Finding Additional Indicators With a SeaTurtle Deep Dive in Passive DNS Within DomainTools Iris

Introduction

As SeaTurtle keeps on swimming with its DNS hijacking campaign—originally reported by Talos—it becomes increasingly important to monitor and examine your domains for indications of name server compromise. While security measures such as two-factor authentication, DNSSEC, and locking of your domains may be great steps, the actors behind SeaTurtle have shown that they can overcome all of those by moving laterally from tertiary vendors to exfiltrate signing certificates and credentials to DNS management services. Active monitoring is key, but additional research through passive DNS can reveal past attacks or suspicious activity on endpoints you may not normally be paying attention to in your infrastructure.

At DomainTools we’ve done extensive testing across passive DNS providers to come up with what we feel comprises the top providers, which includes our partner Farsight Security, for comprehensive breadth and timely coverage. Using this spread of vendors coupled with access to all of the other data sets in our Iris Investigate Platform, you can quickly pivot and expand to find new artifacts. In this paper we’ll take a look at the SeaTurtle IoCs reported by Talos in DomainTools Iris with further examination through passive DNS and show how we can uncover new IoCs in DomainTools data sets.

SeaTurtle Recap

Essentially the SeaTurtle campaign comes down to an initial compromise via a spearphishing email or a well-known exploit on an unpatched server. Often times the attackers leveraged an outside vendor used by the end organization. The attackers then move laterally to eventually reach their primary target —sometimes through multiple organizations—and steal credentials for issuing certificates and modifying DNS records. They then issue certificates spoofing target domains and flip the victim nameservers to point to their own nameservers that then return man-in-the-middle servers for email and other services. Attackers then harvest more credentials and exfiltrate data while continuing to cement their position with these new credential sets.

These techniques give you a couple of artifacts to look for in passive DNS. First would be the man-in-the-middle servers used to siphon credentials, their IP addresses and where they were hosted. Second, the nameservers that were swapped—both the original and the attacker-controlled nameservers. And finally, the IP addresses those nameservers pointed to and where they would be hosted. With this information you can tell from Passive DNS the duration of a man-in-the-middle attack when investigating a breach.

Additionally, you can monitor your DNS record sets for any anomalous responses falling outside your expected ASN. If the victims of SeaTurtle had been monitoring for responses that contained known ephemeral cloud hosting providers—or even just IPs outside their own range—they would have been immediately aware of the breach. This is why DNS monitoring is essential; however this core fabric of network infrastructure is often overlooked by security teams.

Looking at the Indicators

In a post-GDPR world, attribution has obviously become much more difficult. Some would say it’s been relegated to its correct place—never putting much stock in attribution to begin with—and that now we should concentrate on identifying and stopping attacks by fingerprinting infrastructure instead of relying on leaked registration details or other poor OpSec from an attacker. Regardless of your stance, identifying the infrastructure and techniques of attackers is the only way to generate a clear fingerprint of an actor or group so we will go through each of these individually to suss out key points.

Server Used

The actors behind SeaTurtle used all commodity VPS providers to host their nameservers and man-in-the-middle machines on. While that isn’t anything new or particularly interesting, the spread of providers that they used certainly is. Looking at the IoCs Talos provided we see the following spread if we look at them in Iris IP Profile tool:

| IP | ASN | GeoIP/VPS Region | Provider | Target(s) | Attack Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 199.247.3.191 | 20473 | Frankfurt, DE | Vultr | Albania, Iraq | Nov 2018 |

| 37.139.11.155 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Albania, UAE | Nov 2018 |

| 185.15.247.140 | 24961 | Dusseldorf, DE | Myloc | Albania | Jan 2018 |

| 206.221.184.133 | 23470 | Piscataway, NJ, US | ReliableSite | Egypt | Nov 2018 |

| 188.166.119.57 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Egypt | Nov 2018 |

| 185.42.137.89 | 8674 | Stockholm, SE | Netnod IX | Albania | Nov 2018 |

| 82.196.8.43 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Iraq | Oct 2018 |

| 159.89.101.204 | 14061 | Frankfurt, DE | DigitalOcean | Turkey, Sweden, Syria, Armenia, USA | Dec 2018 – Jan 2019 |

| 146.185.145.202 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Armenia | Mar 2018 |

| 178.62.218.244 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | UAE, Cyprus | Dec 2018 – Jan 2019 |

| 139.162.144.139 | 63949 | Frankfurt, DE | Linode | Jordan | Dec 2018 |

| 142.54.179.69 | 33386 | Kansas City, MO, US | DataShack | Jordan | Jan 2017 – Feb 2017 |

| 193.37.213.61 | 44901 | Sofia, BG | RedCluster (VPSag) | Cyprus | Dec 2018 |

| 108.61.123.149 | 20473 | Roubaix, FR | Vultr | Cyprus | Feb 2019 |

| 212.32.235.160 | 60781 | Amsterdam, NL | Leaseweb | Iraq | Sep 2018 |

| 198.211.120.186 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Iraq | Sep 2018 |

| 146.185.143.158 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Iraq | Sep 2018 |

| 146.185.133.141 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | Libya | Oct 2018 |

| 185.203.116.116 | 44901 | Sofia, BG | RedCluster (VPSag) | UAE | May 2018 |

| 95.179.150.92 | 20473 | Monroe, LA, US | Vultr | UAE | Nov 2018 |

| 174.138.0.113 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | UAE | Sep 2018 |

| 128.199.50.175 | 14061 | Amsterdam, NL | DigitalOcean | UAE | Sep 2018 |

| 139.59.134.216 | 14061 | Frankfurt, DE | DigitalOcean | USA, Lebanon | Jul 2018 – Dec 2018 |

| 45.77.137.65 | 20473 | Hoofddorp, NL | Vultr | Syria, Sweden | Mar 2019 – Apr 2019 |

| 142.54.164.189 | 33387 | Kansas City, MO, US | DataShack | Syria | Mar 2019 – Apr 2019 |

| 199.247.17.221 | 20473 | Frankfurt, DE | Vultr | Sweden | Mar 2019 |

| 95.179.150.101 | 20473 | Monroe, LA, US | Vultr | (Attacker Nameservers, Multiple Victims) | Jan 2019 – Still Resolving |

