Coming up this week on Breaking Badness. Today we discuss: It’s All Good-Faith, The Spoof is in the Pudding, and our fun new game, two truths and a lie.

Here are a few highlights from each article we discussed:

It’s All Good-Faith

- The Department of Justice today announced the revision of its policy regarding charging violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA)

- In its analysis of the DOJ change a few days ago, Andrew Crocker of the Electronic Frontier Foundation accurately described the CFAA as “the notoriously vague anti-hacking law”

- The CFAA itself states that whoever knowingly accesses a computer without or exceeding authorization and obtains information, causes damage, or supports a fraud from a protected computer is in violation of the statute

- While there are a few qualifiers, it’s written and been prosecuted in an incredibly overly-broad manner that has empowered both government and private institutions to wave it around like a big club with which to batter anyone it chooses

- In cases over the past few years the law’s scope has been limited, but previous to that, obtaining information using access you had legally, or violating the terms of service for something could put you in violation of the CFAA

- The policy lays out protections for what the DOJ describes as “good-faith testing, investigation, and/or correction of a security flaw or vulnerability” carried out in such a way as to minimize harm, promote security of the underlying device, service, or user

- It also adopts the definition of “good faith” from the Digital Millennium Copyright Act – another piece of legislation that doesn’t necessarily lead to warm fuzzy feelings in the security community

- The DOJ’s policy lays out in some specific scenarios that they won’t prosecute if they interpret the situation to be a simple terms of service violation or violating what’s considered “authorized network access” to the outside internet while at work and browsing social media

- It should be noted that most of the scenarios the DOJ lays out have already been narrowed in case law and few have to do with security research

- The particular opening we see are the references to breaking terms of service as not violating CFAA; this empowers in particular to the ability to scrape and analyze public websites, for us, and generate data and intelligence from that

- It relates back to cases where companies like Craigslist, LinkedIn, and others threatened or sued other companies for practices they didn’t like; some were predatory, some were legitimate forms of research

- This news does not mean that anyone can just claim to be “conducting security research” and pass it off as “good faith”

- The scenarios the DOJ presents are pretty narrow, and the definition of “good faith” relies on the DMCA definition, which the EFF notes is both too narrow and too vague; in particular, it prohibits methods that circumvent technological protection measures

- The article stated that the Department of Justice (DOJ) was never “interested in prosecuting good-faith computer research as a crime”, although it depends on your perspective

- There have been some pretty notable cases where CFAA prosecutions were considered by many to be overly broad, malicious, or otherwise poor decisions

- The most prominent of these is probably the case of Aaron Swartz, an internet pioneer in his own right who was charged with CFAA violations for mass-downloading JSTOR articles through MIT, including some workarounds to avoid stumbling blocks MIT put in his way

- Many folks, and many experts, considered the prosecution to be pernicious and unnecessary, and even moreso after Swartz’ suicide, which resulted in the cases being dismissed

- There was also Sony vs. George Hotz – Geohot was sued civilly under the CFAA for jailbreaking the Playstation 3; both parties settled out of court

- Geohot’s case in particular underlines the threats around security research and commercial devices

- CFAA prosecution has been threatened a number of times by companies that consider security research or other forms of analysis to violate what they consider as “authorized use” of their product, service, or site

- There are also rumblings in the data journalism world, where website-scraping or other techniques have elicited hostile threats, including a very public case recently in which an entire state apparatus mobilized to try and prosecute a journalist that used a web browser’s “view source” function, though no prosecution resulted

- We’ve got a long way to go and there’s still a whole lot of room for the CFAA to be misused by government and corporations alike, but it’s a step in the right direction

- For a deeper dive, we recommend folks review the EFF (link shared above) along with contacting your own legal professionals

The Spoof is in the Pudding

- Fraudulent domains masquerading as Microsoft’s Windows 11 download portal are attempting to trick users into deploying trojanized installation files to infect systems with the Vidar information stealer malware

- For those who may be unfamiliar with Vidar malware:

- It was first identified in 2018, and is capable of stealing sensitive data from the victim’s PC

- This includes banking information, saved passwords, IP addresses, browser history, login credentials, and crypto-wallets, which can then be transferred to the threat actor’s Command and Control (C&C) infrastructure

- ThreatLabz made this discovery via malicious domains by way of monitoring network traffic

- This is why everyone should be doing at least some level of network traffic analysis on domain names

- You can find those domain names in your DNS resolver logs, and/or in web proxy logs, SMTP logs, and sometimes other places such as smart firewalls or IDS’s, or maybe in EDR records

- They discovered these domains, with names like ms-win11[.]com, ms-win11.midlandscancer[.]com, win11-serv4[.]com, win11-serv[.]com, etc.

