if only they had a special router for that?). Instead, the following process happens behind the scenes, which is known as a recursive lookup. Below is a list of steps in this process:

- You type theonion.com into your browser. Your browser then sends a query to find the corresponding IP address.

- The first stop for this query is the recursive DNS resolver. There are thousands of recursive DNS resolvers, and they can be operated by your Internet Service Provider (ISP), a third party, or wireless provider. The recursive DNS resolver knows which other DNS servers can help answer the question “what is the IP address of theonion.com?”. The recursive DNS resolver cannot answer this question, unless the same question has been asked and answered, the response will be cached for future forward lookups.

- Therefore, the recursive resolver will ask the root DNS server to answer the same question (what is the IP address of theonion.com). There are 13 root DNS servers that exist across the globe. To help answer the question, the root DNS server starts at the far right of the domain you are looking up, known as the top level domain (TLD). In our example, the TLD is .com.

- At this point, the query is referred to the TLD nameserver. These servers store information for the second level domain (for our example that would be “theonion”).

- This lands us at the domain’s authoritative nameserver, which returns the IP address for the full domain to the recursive DNS resolver.

- At this point, the recursive DNS resolver tells the browser the answer to our question; 174.35.64.21. Now your browser can grab the website’s content and voilà! You’re enjoying delicious satire.

Credit: Quest10

This is all happening in the blink of an eye, and through this process, you can pull apart many interesting artifacts to inform your investigation. We’ll talk through these individual aspects in this next section.

For one-off DNS lookups, your command line/terminal can be a useful tool. Here is a quick guide on terminal lookups (note that this article incorrectly implies that reverse lookups can show all domains on an IP, but otherwise appears accurate) and command line prompts.

Valuable Artifacts From DNS

There is a lot of value in DNS that are oftentimes forgotten or overlooked, so what are indicators that should capture your attention? In this next section, I’ll walk through key elements of DNS and include a list of interesting signals when leveraging this dataset.

Internet Protocol (IP)

The tried and true analogy for DNS is the good ole yellow pages. The domain name is the name of the individual you’re looking for, and the IP is their phone number. I covered this process above.

A familiar adage in security surrounding IP addresses is “rent an IP, buy a domain,” meaning threat actors have the ability to move around their infrastructure at will, making IPs more ephemeral than their “phonebook” counterpart, the domain. Regardless, looking at IPs can provide some critical information.

- Rapidly changing IP addresses can be an indication of the fast flux DNS technique employed by threat actors. Fast flux is executed by having many IP addresses associated with a fully qualified domain name (FQDN). IP addresses are swapped out at a high frequency through changing DNS records. This way, botnets are able to hide phishing and malware websites they stand up. Actors also use fast flux techniques to cycle through their c2 infrastructure.

- Number of Domains hosted on a single IP can help you discern if someone stood up their own infrastructure, or used a hosting provider (like a GoDaddy). Pivoting and expanding on a low number (a few hundred or less) domains with a shared IP address can provide you with some level of intent. As an example, when you see consistent naming, especially when combined with relatively low populations, then it’s far more likely that the domains are a meaningful cluster, i.e. they are related. The sophistication may or may not be high, but you have a good piece of forensic metadata (meta-metadata?) in identifying that cluster. If, however, you notice there are 100,000 or so domains on an IP address, this would indicate commodity hosting infrastructure. This doesn’t necessarily prove the relative badness of the domain. It is, however, useful for filtering out indicators that you can ignore because it won’t really add any meaningful information to an investigation.

Nameserver

Nameservers are a critical part of DNS, a pillar of a piece of infrastructure’s foundation. For the sake of clarity, I’ll be referring to the authoritative nameserver (rather than the nameserver for the TLD). Here are some things to look for.

- Bulletproof hosting, or providers with a reputation for refusing to take down a malicious domain, is also cause for concern. I would love to include a list of these organizations, but unfortunately they are constantly shifting. If you’re curious about bulletproof hosting, I’d recommend reading Brian Krebs’ in-depth article.

- Number of domains pointing to a nameserver or nameserver IP, similar to my description above with IP addresses, can be a quick indicator of whether or not someone stood up their own infrastructure.

- Sinkholed nameservers: if a domain has been sinkholed, that domain’s NS record will point to a nameserver owned by those operating the sinkhole. Nameservers with a wide array of known malicious domains for malware families often give away a sinkhole if it isn’t listed publicly. Unfortunately there isn’t one central list of sinkholers, so you have to use your best judgment and corroborating research to determine whether they are looking at a sinkhole. Microsoft’s sinkhole events report is a recommended resource.

- Number of nameservers for a domain: typically legitimate domains have multiple nameservers (i.e ns1.costco.com, ns2.costco.com, ns3.costco.com). Oftentimes malicious infrastructure only has one nameserver (i.e ns1[.]castco[.]com). Additionally, if the domain has multiple nameservers, it can be useful to see if there are multiple IP addresses or if they are all hosted on the same IP. This is not proof of maliciousness, but it may be a good signal to continue your investigation.