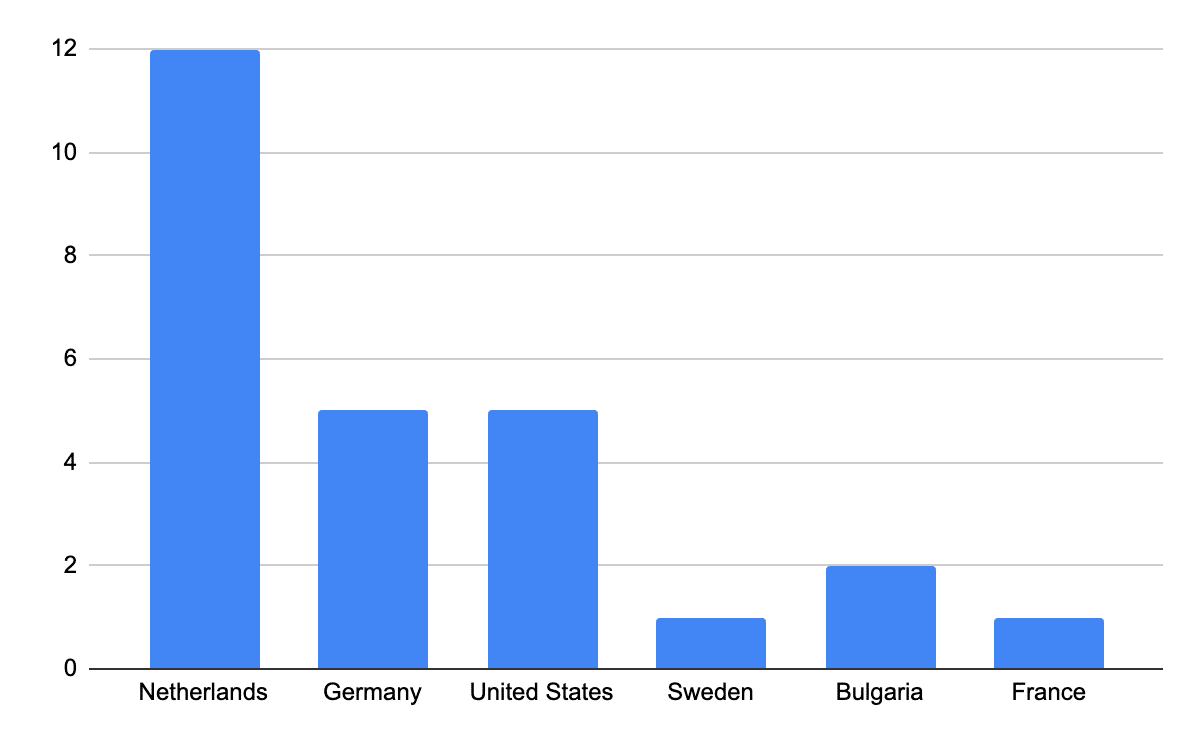

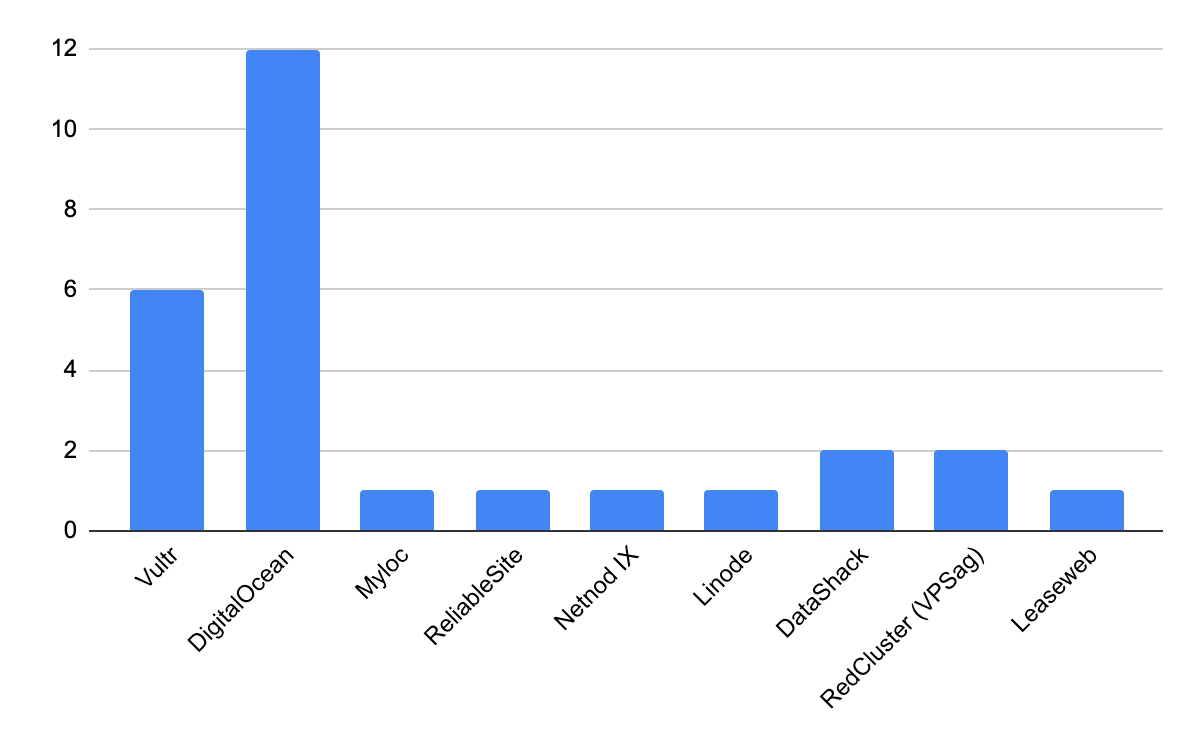

You can see below that those behind SeaTurtle overwhelmingly preferred DigitalOcean and Vultr as providers using mostly instances across all providers in the Netherlands and Germany—almost all in the EU. There are many explanations for this choice. For example, many bad actors choose those regions for legal reasons, but it’s possible that those were just where they found compromisable servers they could use for free. Either purchased or plundered, the location is an interesting indicator to stay aware of when fingerprinting these attackers.

Taking a look at campaign time or target to location used and campaign time or target to provider doesn’t reveal any additional information about these attackers and therefore limits the opportunity to fingerprint them. To get further we’re going to have to dig into more data sets than what is freely available from OSINT sources and that is where Passive DNS comes into play.

