Redefining Critical Infrastructure for the Age of Disinformation

In an era of tighter privacy laws, it’s important to create an online environment that uses threat intelligence productively to defeat disinformation campaigns and bolster democracy.

When we think of critical infrastructure in the cyber context, we tend to think about industrial control systems for power plants and water treatment facilities, or the electronic ballet box. But in today’s environment, when disinformation is a major threat vector to our national security, it’s important to expand these preconceptions.

Let’s start with the basic tenet that an informed citizenry is foundational to the integrity of a democratic system. In that context, certain sources of information — especially those outside of entertainment or commerce — can also be considered critical. The concept of a newspaper of record, which was established long ago, is a good example, along with their modern equivalents such as radio, television, and Internet media. These institutions play an important role in shaping public opinion and policy decisions.

Although news sources have always carried some degree of editorial bias, the bias in journals of record is based on an assumption that, whatever the bias, the foundation of the reported information is personal observation and recorded fact. Now that “alternative facts” have become mainstream, understanding sources of (mis)information and combating overt information warfare operations demands the rigor of critical infrastructure protection.

The Unintended Consequences of Privacy Regulations

We are also seeing the potentially detrimental effects of well-meaning privacy legislation, which has been enacted at a particularly inopportune time given the rise in fake news and election meddling. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, and the Canadian Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act are all positive steps forward in protecting citizens. But, as is so often the case, these well-intentioned efforts have unintended consequences.

