Leaping Down a Rabbit Hole of Fraud and Misdirection

Background

While much security research and analysis focuses on active, disruptive attacks such as ransomware or state-directed espionage operations, computer-facilitated fraud remains one of the most impactful threats in terms of financial cost to most organizations. Although many varieties of fraud exist, the most prevalent at present is Business Email Compromise (BEC). In BEC events, fraudsters seek to breach or subvert trust relationships between organizations and vendors, suppliers, or other entities with which they may have a financial or similar relationship.

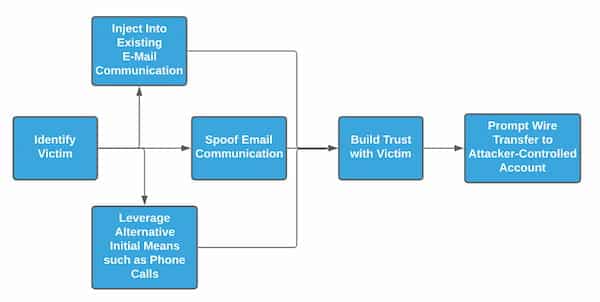

Multiple avenues exist for malicious entities to subvert trust relationships to execute BEC activity:

- Utilize compromise of an entity to capture legitimate email communications to spoof or inject into existing conversations.

- Initiate communications posing as a likely trusted entity to build trust leading to a financial transaction.

- Leverage a combination of communication mechanisms—such as blending emails with phone calls to personnel at the victim organization—to both build trust and urgency around an item.

Overall, the goal remains the same: build trust and confidence on the victim side leading to an eventual fraudulent financial transaction. While seemingly non-technical and “unsophisticated” in nature, BEC activity leads to significant financial losses. Recent reports indicate per-incident BEC events average over $80,000, with aggregate costs to victims exceeding $2 billion in 2020.

While there are multiple avenues to achieve BEC-related activity, the remainder of this post will focus on spoofing legitimate entities through domain registrations. Although directly correlating registration activity with fraud is difficult absent viewing actual emails, analysis of infrastructure characteristics can reveal tendencies aligned with BEC-like actions and identify likely malicious infrastructure.

It Started with a Domain

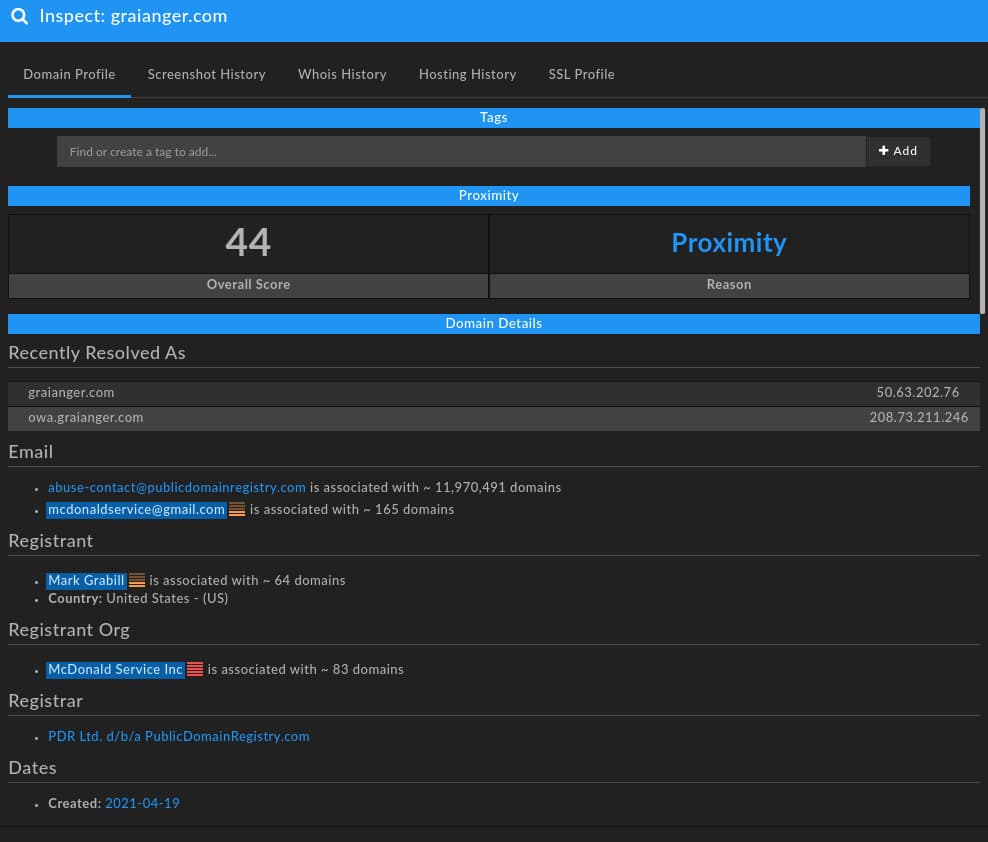

DomainTools researchers identified an interesting domain created in late April 2021, spoofing the legitimate industrial supply company Grainger:

While the domain, graianger[.]com, is associated with historical hosting data going back to 2014, the item was dormant until it was re-registered on 19 April 2021. At the time of this analysis, the domain redirects to a “parking” IP, 193.239.84[.]207, that is associated with over a thousand other domains. At first glance, it would appear this item is inactive or inert—except further exploration of DNS records identifies a Mail Exchange (MX) record associated with third-party mail provider MailHostBox.