Hostnames and IP Addresses

Once DNS had been compromised the actors behind SeaTurtle would either change the A records to point to man-in-the-middle servers to harvest credentials or would entirely change over their victim’s NS records to point to their controlled nameservers then serve up new A records to man-in-the-middle servers for harvesting. In some cases, they even compromised the root nameservers. The reason for each of these different techniques with the same end goal depends on the domain’s various security features such as DNSSEC or their third-party DNS vendor MFA.

One method to unearth more information is to take the time period of the attack, look up the IoCs from the Talos report, then work backward to determine what matching query/response pairs can be found in the Passive DNS data set and to see if any additional indicators would make themselves apparent. The following shows each of the IoCs provided by Talos and the domains that appeared in our Passive DNS data sets in Iris to resolve to that IP address during the given time period. A summary of the additional analysis is given along with any additional indicators found. At the bottom will be a table of just additional IoCs if you wish to skip the details.

Executive Summary

The following is a detailed look at parsing through various bits of passive DNS data to discover or otherwise infer new indicators. In total through our research we were able to find an additional:

- 15 Actor Controlled Nameservers

- 8 IP Addresses

- 4 Man-in-the-Middle Domains

From this information, continued monitoring and pivoting can be used to find even more indicators of compromise related to the SeaTurtle attack. Due to the in-depth nature and time necessary to complete and verify further work only the following have been provided.

199.247.3.191 – Albania, Iraq

Passive DNS Domains

*.inc-vrdl[.]iq—appeared this is a test to be globally responding for all subdomains requested including ssh, firewall, git, exchange, dev, etc. Almost as if enumerating subdomains. mail[.]asp[.]gov[.]al webvpn[.]shish[.]gov[.]al reserve435432[.]drproxy[.]website

Summary of Findings

The .iq domains included here seem to be the malicious nameserver responding for all subdomains requested—almost as if someone was enumerating subdomains. Labels included firewall, git, exchange, dev and more common services.

For the .al domains the first mail domain belongs to the Albanian State Police normally on an IP of 185.71.180.6. It is worth mentioning after the attack the mail domain was pointed back at this IP. The second VPN domain belonging to the Agjencia Kombetare Shoqerise se Informacionit— roughly translated by Google as the National Agency for Information Society which sits directly under the Albanian Prime Minister’s Office and coordinates the development of the state’s information systems and guiding Albania’s state decisions in the digital age. One of their main goals is keeping up the e-Albania portal which is the electronic gateway for Albanian citizens to the government.

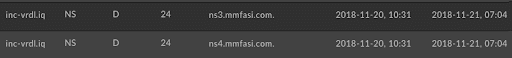

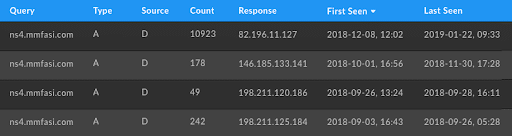

If you look at the NS records for these domains you begin to see many points at which—both during the listed attacks and at other times—the NS records were flipped to servers running on VPS hosting infrastructure from myLoc or DigitalOcean. Some of these switches correspond with other indicators that are listed in the original Talos report, but others are new. Four additional nameserver domains and two additional IP addresses can be gleaned from examining these swaps in passive DNS. For example, see the ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com nameserver below which is used by both the .iq and .al domains at one point when they were switched off of their normal nameservers. These nameservers crop up elsewhere in later indicators reviewed as well tying them to the same actors.

Additional Indicators

dns[.]cloudipnameserver[.]com resolve[.]cloudipnameserver[.]com ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com 82.196.11.127 198.211.125.184

37.139.11.155 – Albania, UAE

Passive DNS Domains

mail[.]shish[.]gov[.]al

Summary of Findings

The single domain in passive DNS for this host during this time period matches the mmfasi[.]com nameservers seen before. In addition to that, some odd nameservers— ns2[.]emailmarketer[.]ro and ns2[.]oink[.]ro—appear to spread on this IP during the campaign. Since they cannot be tied to any of the other indicators it’s possible these were compromised machines redirected here. One other domain crops up spanning the time of the attacks: demo[.]localhost[.]hu. It also cannot be tied to any of the other indicators via nameserver lookups or previous IP assignments.

Additional Indicators

None

185.15.247.140 – Albania

Passive DNS Domains

ns1[.]shish[.]gov[.]al mail[.]shish[.]gov[.]al ws1[.]shish[.]gov[.]al dns[.]cloudipnameserver[.]com resolve[.]cloudipnameserver[.]com owa[.]e-albania[.]al fs[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw edge1[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw mail[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw

Summary of Findings

This IP address contains domains that continue to attack the mail of the shish[.]gov[.]al domain as well as explicitly going after the OWA (Outlook Web Access) portal of e-albania[.]al domain. In addition to those domains are the dgca[.]gov[.]kw domains that did not appear in the original report. These appear just a few days prior and fit the pattern of attacking the mail servers. Since these domains normally lie within the Kuwaiti agency’s network or Gulfnet International networks it is odd that they end up on this IP that ties to a myLoc VPS. We feel that is enough to conclude that this IP at some point was DNS hijacking Kuwaiti domains as well. For context, the DGCA is the civilian aviation department that handles licenses for pilots, crew members, and engineers.

Looking further into these domains we see no evidence of a swap in their NS records so it must have been a simple switch of the A record from a compromised nameserver. There are no additional IP addresses to add, but we can identify the recurring theme where domains point to actor controlled nameservers. This will start to build a web throughout which all of these indicators are connected.

Additional Indicators

fs[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw edge1[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw mail[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw

206.221.184.133 – Egypt

Passive DNS Domains

mail[.]petroleum[.]gov[.]eg

Summary of Findings

At first it looks like this IP only points to the ReliableSite VPS that this Egypt IP sits on, but looking through records from a month before we can see another time that this domain was caught sending users to RedCluster—another VPS provider used by SeaTurtle in other attacks—at 185.205.210.23. This differs from the usual IP of 213.212.238.4 that this domain has had since 2010 and continued to respond to queries after the attacks.

