Continuous Eruption: Further Analysis of the SolarWinds Supply Chain Incident

If you would prefer to listen to The DomainTools Research team discuss their analysis, it is featured in our recent episode of Breaking Badness, which is included at the bottom of this post.

Background

Multiple entities disclosed a supply chain attack via SolarWinds Orion network monitoring software on 13 December 2020. DomainTools provided initial analysis of network infrastructure and implications on 14 December. Since then, multiple entities have released reports including additional malware analysis, Command and Control (C2) identification, and details on the possible scope of the incident.

The following represent some of the more relevant items published as of this writing:

- Dark Halo Leverages SolarWinds Compromise to Breach Organizations, Volexity.

- Alert AA20-352, Advanced Persistent Threat Compromise of Government Agencies, Critical Infrastructure, and Private Sector Organizations, US Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

- SunBurst: The Next Level of Stealth, ReversingLabs.

- SUNBURST Backdoor: A Deeper Look into the SolarWinds’ Supply Chain Malware, Prevasio.

Based on additional information released by multiple parties as well as independent DomainTools analysis, this blog adds to and updates, where applicable, previous reporting.

Timeline of Events

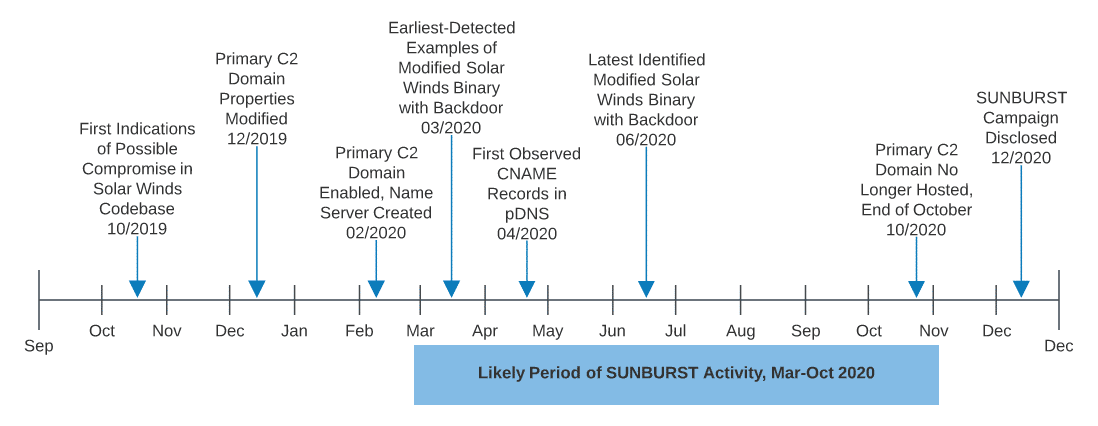

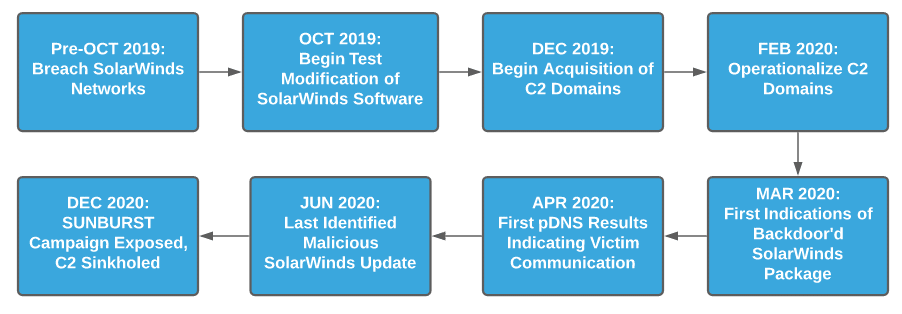

While SUNBURST activity was only identified in December 2020, analysis of campaign details and further analysis of SolarWinds software indicates the event may have started, at least in preparatory phases, over a year prior.

While previous DomainTools research shows infrastructure management and staging likely started in December 2019, subsequent analysis from ReversingLabs indicates that the operation began even earlier. Based on analysis of SolarWinds binaries, researchers at ReversingLabs identified modifications to installer packages as early as October 2019.

While this may appear to be an academic point for defenders aside from those remediating events at SolarWinds, this detail does allow us to draw several conclusions:

- The SolarWinds intrusion was a long-planned event, occurring in distinct stages: supply chain breach, software modification testing, infrastructure development, then final deployment.

- Given that this campaign appears to have started no later than October 2019, the range of possible intrusion scenarios related to this threat actor expands dramatically.

The second point is significant given reporting from Volexity—on multiple intrusions tied to the entity responsible for the SUNBURST campaign. Specifically, in several incidents the adversary—referred to as “Dark Halo” by Volexity – remained in victim environments “undetected for several years.” Based on this alarming observation, DomainTools concludes with high confidence that post-instrusion activity identified with the SolarWinds supply chain campaign has likely been active since prior to February 2020, and with medium confidence before October 2019—extending the timeline of investigation for potential victims far longer than the March to October (or later), 2020 timeline usually cited in public reporting.