- Nameserver hosting, for example, changes in nameservers from a default hosting nameserver to a unique, or “boutique” value can be an indication that someone is running their own nameservers. Hostnames for popular hosting providers are listed below for your quick reference. Most companies now use hosted nameserver providers so it can often be an indication of an adversary-controlled domain that a NS points to the same domain and at the very least an indication that it’s a smaller, owner-managed operation. This could indicate things like DNS tunneling or command and control.

Hosting providers and their nameserver naming conventions

Start of Authority Record (SOA)

Start of authority records define administrative information at the DNS zone level, and they are required for domains. Very often, however, the SOA values are just left at the defaults given by the hoster/registrar. Simply put, the analyst is looking for a non-default, unique email address in the SOA data. SOA records typically include fields called MNAME, RNAME, serial, Refresh, Retry, Expire and time to live (TTL). I won’t describe each of these elements, but if you’re interested, read more on them here.

- RNAME is an extremely important field included in SOA records. This is the email address of the admin who is responsible for the zone. In a post-GDPR world, these email addresses, which aren’t redacted in SOA records, can be uniquely shared attributes that help correlate campaigns and activities. You might also find an administrative email for the nameserver hosting provider, which is not as valuable. Inclusion of RNAMEs in SOA records aren’t terribly common, but they are great low hanging fruit. And hey, sometimes threat actors make simple opsec mistakes!

- Length of TTL can be a signal of techniques used by bad actors. A short TTL (a second or two) means DNS will continue doing lookups because actors are moving infrastructure around to make it more difficult for vendors and defenders to catch them. Short TTLs aren’t always an indication of badness. They are also commonly used in content delivery networks (CDNs) for less sinister purposes.

Mail Exchange/Exchanger (MX) Record

The mail exchange record points email to a mail server. It describes how email messages should be routed in conformity with the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP). The MX record must point to another domain. MX records also include a priority which stipulates preference (the higher the number, the higher the priority).

- An MX record for a mail server on the same domain, much like with nameservers, indicates an owner-managed setup. In the case that this is coupled with mail server validation like sender protection framework (SPF) records it can be a sign that an attacker is trying to make their mail look legitimate to pass through mail servers while phishing.

- Non Standard MX records, meaning MX records that aren’t stood up by the hosting company of the IP/nameserver are an interesting signal. This could mean they are operating their own email server locally, therefore it is easier to monitor their activity and profile their behaviors.

- Number of MX servers on a domain: the same rules apply for MX servers and nameservers. The number of MX servers on a domain can be a good indicator as to whether or not something is legitimate. If a domain has two or so MX servers, this is pretty typical for valid domains. But, if there is only one MX server, or a mismatch of where those MX servers are hosted, this is cause for concern.

- MX record name: an “odd” MX record, especially if the MX server name closely matches the semantic structure of the domain name itself, is a good indicator of badness. If you see a bunch of domains with a common naming pattern like “{10,11,12,13,14…}sharepoint-login[.]com” it is likely these are phishing domains. Similarly, when seeing a bunch of domains with keyboard-smash names like “k23j23jklkjlkj32l[.]com” on the same IP, one might assume they are associated with spam infrastructure.

Top Level Domain (TLD)

Per the earlier description of how DNS functions, the top level domain is at the second highest level in the hierarchy after the root. As of June 2020, there are over 1,500 TLDs. The number of TLDs has exploded in recent years, now that any established public or private organization can apply to create a generic top level domain (gTLD). This increases the surface area for attackers to take advantage of lookalike domains to target organizations or leverage trusted brands to maximize credibility.

- If the TLD is uncommon (common TLDs include .com, .net, .org, .edu, or relevant country code TLD (ccTLD)), this is a signal. Some TLDs with higher concentration of malicious domains include .top, .cyou, tk, and .ml.

Leveraging DNS For Investigations in Your Environment

The list above should be a great starting point for taking advantage of DNS. No useful investigation or analysis happens in a vacuum with a single dataset, so below I’ll highlight complementary data that pairs with DNS, ways to automate this approach, and finally what action to take when your investigation or analysis are complete.

What Pairs Well with DNS?

- Associated scraped (live and cached) websites, names, documents, social networks (backlinks), any hidden pages, and usernames (handles)

- Passive DNS (pDNS)

- Site tracking codes (i.e Google Analytics)

- Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/ Transport Layer Security (TLS) certificates