Looking up other domains tied to that IP address we do see a lot of mail-related domains in a similar time period, but there is not enough to tie them to the rest of the SeaTurtle attacks. Included in that list though is petroamazonas[.]gob[.]ec mail domains which is interesting that they also are related to the oil industry, but looking further into NS records for those domains have no evidence of nameserver hijacking so are hard to tie in for sure.

Finally, this is the first indicator where we see use of the mentioned ns1[.]lcjcomputing[.]com and ns2[.]lcjcomputing[.]com nameservers that are actor controlled and still in use at the time of this report’s writing in December 2019. They have gone through multiple changes, but most notably they were turned “off” for almost a month while being pointed to Google’s 8.8.8.8 DNS service from March to April of 2019.

Additional Indicators

185.205.210.23

188.166.119.57 – Egypt

Passive DNS Domains

sm2[.]mod[.]gov[.]eg mail[.]mod[.]gov[.]eg mail[.]nmi[.]gov[.]eg mail[.]mfa[.]gov[.]eg

Summary of Findings

This follows the pattern of using the lcjcomputing[.]com nameservers to redirect mail servers. Here the MOD is the Egyptian Ministry of Defense, NMI is the National Management Institute and MFA is the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. All are government entities.

Additional Indicators

None

185.42.137.89 – Albania

Passive DNS Domains

dnsnode[.]netnod[.]se

Summary of Findings

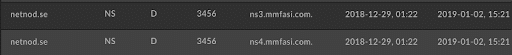

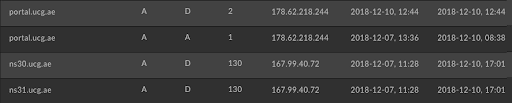

This domain does not fit the profile in the initial SeaTurtle report, but Cisco Talos may have access to a different data set. This included dnsnode[.]netnod[.]se, which does tie to another IP address in passive DNS during a time period outside of this indicator: 159.89.101.204. At a minimum this ties this domain to the attacks. Additionally of interest is the fact that at no point did dnsnode[.]netnode[.]se actually become a nameserver—according to passive DNS—for the netnod[.]se domain. In fact, what we do see is it switching to the additional actor controlled nameserver we have already found at ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com and ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com. It is possible that this dnsnode[.]netnod[.]se nameserver was never actually activated as well due to the low number of hits in passive DNS that we see for it.

Additionally, you’ll notice that netnod[.]se was once pointed to the ns1[.]frobbit[.]se nameserver, which is consistent with Cisco Talos’ report. During the time of attacks on Sweden we can see the A record for this domain switch to a Linode server at 45.56.92.19. Since the attackers only used Linode one other time during their attacks this may mean the DNS services company coincidentally uses Linode as a backup for server migrations or during upgrades.

Additional Indicators

dnsnode[.]netnod[.]se 45.56.92.19

82.196.8.43 – Iraq

Passive DNS Domains

nsa[.]gov[.]iq

Summary of Findings

Matching the report this attack looks to be targeting the National Security Agency of Iraq and again does so by swapping to the ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com and ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com nameservers during the attack.

Additional Indicators

None

159.89.101.204 – Turkey, Sweden, Syria, Armenia and USA

Passive DNS Domains

ns1[.]yorunge[.]com[.]tr ns2[.]yorunge[.]com[.]tr dnsnode[.]netnod[.]se mail[.]pch[.]net keriomail[.]pch[.]net

Summary of Findings

This seems to fall outside of the typical tactics of those behind SeaTurtle. They seem to be redirecting private companies’ DNS servers here to their own DigitalOcean server. In prior attacks they would use these tertiary vendors providing DNS services to government organizations as an initial hop into those organizations. That makes this indicator a little more interesting.

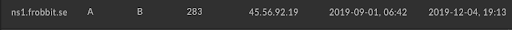

In any case, it appears that these vendors were eventually compromised. While the yorunge[.]com[.]tr domain does not have any evidence outside of its nameserver’s A records switching to the attacker controlled server, the pch[.]net domain does at one point have its NS record point to the usual ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com and ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com domains, but also has the newly appeared ns1[.]mmfasi[.]com and ns2[.]mmfasi[.]com NS records.

Considering that these were only ever on one IP—one later shared by ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com and ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com it looks like these may have been a test server before the other mmfasi[.]com NS record switches happened on other victim domains.

Additional Indicators

ns1[.]mmfasi[.]com ns2[.]mmfasi[.]com

146.185.145.202 – Armenia

Passive DNS Domains

None Matching the report.

Summary of Findings

We were unable to find any information in passive DNS that matched what the report mentioned. This could be due either to poor coverage of passive DNS sensors from providers in Armenia or perhaps this was just used as an exfiltration server or another purpose in the campaign.

Additional Indicators

None

178.62.218.244 – UAE, Cyprus

Passive DNS Domains

*[.]cyta[.]com[.]cy owa[.]gov[.]cy webmail[.]gov[.]cy govcloud[.]gov[.]cy test[.]govcloud[.]gov[.]cy m[.]govcloud[.]gov[.]cy portal[.]ucg[.]ae

Summary of Findings

The cyta[.]com[.]cy domain has dozens of responses relating to mail and admin panels and meets the usual tactic of switching to the ns1[.]lcjcomputing[.]com and ns2[.]lcjcomputing[.]com NS records for the domain before the attack then swapping in a man-in-the-middle server to presumably collect credentials.

The owa[.]gov[.]cy domain follows the same tactic, but has an additional IP address not mentioned in the report that it gets routed to later that lasts until March. This IP address—142.54.164.189—belongs to DataShack which is another VPS provider that the attackers used with other targets, but on a later attack against Syrian domains you’ll see later. This firmly ties them to that attack and deepens the web there.

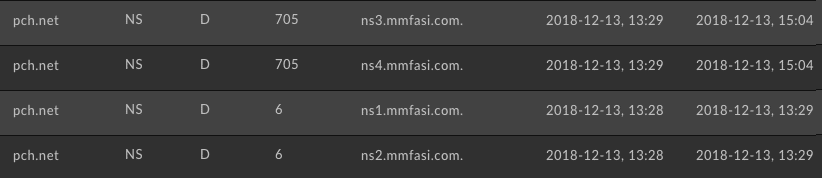

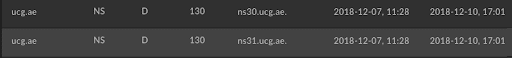

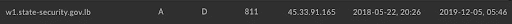

The remaining domains follow the same pattern except for portal[.]ucg[.]ae which points to this same IP at one point, but then switches to two actor spun up nameservers at ns30[.]ucg[.]ae and ns31[.]ucg[.]ae which both point to the DigitalOcean address of 167.99.40.72 during the attack. This shows that they had compromised the nameservers of ucg[.]ae, then leveraged that to put in A records to new nameservers that were close to the ucg[.]ae naming convention of ns10[.]ucg-core[.]com, then redirected all traffic through there. A different set of steps for the same result.