Volexity’s conclusions on alternative intrusions methods are supported by recent alerting from CISA. In AA20-352, CISA noted that they possess “evidence of additional initial access vectors, other than the SolarWinds Orion platform.” In discussions with multiple parties, these vectors are beyond those detailed by Volexity, and could be related to recent reporting concerning a possible breach at Microsoft, discussed further below. As a result, organizations face an extremely difficult defensive problem given the multiple potential ingress mechanisms available to the adversary and the significant dwell time available to them following breach based on available timelines and campaign duration estimates.

Additional Infrastructure Observations

While DomainTools Iris Passive DNS (pDNS) information identified and confirmed second-stage C2 nodes provided as Canonical Name (CNAME) responses to DNS requests to the primary C2 domain, avsvmcloud[.]com, additional infrastructure continues to surface linked to the campaign. As a reminder, the following represent the first and second stage beacon domains associated with SUNBURST malicious SolarWinds Orion installer activity:

While these are reasonably well known and documented, follow-on infrastructure relates to Cobalt Strike Beacon and related post-exploitation payloads. Based on analysis from FireEye, Volexity, and Symantec-Broadcom, different sets of infrastructure—including potentially unique domains per victim—are used in this phase of events. As of this writing, DomainTools is aware of the following infrastructure linked to this campaign:

The above items are similar to the primary and secondary C2 domains used as part of the initial SolarWinds malicious update software, as well as other commonalities:

- Using “seasoned” domains with initial registration dates typically far in advance of the campaign. In most cases, it appears the adversary re-registered expired domains of interest for use in the campaign.

- Hosting via cloud service providers, including major platforms such as Amazon AWS.

- Consistent, although not exclusive, use of technology-related naming “themes” or conventions.

- Use of Sectigo-issued SSL/TLS certificates for encrypted communications mostly issued in 2020, well after the creation date of the domains.

Given the possibility that these third-stage C2 domains may be unique to individual victims, their use for direct defensive purposes (e.g., incorporating into block or alarm lists) is circumscribed. However, focusing on the observations and commonalities of the infrastructure—age, theme, hosting pattern, and significant differences between registration and SSL/TLS certificate timestamps—may work to identify similarly-structured infrastructure.

For example, an organization could use automated lookups to a resource such as DomainTools to capture information about a newly-seen, unfamiliar domain in network traffic. This information can then be parsed to compare registration and certificate times, or a combination of registrar and hosting provider or Autonomous System Number (ASN) used to identify infrastructure linked to past malicious behaviors.

Victim Identification and Defensive Notes

Another recently-popular aspect of the SolarWinds supply chain attack is victim identification through reversing the algorithm used to encode subdomains on DNS lookups to the primary C2 domain, avsvmcloud[.]com. Multiple entities have produced lists of both raw requests (including DomainTools researchers here) and decoded lists following the algorithm published by Prevasio.

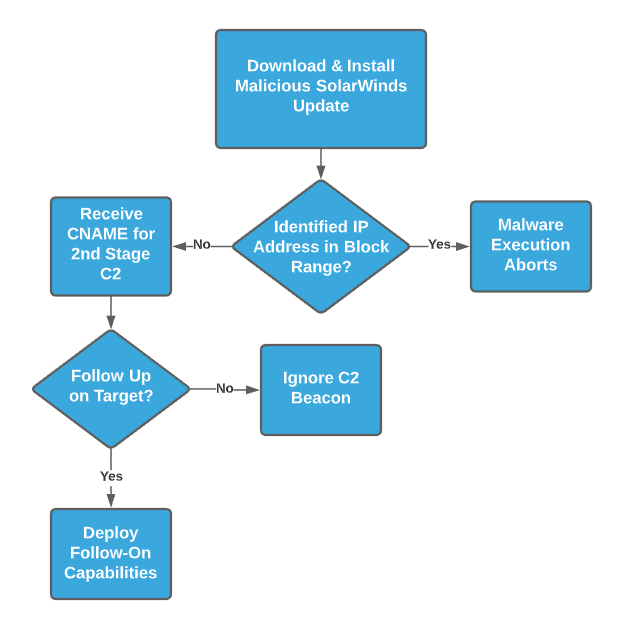

While provocative, analysts must understand the nature of the SUNBURST infection chain to appropriately grasp the nature and meaning of any purported “victim list.” As shown in the following diagram, while a beacon to the primary C2 domain is necessary for follow-on exploitation to occur, it is not sufficient given checks within the malware for network ranges and security products for further functionality.

A victim could download the malicious package and execute it, but fail one of several checks for follow-on execution resulting in an inert payload. Furthermore, even if a victim receives the CNAME for follow-on C2 behaviors, it remains up to the adversary’s discretion as to whether that entity will receive any follow-on payloads, such as Cobalt Strike Beacon or other post-exploitation tools.

