We Know How To Prevent Ransomware

Knowing How Isn’t the Problem, Though

I’ve been involved with infosec long enough to have seen various waves of attack types be developed, have their day in the sun, and fade, as the landscape evolved. It’s almost hard to believe now, but once upon a time, denial of service attacks did not have to be massively distributed to be effective; port scans would reveal a wealth of open well-known ports to have fun with (yes, Shodan suggests this is still true, but it’s nothing like it once was); simple viruses and worms made their rounds and then were defeated by relatively simple signature-based detections, and their next-generation successors were likewise often dispatched with behavioral analysis or sandboxing. For a lot of attack types that burned bright, the story had a relatively obvious beginning, middle, and end. We all knew, of course, that as defenses became more capable, adversaries would just move on to something more effective; but there was satisfaction in seeing different malicious schemes go by the wayside as defenders got the upper hand against them.

It dawned on me recently that I’d been subconsciously waiting for that same crest-and-trough dynamic to play out with ransomware; some low-level process in my head was muttering “surely we’re going to get our arms around this one, too.” Well, it’s certainly obvious that it’s not playing out that way. If anything, we’re probably still on the wrong side of the crest. But, for all the frustration and suffering we’re enduring at the hands of ransomware gangs, the fundamentals of why we are here are not complex. We know how to prevent ransomware, we’re just not doing it.

That may sound unfairly glib, so let me clarify. First, the statement is not meant in judgment. Security teams are doing amazing work, especially in light of what the pandemic threw at them. Yes, things are bad, but they could be so much worse, and hearty credit goes to our security colleagues, from practitioners to educators to vendors. What I’m driving at is that by and large, the reason ransomware is such a persistent problem is not because it is technically extraordinary or because vulnerabilities are excessive. Acknowledging that there are some clever tools, and some thorny vulns, the reason ransomware is such a stubborn problem is that it represents the distillation of sets of tactics, techniques, and procedures that have been honed, streamlined, and commoditized. Its evolution mirrors biological evolution: what fails goes extinct, what works survives, and what adapts, thrives.

But haven’t defenses evolved, too? They have, and in some innovative and exciting ways. But the problem is analogous to the concept of entropy: there are many, many different states of disorder in which an adversary can survive and achieve objectives, whereas the successfully defended environment is an ordered state, and thus demands more energy to maintain. Malware and malicious actors, then, can evolve in an essentially limitless number of ways and achieve their goals. Defenses, on the other hand, also have to evolve, but with a relatively small number of ordered conditions being the only safe states.

Ransomware is a Shape-Shifter

With a few exceptions, the building blocks of a ransomware campaign, and the conditions of the victim environment necessary for the campaign to succeed, are very familiar. Initial access is almost always via phishing or some other method of credential theft. Lateral movement is aided by unsegmented networks and uneven controls over identity and authorization. Various stages are enabled by exploitation of known, but unpatched, vulnerabilities. Recovery is hampered by insufficient backups, or backups that turn out to be infected with the same malware that brought the network down to begin with. (Recovery also now entails dealing with the potential fallout from data leaked or sold by the ransomware actors, it must be mentioned).

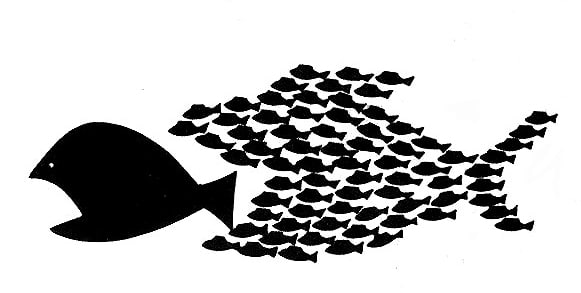

Almost every item in the previous paragraph is a problem that, in and of itself, is well understood and for which good solutions exist. What ransomware is showing us is that it is the rare environment where every box is checked. It feels like a game of Whack-A-Mole because it is very much like that. Got good phishing protection in place? Great! But legitimate credentials can leak in other ways. Got everything patched? Rock on! But privileges can be escalated without exploiting a vulnerability. Got the network segmented robustly? Excellent! But what happens when the stolen credentials get straight into a “crown jewels” subnet, or when stolen creds enable traversal of the segmented boundaries? You see the point. Ransomware is not a monolithic thing. It is a shape-shifter. It’s the big-fish-shaped school of small fish, each individually easy to dispatch, but collectively packing a big bite.

Helpful Ransomware Resources

So where does this leave us? Well, if there’s any silver lining to the ransomware crisis—and calling it such seems reasonable—it is that it has mobilized a lot of great work across both the public and the private sector to help all of us deal with it. Following are a few of the resources I have found particularly enlightening and encouraging:

- President Biden’s Cybersecurity Executive Order: while this EO does not actually mention the word “ransomware,” it does target many of the individual factors that have allowed ransomware to proliferate. It touches on thwarting cybercrime at its source, through things like improvements in information sharing, and at its destination (the victim environment) through enhancements to cloud security policies and supply chain hardening. While this applies to the federal government and not the private sector, the private sector will see some tailwinds because of it.

- NIST’s (National Institute of Standards and Technology) draft Cybersecurity Framework Profile for Ransomware Risk Management: this document takes specific components of the NIST Framework and applies them to ransomware. This document was part of the inspiration for this blog, because the individual controls and practices all relate to addressing the individual TTPs that make up typical ransomware campaigns.

- CISA’s (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) new Ransomware Risk Assessment module in the CSET (Cyber Security Evaluation Tool) is a great tool for helping organizations evaluate their security posture with respect to the ransomware threat. Some organizations will particularly appreciate the analysis dashboard feature.

- IST’s Ransomware Task Force’s report: this is the most comprehensive framework yet devised specifically to fight ransomware. It has significant recommendations for both the public and private sector, organized around four key objectives: deterring attacks, disrupting the ransomware business model, helping organizations prepare, and developing more effective responses to ransomware attacks. It is a substantial (70+ page) read, but worth the time.

- The free Playbook Viewer from Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 team: this interactive tool (which is not only focused on ransomware) gives defenders a great way to become more familiar with the TTPs used by different groups, and it’s organized around the MITRE ATT&CK framework, which helps draw a through-line from the myriad threat groups that make the news, to the exact controls the blue team needs to be on top of.

- DomainTools researcher Chad Anderson’s recent Defender’s Guide to the most prolific ransomware groups, which includes a comprehensive visual map of groups and tooling, is another fantastic way to help maintain situational awareness in the absolute blizzard of ransomware news and articles on the Internet.

The Takeaway

None of the above resources is a silver bullet, but I hope one of the takeaways here is that we don’t need silver bullets. We already have technologies and processes that are known to be effective against most of the TTPs that compose a ransomware attack. The heightened focus on the ransomware problem, and the great work being done to help defenders, may help organizations in the important work they do on their threat modeling and their security posture, and, eventually, we just might turn the tide. The ransomware story has had a beginning and middle; with some of the work described here, there is hope that it will also have an end.