Passive DNS Domains

ns30[.]ucg[.]ae ns31[.]ucg[.]ae 167.99.40.72

139.162.144.139 – Jordan

Passive DNS Domains

gid[.]gov[.]jo tajneed[.]gid[.]gov[.]jo li1411-139[.]members[.]linode.com

Summary of Findings

This is the one Linode address mentioned in the report although Linode was used in other parts of the hijacking process. GID here stands for Jordan’s General Intelligence Directorate. The method follows the same here where the NS records are changed over to the actor controlled lcjcomputing[.]com nameservers.

Looking closer at these we can see that the GID has used Cloudflare for DNS since 2016. Although this attack happened at the end of 2018 there is another odd switch of their NS records in 2017 to ns1[.]cloudnamedns[.]com and ns2[.]cloudnamedns[.]com. Both of these addresses point to the same IP address (89.163.206.26) on a myLoc server—another VPS provider used by SeaTurtle. This shows us that they were compromised at least one time before the attack reported in the Cisco report.

Additional Indicators

ns1[.]cloudnamedns[.]com ns2[.]cloudnamedns[.]com 89.163.206.26

142.54.179.69 – Jordan

Passive DNS Domains

sts-dns[.]sts[.]com[.]jo mail[.]sts[.]com[.]jo dns[.]interland[.]com resolve[.]interland[.]com dns[.]cloudnameservice[.]com resolve[.]cloudnameservice[.]com

Summary of Findings

The STS here is the IT division in Jordan known as Specialized Technical Services. They handle cybersecurity and networking for the state. This follows the typical of hijacking a nameserver and redirecting to man-in-the-middle mail servers. What is interesting about this IP and what passive DNS surfaces is that we have two other sets of actor controlled nameservers that crop up following one of their naming conventions on both interland[.]com and cloudnameservice[.]com. The cloudnameservice[.]com nameservers—along with being hosted on this IP address—are also earlier hosted on 82.102.14.218 which is a IOMart (UK hosting provider) VPS address.

If we look into where those nameservers were used you can see that in 2017 primus[.]com[.]jo was also pointed to the dns[.]cloudnameservice[.]com nameserver along with sts[.]com[.]jo—likely using this initial hijacking to move to hijacking customers that use them as vendors.

Additional Indicators

dns[.]interland[.]com resolve[.]interland[.]com dns[.]cloudnameservice[.]com resolve[.]cloudnameservice[.]com 82.102.14.218

193.37.213.61 – Cyprus

Passive DNS Domains

None

Summary of Findings

No Passive DNS data could be found for the time frame mentioned for this attack in the report, but there was a owa[.]gov[.]cy query and response pair later in 2019.

Additional Indicators

None

108.61.123.149 – Cyprus

Passive DNS Domains

mail[.]defa[.]com[.]cy www[.]owa[.]gov[.]cy

Summary of Findings

These follow the usual tactic of hijacking to the intersecdns[.]com nameservers and using this IP for a man-in-the-middle server. Nothing else of import about this batch.

Additional Indicators

None

212.32.235.160 – Iraq

Passive DNS Domains

None

Summary of Findings

No passive DNS data could be found for the time frame mentioned for this attack in the report, but there are a number of Iraq domains during 2019 that fit the profile—all domains on the nsa[.]gov[.]iq network. These have already been mentioned earlier in this report so it will not be repeated here.

Additional Indicators

None

198.211.120.186 – Iraq

Passive DNS Domains

ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com

Summary of Findings

No passive DNS data could be found for the time frame mentioned for this attack in the report, but there are query and response pairs for the mmfasi[.]com attacker-controlled nameservers. Outside of that nothing new exists behind this IP address.

Additional Indicators

None

146.185.143.158 – Iraq

Passive DNS Domains

None

Summary of Findings

No passive DNS data could be found for the time frame mentioned for this attack in the report.

Additional Indicators

None

146.185.133.141 – Libya

Passive DNS Domains

ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com

Summary of Findings

No passive DNS data could be found for the time frame mentioned for this attack in the report. This was however another hosting point for the actor controlled mmfasi[.]com nameservers.

Additional Indicators

None

212.32.235.160 – Iraq

Passive DNS Domains

None

Summary of Findings

No passive DNS data could be found for the time frame mentioned for this attack in the report, but there are a number of Iraq domains during 2019 that fit the profile—all domains on the nsa[.]gov[.]iq network. These have already been mentioned earlier in this report so it will not be repeated here.

Additional Indicators

None

185.203.116.116 – UAE

Passive DNS Domains

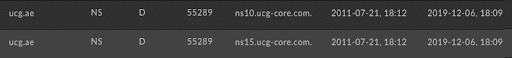

webmail[.]mofa[.]gov[.]ae jcont[.]ae

Summary of Findings

The webmail[.]mofa[.]gov[.]ae domain stands out initially as just another man-in-the-middle domain for hijacking webmail credentials for the UAE’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but digging into passive DNS will reveal something a little different. First off, this domain differs in that it never gets redirected to another nameserver that is actor controlled. Instead, we can see what looks like data exfiltration or some kind of C2 signalling through DNS. Finding out what was going on here without more network data is near impossible, but an example of the thousands of records in passive DNS during the reported time frame follows below.

The jcont[.]ae domain also shirks the usual pattern of those behind SeaTurtle attacks in that there is no NS hijacking outside of the domain’s A record itself being repointed to the RedCluster VPS IP address during the time frame of the attacks.

Additional Indicators

None

95.179.150.92 – UAE

Passive DNS Domains

webmail[.]mofa[.]gov[.]ae

Summary of Findings

This matches the above and just seems to be one of the other IP addresses that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ webmail login was redirected to at one point or another.