- To a casual observer seeing these domains in their browser window, or even to a casual security admin seeing the names whiz by in the logs, they might not raise suspicion

- But they are bad, for sure, and what ThreatLabz discovered is that those domains are designed to look just like the real Windows 11 updater sites, but they in fact are dishing out ISOs that contain Vidar

- Basically there’s a big “Get Windows 11” splash screen, and a “Download Now” button that does not download what the user thinks it downloads

- In terms of preventing this type of attack – other than noting that the URL is not an official Microsoft one—and many users might not be familiar with whether all the domains Microsoft uses are within the global umbrella of microsoft.com—there’s not a lot to see here

- The binary that it downloads is around 300 MB, of which only 3.3 MB is the actual Vidar file, and the rest is padding

- That padding makes it harder for some inline scanning products to scan (they often have file size limits) and it probably also makes it seem more realistic to the user, since you’d expect an OS update to be sizable

- This also isn’t the only attack this group is currently exercising

- They are also spoofing Adobe Photoshop and MS Teams to deliver this same malware

- We didn’t see any domain indicators given that were specifically imitating Adobe, but did see one called ms-team-app[.]net

- For the Adobe one, ThreatLabz identified an attacker-controlled GitHub repository which hosts backdoored versions of the application Adobe Photoshop Creative Cloud, and they attribute this to the same threat actor

- It’s also worth noting that some of the tooling in this campaign uses legitimate domains

- All the binaries involved in this campaign fetch the IP addresses of the C2 servers from attacker-registered social media accounts on the Telegram and Mastodon networks

- We have seen this going on for years—it’s one of the trickier kinds of traffic to spot. Not all traffic analysis is created equal, unfortunately

- We currently don’t know the extent of the damage done in this attack

- The good news is that almost all of the phony download domains have been blocked on well-known industry block lists

- But we don’t know what other infrastructure this actor may be controlling

- Time-permitting, we might open up Iris Detect to see if we can map the campaign more comprehensively

- At a quick look, it appears that the attacker covered their tracks reasonably well from the domain infrastructure perspective, but we can’t know that for sure without some additional digging

- If you’re an end-user, be really cautious about where you get your software updates

- If you’re a defender, have ways of identifying sketchy domains on your network

- It still does make sense for a lot of folks, if they have this capability, to deny traffic to newly-created domains

- The likelihood of legitimate business traffic needing to get to a brand-new domain is low enough that it may be worth it for many organizations to take the hit of the occasional service desk call when someone can’t get to a legitimate and brand-new domain

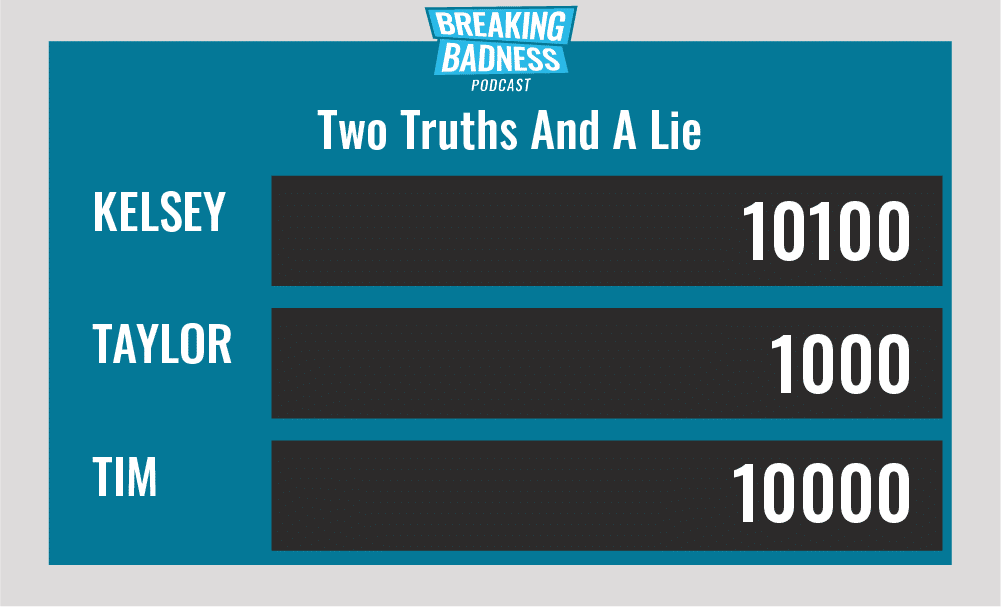

Two Truths and a Lie

Introducing our newest segment on Breaking Badness. We are going to play a game you are all likely familiar with called two truths and a lie, with a fun twist. Each week, one us with come prepared with three article titles, two of which are real, and one is, you guessed it, A LIE.

You’ll have to tune in to find out!

Current Scoreboard

This Week’s Hoodie/Goodie Scale

It’s All Good-Faith

[Ian]: 6/10 Goodies

[Tim]: 6/10 Goodies

The Spoof is in the Pudding

[Ian]: 6/10 Hoodies

[Tim]: 4/10 Hoodies

That’s about all we have for this week, you can find us on Twitter @domaintools, all of the articles mentioned in our podcast will always be included on our podcast recap. Catch us Wednesdays at 9 AM Pacific time when we publish our next podcast and blog.

*A special thanks to John Roderick for our incredible podcast music!