Although at this stage no “smoking gun” exists clearly linking this domain to malicious activity, a number of prerequisites for doing so are satisfied:

- Creating a network item spoofing an organization with which a victim would likely conduct some financial transactions and linked communication.

- While the domain remains effectively unhosted for HTTP/HTTPS purposes (e.g., there is no active webpage of interest), the domain does have an active MX record through a third-party provider, enabling sending and receiving of email.

With the above in place, a fraudulent actor could send “invoice” or “purchase order” themed messages posing as the legitimate industrial supplier to victims. While the industrial supplier is not harmed through this action (except potentially loss of reputation), the violation or subversion of implicit vendor-purchaser trust can enable subsequent fraudulent financial transactions.

To gain more context on the activity in question, we can explore the characteristics of the domain—viewing it as a composite network object—to develop a better understanding for how such items are created, as well as potentially identifying linked registrations.

Expanding on Selectors

As seen in the original screenshot of the spoofing domain above, there are several observations that can be leveraged to look for linked infrastructure:

- A registrant email address, mcdonaldservice[AT]gmail[.]com.

- A registrant name, “Mark Grabill.”

- A registrant organization, “McDonald Service Inc.”

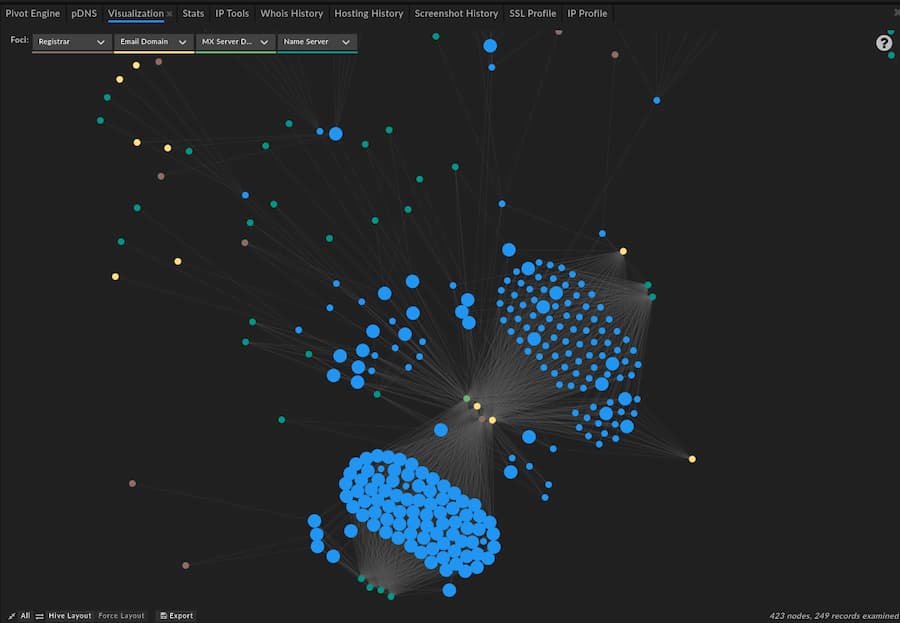

Using DomainTools Iris investigation platform, we can quickly identify a list of 249 additional domains that share one or more of these observations, listed in Appendix A. Aside from just identifying additional indicators, we also reveal more fundamental aspects of how a given persona registers, hosts, and potentially uses infrastructure. While we certainly discover new discrete observations through this process that can be used for immediate defense, this type of behavior-centric pivoting also allows us to understand behaviors moving forward for future-oriented defense.

While some underlying variation exists, the majority of records cluster around the following characteristics:

- Using the PublicDomainRegistry registrar for domain creation.

- Association with either foundationapi[.]com or monovm[.]com as authoritative name servers.

- Typical hosting on domain “parking” locations associated with M247 Europe SRL, Confluence Networks, or YHC Corporation.

- Typical use of the MailHostBox third-party email hosting service.

- Association with the following email addresses: mcdonaldservice[AT]gmail[.]com, mark.grabill001[AT]gmail[.]com, gracechen793[AT]gmail.com, m.ilenradumilo[AT]gmail[.]com, or bmillner129[AT]gmail[.]com.

Again, while there are a number of exceptions to the above observations in the identified data set, the items listed previously account for over 80% of the observed domains. From these more general characteristics, we can apply more refined searching via DomainTools Iris to unearth additional observations, and improve our understanding of how this particular entity or actor creates network infrastructure.

The above relationships—including outliers and variations—can be seen in the following DomainTools Iris visualization:

Exposing Likely Campaigns

Utilizing these characteristics described in the previous section, we can identify over 6,000 additional domains featuring a combination of these observables. More importantly, through some investigation and further analysis, definite “themes” emerge which likely represent types of activity, lures, or even particular targets for fraudulent activity.