Additional Indicators

None

174.138.0.113 – UAE

Passive DNS Domains

nsd[.]ae mail[.]nsd[.]ae

Summary of Findings

This nsd[.]ae domain’s registration lapsed in 2019 and the attack at the end of 2018. This one stands out as odd since during the domains existence from 2013 to 2019 the only passive DNS records—or active DNS lookups we can find on A records for this domain—point to the IP address mentioned. We are unable to tie this into the rest of the SeaTurtle attacks as NSD is also not a government agency or current corporation that is registered in the Emirates.

Additional Indicators

None

128.199.50.17 – UAE

Passive DNS Domains

eft[.]efr[.]ae

Summary of Findings

This domain also lies outside the norm for other IPs mentioned in the SeaTurtle report. The domain mentioned belongs to a high end car services company. We are unable to tie this into the rest of the SeaTurtle attacks from passive DNS alone.

Additional Indicators

None

139.59.134.21 – USA, Lebanon

Passive DNS Domains

ns0[.]idm[.]net[.]lb ns1[.]isu[.]net[.]sa fork[.]sth[.]dnsnode[.]net sa1[.]dnsnode[.]net

Summary of Findings

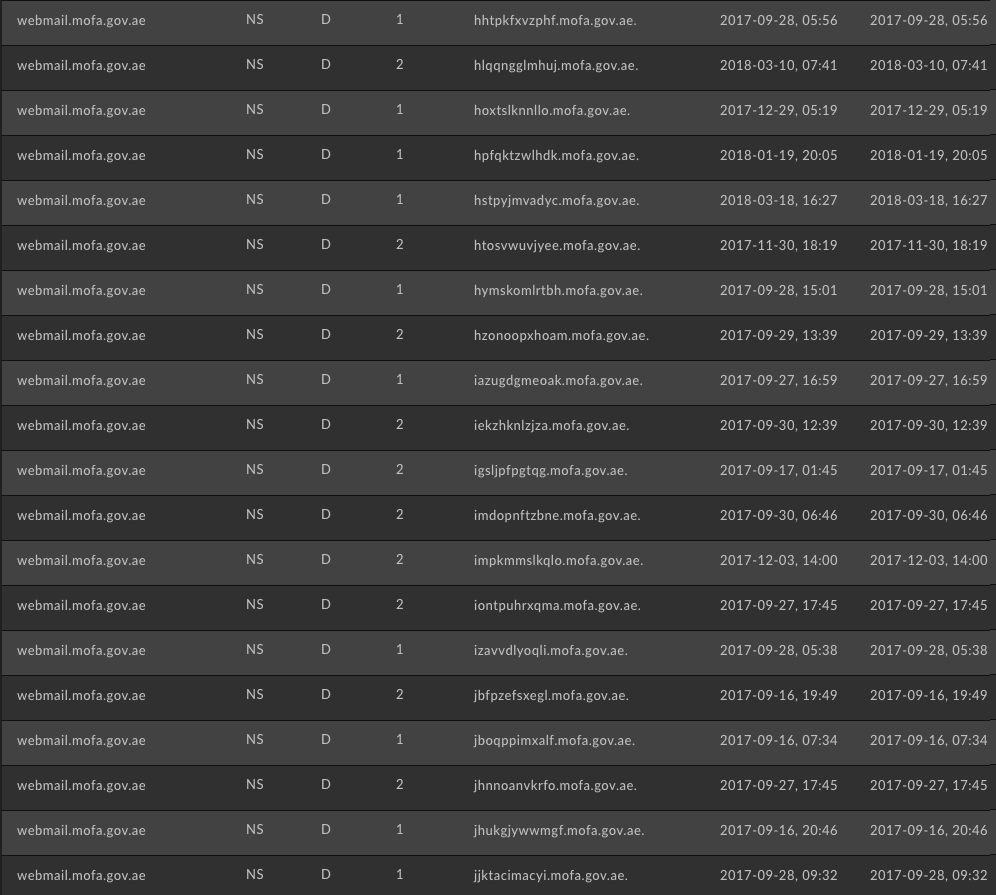

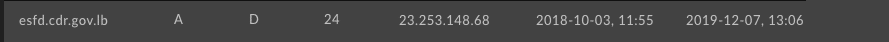

Although we were unable to find evidence in passive DNS on an attack on domains in the US, there was an interesting shift of the Lebanese nameserver here at ns0[.]idm[.]net[.]lb. This nameserver was swapped to the DigitalOcean address listed and is interesting because it manages the DNS for 1,975 domains. If we assume that SeaTurtle’s target was a government organization, than of those domains, 62 are gov[.]lb domains. Going through each of those domains in passive DNS we can find some oddities such as a domain w1[.]state-security[.]gov[.]lb which during the attack time frame pointed to a Linode address at 45.33.91.165, bdl[.]gov[.]lb pointing to a RedCluster IP address at 185.205.210.23 (which also holds an earlier gov[.]eg domain hijacking) or cdr[.]gov[.]lb pointing to a Rackspace IP address of 23.253.148.68. e believe this indicates that a number of those domains were hijacked and sent to man-in-the-middle servers for a time. Those we could find we have included as additional indicators.