- Whois for Domains and IP address blocks

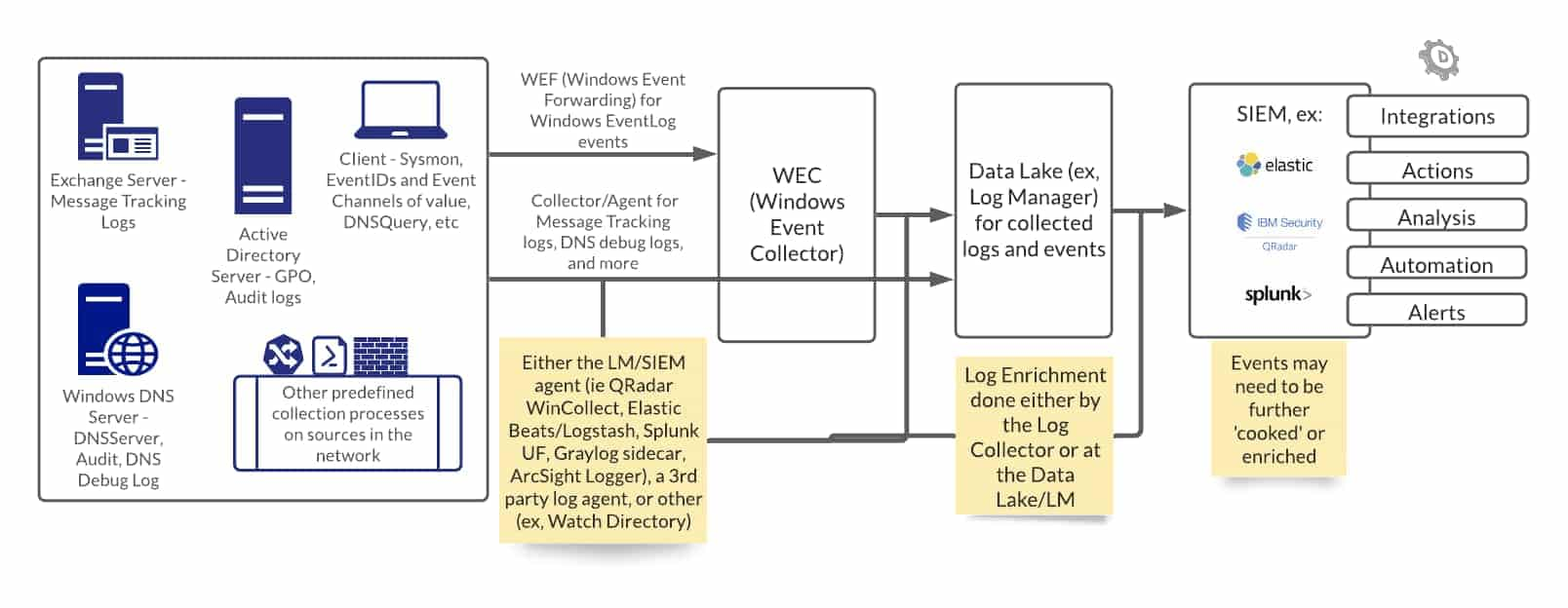

Automation and Orchestration

In order to clear room in your day for solving more complex problems, automation is key. Whenever possible, taking a series of manual tasks and turning them into security automation orchestration response (SOAR) playbooks is recommended.

Here is an example pulled from Tim Helming’s blog, Streamlining Adversary Infrastructure Hunting With SOAR:

- Aggregate all log sources that have domain names available (more on this later)

- Normalize the logs and extract the domain names (at the SLD level, e.g. “example.com”)

- Write these to a file

- Look up all domains against the one of these four data sets

- Discard domains in the Top Million

- Write remaining domains to a “candidate domains” file

This would give you a list of domains that aren’t among the Internet’s most common. It would by and large select-in most young domains, since young domains are less likely to make the top million than older ones. Likewise, it will tend to select-in domains of higher risk, because malicious domains tend to be flagged and placed on block lists before they reach the top million. Of course, there are exceptions to these, but it’s a first-stage filter that many SOCs like to use. To put SOAR in context, the diagram below illustrates the workflow of logs from endpoints to further action.

Next Steps

Identifying DNS data that requires further investigation is the beginning. Enriching indicators from your endpoint with DNS data and many other types of data (ideally through an automated process) can help answer the question “is this bad” and be used to expose larger campaigns.

Conclusion

Lists of interesting signals in DNS above are far from exhaustive. I hope they are useful in making quick determinations throughout your investigations. Making yourself the authority on DNS (pun intended) has its benefits. While DNS wasn’t built as a security forensics tool, it contains a lot of details, and you can use these details to your advantage to paint a fuller picture of an attacker’s intent, assess relative risk, and take action. Don’t forget to remember your training and refer to David Bianco’s Pyramid of Pain. It can be easy to dismiss the bottom of the pyramid, but I encourage you to get the most out of the bottom sections before rushing to higher levels. This all starts with a foundational understanding of how and why these datasets exist, and can be quickly improved with Joe Slowik’s methodology for analyzing infrastructure as composite objects. Join me for the next installment of this blog series to explore the Whois protocol.

DNS Cheat Sheet

Download the full cheat sheet (includes DNS, Whois, Passive DNS)

Additional Resources

Analyzing Network Infrastructure as Composite Objects

Formulating a Robust Pivoting Methodology

Maximizing Your Defense with Windows DNS Logging

Microsoft Sinkhole Events Report