Furthermore, there is another aspect of the “victim lists” which must be clearly called out. Circulated lists of “victims” are based on pDNS collection related to the primary domain, avsvmcloud[.]com. While a number of entities, including DomainTools, work diligently to collect as complete a picture of DNS queries as possible for multiple reasons, no provider has a complete view into all executed DNS queries. As a result, the list is almost certainly incomplete. The significance of this observation is that an organization not being on the list of identified victims does not mean that entity did not conduct any network traffic to campaign-related infrastructure – instead, that traffic may simply have been missed or not recorded.

Rather than relying on third-party data, defenders and IT personnel should instead leverage internal data sources and continuous DNS monitoring. These will be far more authoritative of the organization’s activity and more reliable. While third-party datasets are extremely useful for research purposes, own-network defense is best augmented through visibility of own-network activity and traffic.

A Note on Attribution

Shortly after initial disclosures on intrusions into the US Treasury Department and other organizations, media entities linked the events via sources to “APT29.” APT29, also referred to as Cozy Bear (CrowdStrike), The Dukes (various), or YTTRIUM (Microsoft), has previously been associated with Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), a successor organization to the First Chief Directorate of the Committee for State Security (KGB). However, this link is neither definite nor undisputed, as other researchers and organizations have also linked APT29 to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Notably, the last US (and other) government public reporting on APT29, concerning theft of COVID-19 information in summer 2020, only referred to APT29 as linked to “Russian intelligence services” as opposed to a specific entity.

In the case of SolarWinds and related activity, it appears US government sources, speaking with the Washington Post, linked the activity to APT29 as an alternative way of referencing SVR. This observation is interesting, as three entities have now reported on the activity in question without associating the identified behaviors with APT29:

- FireEye’s report linked the intrusion to a new entity tracked as “UNC2452,” using the company’s documented activity clustering methodology.

- Both Microsoft’s customer blog and technical reporting did not mention a specific adversary responsible for events, despite previous reporting on YTTRIUM.

- Volexity, which has previously published material directly attributing events to APT29, also linked identified activities to a new entity, similar to FireEye, only in this case named “Dark Halo.”

The overall picture is therefore confusing, as government sources are using “APT29” for this intrusion, while commercial entities that have directly responded to events are associating events with different entities. While DomainTools does not engage in direct attribution, observations and analysis of publicly available information indicate likely misunderstanding between organizations.

Based on a close reading of media reporting, it appears that sources linking activity to “APT29” may be using this term as a catch-all for SVR activity. Meanwhile, entities responding to events and with the most data at present see clear differences between the current activity and legacy APT29 behaviors. If using a behavior-based attribution methodology where naming conventions are assigned to collections of activities or behaviors as opposed to distinct entities (such as, “SVR”), having a separate naming convention for distinct behaviors makes sense

Overall, current analysis indicates that entities are almost certainly using different meanings for “APT29” in this event, with certain sources equating “APT29” with “SVR” while threat intelligence and incident response companies view possible SVR-linked cyber activities distributed among distinct groups. The one note of caution for defenders out of this confusion is that, given security company tracking as “not APT29,” standard playbooks and assumptions on APT29 behaviors and activity are not necessarily applicable for this campaign.

Defense, Mitigation, and Recovery

The identified campaign remains a difficult problem for network defenders to both identify whether a breach has taken place, and to then scope the extent of such an intrusion. Matters have gotten even worse as there are now indications that, in addition to SolarWinds, Microsoft may also have been breached as part of this activity (a claim which is disputed as of this writing). The potential scope and risk of supply chain compromises remains concerning and significant—but are not insurmountable.

For defenders and IT operators, recognizing that just deploying a capability within a monitored environment—such as the malicious SolarWinds update—is not sufficient to achieve compromise. Instead, adversaries must be able to take some measure of control over infected devices, and be able to move laterally within the network to other sources of value for collection or other objectives. All of this activity, even if initial intrusion leapfrogs a large number of controls and monitoring points, leaves traces for detection and response.

Organizations that monitor for new, unique, or abnormal network connections can identify C2 communication schema. Proper asset classification which identifies specific hosts or host-type (e.g., “server” instead of “end-user client”) can further differentiate communication to identify items of concern. Similar classification can also work to identify unusual authentication activity, where servers (such as a SolarWinds Orion device) initiate logons to other clients instead of the reverse.

Overall an emphasis on visibility, own-network understanding, and being able to correlate events together to identify suspicious patterns of activity can succeed in identifying even the most complex supply chain attacks post-breach. Although attackers may still gain initial footholds within networks, being able to dramatically reduce adversary dwell time is a significant improvement over what many organizations impacted by this SolarWinds event will experience in the coming weeks.

Conclusion

The SolarWinds breach and resulting aftershocks will continue reverberating around the security community. When additional potential supply chain intrusions—such as that allegedly taking place at Microsoft—are added in, network defenders must be extremely vigilant in monitoring and operating their networks. While circumstances may seem dire, a combination of enhanced network monitoring, own-network understanding, and enrichment of external observations through tools such as DomainTools Iris can work to minimize an adversary’s ability to evade detection, or minimize time to detection to reduce the scope of an incident.

DomainTools will continue to analyze this event and its implications, and provide further observations and recommendations as appropriate.

Read our previous blog on the SolarWinds Supply Chain Incident.