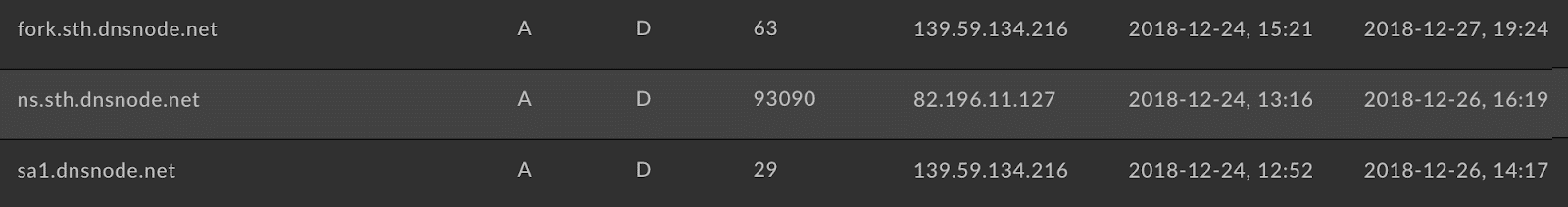

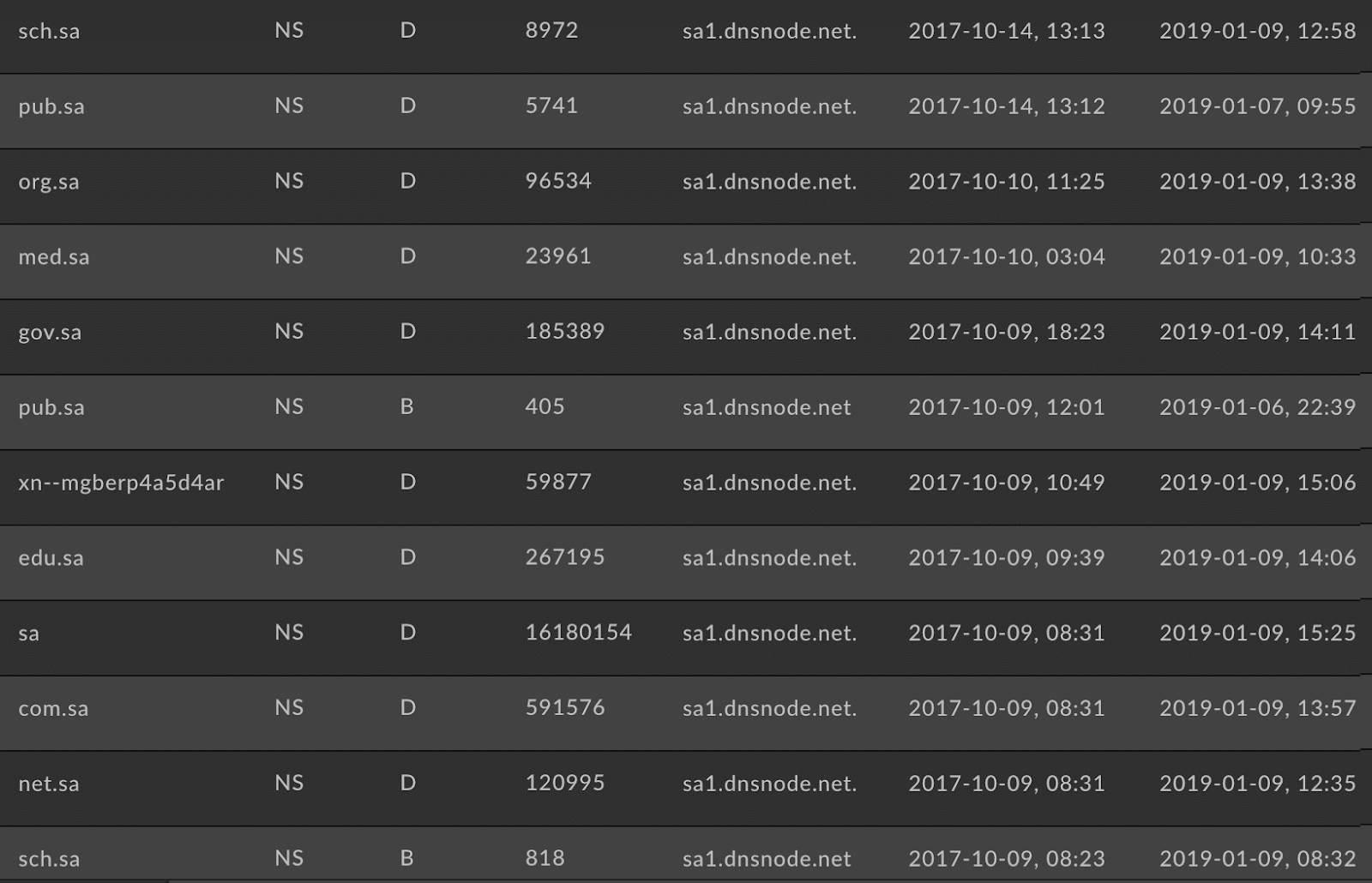

As for the sa1[.]dnsnode[.]net nameserver we can see that also being directed to the same DigitalOcean server which is the authority for all .sa domains in the Saudi Arabian ccTLD. The fork[.]sth[.]dnsnode[.]net server which also gets hijacked manages all of the .tz Tanzanian ccTLD domains. In addition, it is also the nameserver for linux[.]org—the London Internet Exchange. The sheer number of domains that trust these root nameservers makes it a herculean effort to go through and find exactly which domains were targeted for man-in-the-middle attacks, but it does show that these SeaTurtle attackers were able to take over these authoritative servers for at least a short time during 2018. This is by far— from the evidence we have—their most impressive takeover and most dangerous.

Lastly, we can see that during that same time frame the ns[.]sth[.]dnsnode[.]net server was pointed to another DigitalOcean address of 82.196.11.127. This is the exact same IP address which earlier had hosted the mmfasi[.]com nameservers controlled by those behind SeaTurtle.

Additional Indicators

45.33.91.165 185.205.210.23 23.253.148.68

45.77.137.65 – Syria, Sweden

Passive DNS Domains

email[.]syriatel[.]sy mail[.]syriatel[.]sy

Summary of Findings

SyriaTel is a mobile network provider in Syria. These email domains follow the usual pattern of hijacking the nameserver to deliver man-in-the-middle domains. The attacker controlled nameservers used are the intersecdns[.]com servers mentioned earlier.

Additional Indicators

None

142.54.164.18 – Syria

Passive DNS Domains

None

Summary of Findings

We were unable to find any domains in Passive DNS that confirmed this attack or use of this IP address.

Additional Indicators

None

199.247.17.221 – Sweden

Passive DNS Domains

nsd[.]cafax[.]se

Summary of Findings

This domain belongs to Cafax—a company that specializes in managing DNS and particularly DNSSEC. Those behind SeaTurtle likely leveraged this nameserver to attack other groups like the Talos report mentioned by getting into tertiary vendors and disabling DNSSEC. Looking in passive DNS we can see that this nsd[.]cafax[.]se domain points to a Vultr VPS. Peering at the NS records for the cafax[.]se domain we can see that on March 27, 2019 passive DNS first recorded the switch of the primary nameserver from ns[.]cafax[.]se to nsd[.]cafax[.]se. The actors must have been able to add the A record for nsd[.]cafax[.]se due to a compromise—likely at Cafax or another DNS provider—then three days later (as recorded in passive DNS) they switched to using their controlled nameservers on the intersecdns[.]com domain.