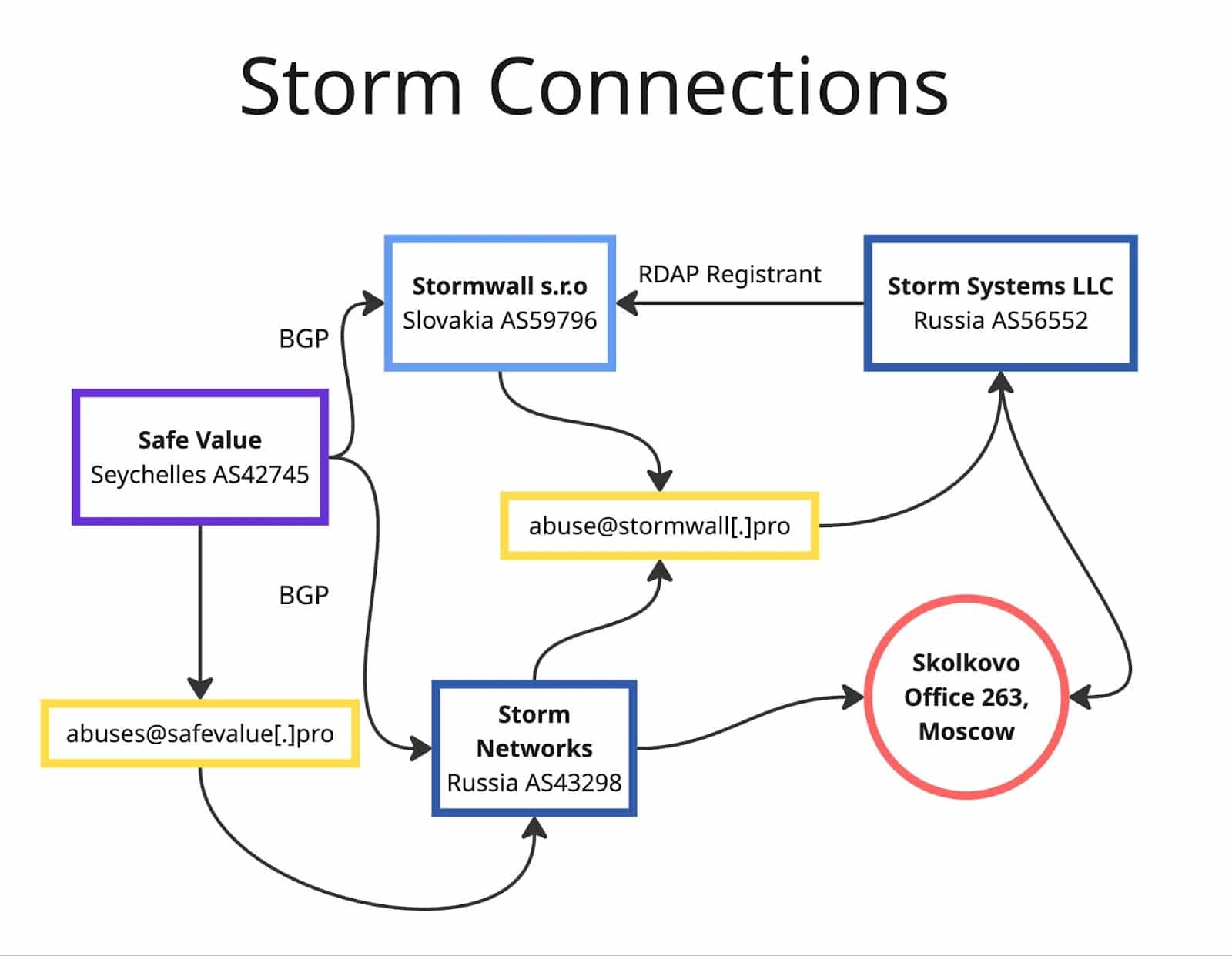

While there is no doubt that privacy regulation aims to safeguard citizens’ private data, these new laws are also hampering cybersecurity efforts — specifically, in the context of security analysts’ ability to gather and share threat intelligence about suspicious or malicious online infrastructure. As a particularly concerning example, privacy rules have taken a large bite out of the data available through the domain Whois services, making domain ownership largely opaque to investigators. This is significant, because analysis of infrastructure through a combination of DNS and registration data has been a mainstay of threat intelligence operations for years.

It’s true that threat actors have used Whois privacy for years to cover their tracks. But they have also routinely used bogus registration information to cover their tracks. Sooner or later, many of them slip up, and those mistakes help investigators and analysts crack open emerging or ongoing attack campaigns. That’s why it is critical that security researchers have access to registration and infrastructure information that can identify the actors behind cyber incidents of all kinds — including fake news campaigns and outright election tampering. Threat research from FireEye on Iranian operations further emphasizes the importance of this kind of threat intel.

This One Weird Trick to Save Democracy

OK, “save democracy” is perhaps a bit of hyperbole, but the underlying point is valid: Using threat intelligence productively in the effort to defeat disinformation campaigns is important for creating an online environment that bolsters democracy in an age of tighter privacy laws. While the removal of identifying information from domain Whois records has put a crimp in adversary infrastructure analysis workflows, it is by no means a showstopper. With the current privacy limitations on how data can be used and shared, cybersecurity professionals simply will need to understand how their efforts to combat threat actors are affected.

The good news is that analysts and hunters still can very effectively identify and combat cyber threats. But it will require going beyond Whois with shifts in long-ingrained workflows and practices used in adversary analysis. For example:

- Registration details certainly have been some of the lowest-hanging fruit for developing an actor persona or mapping a campaign. But there is a wealth of other data that can often be just as effective. Examples include DNS records (including Start of Authority, or SOA, records, which are email addresses), as well as web content such as SSL/TLS certificates, tracking codes, website titles, and screenshots. When actors create the infrastructure for an attack campaign, they often reuse many of these elements across multiple domains. It would be costly in terms of time and, in some cases money, for them to do otherwise. This is to your advantage when correlating threat actor assets.

- Remember that doxing isn’t your goal (unless you’re in law enforcement, perhaps). When trying to understand an emerging or evolving attack campaign, the most valuable aspect of attribution is to identify a persona (like a “John Doe” profile in physical crime investigations) that ties together the domains, IP addresses, web assets, malware files, and other components of the campaign. You don’t need an actual, genuine identity. Even in the days of open Whois records, it was very hard to be certain that a given identity was legitimate.

- Once a persona or correlated set of attack infrastructure has been identified, it becomes easier to take concrete actions such as searching for the discovered items (domains, IPs, URLs, etc.) in log archives or SIEMs, creating blocking rules to cover the entire campaign, or creating watchlists to monitor for ongoing evolution or expansion of the attack infrastructure.

What’s Next

The last two major US elections turned a sharp spotlight on the security (or lack of security) of the mechanisms that allow democracy to operate. Long after the votes have been counted, forensic analysis will seek to understand what, if any, impact was made by adversarial online activity, while intelligence analysis will similarly examine whether disinformation campaigns were effective in influencing electoral outcomes. The ability to comprehensively, accurately, and efficiently analyze threat actor infrastructure and campaigns is a core requirement of such work.

The good news is that there are excellent data sources, tools, and practices to enable security and intelligence professionals to shed light on, and ultimately protect against, adversaries who seek to hide in the Internet’s shadows.

Note: This piece was originally published on Dark Reading