Industrial Supply Companies

The initial item prompting this investigation related to an industrial supply company based in the United States. Further review of the list of domains identifies several other examples of similar activity:

It is possible that these domains could be used to phish the spoofed organization as a means to gain initial access to these environments. Yet, given the overall characteristics of the registering entities so far, a more likely scenario is spoofing these various industrial suppliers for the purpose of sending fake invoices or other correspondence leading to payout to the malicious actor. The above list is extensive, ranging from multinational industrial component manufacturers to diversified national supply companies to regional electric component sellers. Similarly, the risk from such activity would extend from very large organizations—such as major manufacturers, or industrial entities—to smaller contractors or specialized manufacturing concerns.

US Government Entities

A similar pattern of widespread, geographically diverse (although focused exclusively on the United States) domain creation appears with spoofing of various national, state, and local government authorities:

While a number of general, state-level domains are spoofed in the above list, the observed focus is on items related to purchasing, procurement, or IT services. From the perspective of an actor committing fraud, these represent ideal entities to impersonate when initiating communications with a business, contractor, or similar entity to mimic government procurement authorities. While DomainTools unfortunately does not have an example of a specific email related to the above items, the likely use for any of the above would be to impersonate the given agency while attempting to recover costs, reconcile billing, or perform some other financial activity.

Educational Institutions

Finally, DomainTools researchers noted a number of educational institutions in the list of mimicked items:

Similar to the government-spoofing entities identified above, these educational items could be used for a variety of purposes. Yet given the overall registration characteristics and details, likely application would be injection into existing or starting new conversations around potential cost and payment corrections resulting in a transfer of funds from a business, vendor, or contractor that already has a legitimate relationship with the institution to the fraudulent entity.

Implications and Defense

Overall, the set of identified domains leverage common registration and communication techniques to subvert existing trust relationships between vendors and customers of various types. Although superficially unsophisticated in a technical sense, the combination of required organizational understanding, social engineering, and ultimate cost to victims make these sorts of incidents extremely problematic. Even more worrying for defenders, such events do not need to leverage obviously malicious items such as malware or weaponized documents to be effective—so long as mail is delivered and responded to, the fraudsters responsible can begin building trust leading to a financial transaction.

One potential mechanism to respond to or mitigate such events is through real-time, rapid enrichment of observations to determine when they match malicious patterns. For example, utilizing a Security and Information Event Management (SIEM) system combined with auto-enrichment of observations from data sources such as the DomainTools Application Programing Interface (API) or DomainTools PhishEye can allow for rapid disposition of suspicious items such as fraudulent emails.

Examples can range from the relatively simplistic to the complex. On the simplistic end, defenders can implement detection logic in their environment to identify patterns such as “double TLDs” which frequently occur in the dataset examined in this blog. Examples include domains ending in “edu” or “gov” but then followed by another TLD such as “org” or “us.” Similar to malware using “double extensions” and other forms of masquerading, such patterns attempt to trick human interpretation to mimic a legitimate or otherwise benign item. Flagging such circumstances (or blocking them outright, if the risk is deemed sufficient) can reduce the threat of such activity.

On a more complex level, automated enrichment and evaluation can enable powerful mechanisms to detect patterns of malicious behavior. For example, most of the items identified in this report—along with a multitude of similar malicious domains—utilize the same pattern of authoritative name server, hosting provider, and MX record. When an organization can identify these characteristics of a new sender mail domain on receipt through automated enrichment, defenders can rapidly disposition these items to either flag them for further review or block them outright. Given the multitude of potential character combinations to produce typosquatting domains, being able to alert or act on the characteristics of the given sender domain as opposed to just the domain itself can be vital in architecting a robust and sustainable defensive posture.

Conclusions

BEC remains a significant risk to many organizations, with the possibility of severe financial loss resulting from successful iterations of this activity. Yet while the activity in question is purportedly “unsophisticated” by the assessment of many information security practitioners (given its reliance on social engineering and relationship spoofing as opposed to pure technical acumen), actually detecting and defeating such activity remains quite difficult.

In this posting, DomainTools researchers identified not just a methodology for uncovering likely campaigns or at least consistent actors involved in such operations, but also defensive advice for how to meet the challenge of BEC. Through understanding and analysis of adversary tendencies in creating infrastructure designed to mimic legitimate organizations, defenders can focus on the fundamental behaviors behind such activity to build defenses against future instantiations of such patterns.

By taking this forward-looking approach, which requires the ability to analyze newly-observed network infrastructure in near real-time, defenders can migrate beyond constant “backward looking” defense against fraud (and other threats). In doing so, defenders can enable sustainable, effective defense while preserving fundamental organizational value. Whether BEC or state-sponsored espionage, understanding how adversaries operate, enriching data to draw out fundamental aspects of technical observations, and creating security alerts or blocks around such an enriched perspective represent the requirements for modern, sustainable network defense.

Appendix A – Initial Domains

Download the full .csv file here.