In addition to the added nsd[.]cafax[.]se domain it looks like Cafax may have previously used another DNS company to manage their DNS records named Frobbit. Looking at older NS records we see an ns1[.]frobbit[.]se and looking at NS records for cafax[.]se again we see a time when the Cafax domain’s NS was again pointed to ns1[.]frobbit[.]se. Looking further on that subdomain in passive DNS we can see that for a time in 2019—during the attack—it was also pointed at a Linode server (45.56.92.19). As this matches the tactics for the actors behind SeaTurtle we can add this IP address as an additional indicator during the 2019 attacks and as of the time of this writing it still resolves to that Linode address. This is possibly a coincidence as the attackers only used Linode one other time during the campaign.

Additional Indicators

45.56.92.19 ns1[.]frobbit[.]se

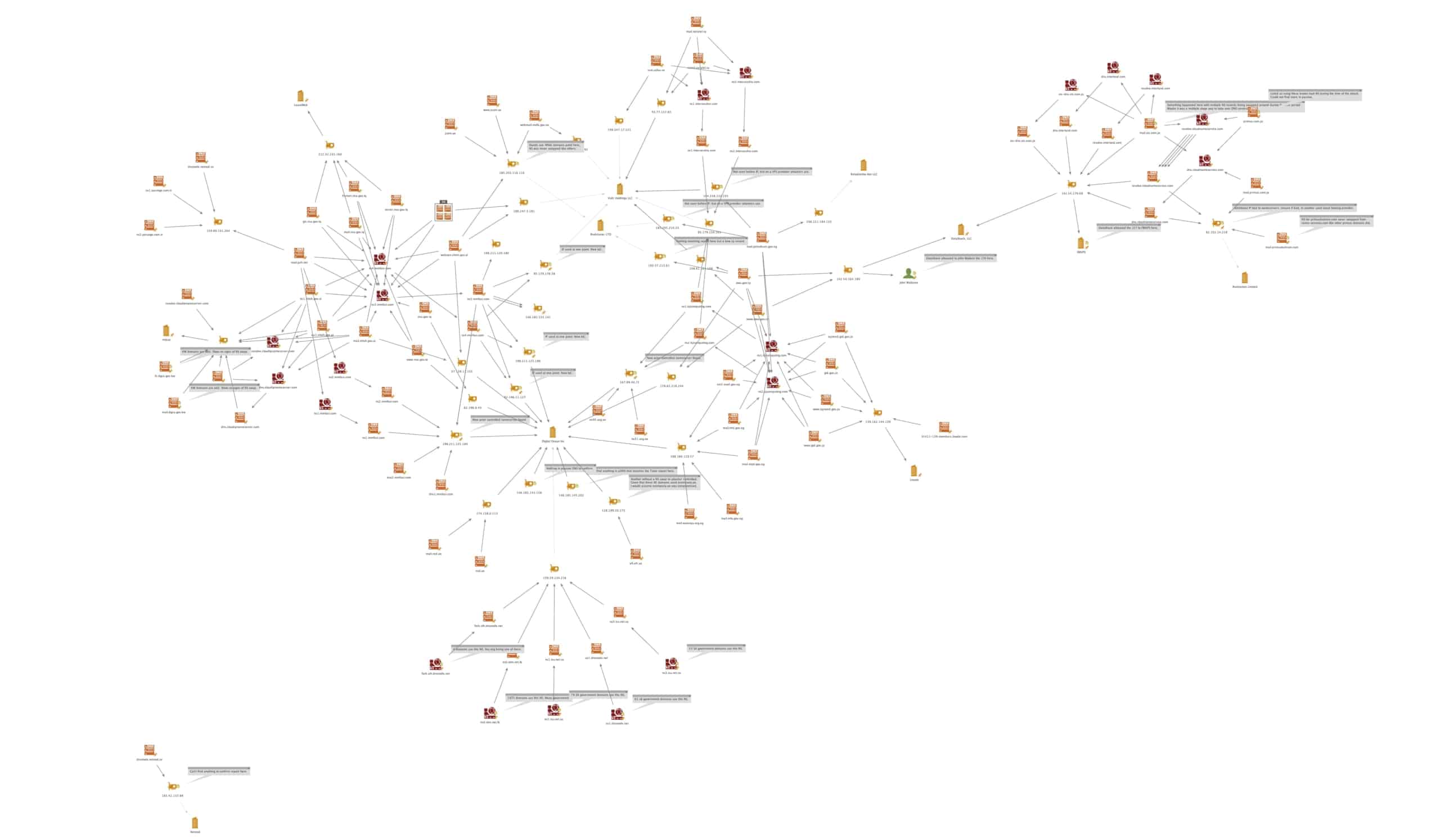

SeaTurtle Map

Summary of Additional Indicators

Additional Actor Controlled Nameservers

dns[.]cloudipnameserver[.]com resolve[.]cloudipnameserver[.]com ns1[.]mmfasi[.]com ns2[.]mmfasi[.]com ns3[.]mmfasi[.]com ns4[.]mmfasi[.]com ns30[.]ucg[.]ae ns31[.]ucg[.]ae ns1[.]frobbit[.]se ns1[.]cloudnamedns[.]com ns2[.]cloudnamedns[.]com dns[.]interland[.]com resolve[.]interland[.]com dns[.]cloudnameservice[.]com resolve[.]cloudnameservice[.]com

Additional Man-in-the-Middle Domains

fs[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw edge1[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw mail[.]dgca[.]gov[.]kw dnsnode[.]netnod[.]se

Additional IP Addresses

142.53.169.189 167.99.40.72 82.196.11.127 198.211.125.184 185.205.210.23 45.56.92.19 89.163.206.26 82.102.14.218

Conclusion

As of the time of this paper, SeaTurtle continues to effectively use these techniques to compromise various organizations and government groups. This will continue to happen as this technique remains viable and that’s why it is important to learn how to take these indicators and map them to produce more data points. From what we have done here we can see that there are many more potential actor controlled nameservers to be found and will be more in the future as those behind SeaTurtle keep using this technique. With its effectiveness will come other imitators following suit.

We at DomainTools highly recommend introducing MFA, DNSSEC and other protections for your domains alongside monitoring your DNS for any anomalies—particularly for changes in NS records.