Coming up this week on Breaking Badness. Today we discuss: JCDC the Light at the End of the Tunnel, An Unresolved DNS-Based Vulnerability, and our fun new game, two truths and a lie.

Here are a few highlights from each article we discussed:

JCDC the Light at the End of the Tunnel

- John Turbo Conwell’s Breaking Badness Logo

- CISA is the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency which is a child agency of the Department of Homeland Security that was formed in 2018. They track and secure critical infrastructure and general cybersecurity for United States systems, providing guidance for organizations and such. Most famously their first director, Chris Krebs, was fired over Twitter by President Donald Trump after Krebs countered Trump’s arguments that voting infrastructure was secure during the election. CISA was in charge of the security of voting infrastructure.

- The Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative is designed to be a planning initiative to “up the cyber” game if you will both in planning, risk management, and national strategy as well as in the education sector. So on top of the typical laying out best practices and planning for issues that might arise they’ll also be spearheading solving this cybersecurity worker and knowledge gap. They’re bridging across both the public and private sector to make this happen.

- Along with intra-agency and ISAC partnerships, the JCDC will also be partnering with industry giants like FireEye, Crowdstrike, AWS, Palo Alto, and Google to set forth all of these plans and education initiatives.

- I find two of their core capabilities most important. The first is integrated defense of critical infrastructure. I’m not sure how they plan to achieve this, but having private critical infrastructure stakeholders share their logs and other data could be a huge boost. Transparency and sharing is key for defense and I’m excited to see the analysis and defense improvements that come from that. The other key bit was developing adaptive defense to respond to reactions from US government offensive operations. I think this is an interesting call out and provides a broad space for vulnerability research and any other sort of red team work that won’t keep the agency’s hands tied in just a pure defensive role. I wonder if it will be the piece that allows them to, say, perform work like the FBI did recently with removing webshells of vulnerable Exchange servers. Proactive defense on those critical networks in America where administrators may not be paying attention.

- CISAJen on Twitter, kills it, 20-year US Army veteran, Rhodes Scholar who did her Masters degree at Oxford. This is her initiative and she also, if you saw the keynote, can do a fantastic rendition of the Elaine dance from Seinfeld. Props to you Director Easterly. She also served on NSA’s Tailored Access Operations group and helped establish the US Cyber Command. She’s done it all plus worked in the private sector for a spell. Impressive nominee and I think that’s why no one complained when she stepped into the role.

- I am mostly excited for CISA to take up more of a role here, bridge to the private sector, provide more guidance and structured nationwide defense in the realm of cybersecurity. I am hoping we can get some good initiatives out of this that will help all of those medium to small businesses that don’t have the kinds of capabilities that larger companies do where they can hire a full time security staff or have people actively hunting for threats. Really hope to see some coordinated effort come from this that gets a lot of industry buy-in. I think if any agency is capable of it it’s going to be CISA at this point.

- JCDC’s success is going to hinge on information sharing and transparency. I think getting some sort of program going that is trusted by industry partners, where companies want—or are required to—participate if they are in certain industries. This idea of coordinated, nationwide defense can only work if some of those private sector barriers we have now are broken down. I think the way to get that buy-in is to offer access to tooling that can help raise the capabilities for all teams regardless of size. A you know, participate in telemetry kind of deal or something.

An Unresolved DNS-Based Vulnerability

- Let’s say you’ve gotten yourself a nifty new domain, and you want people to be able to visit your nifty new blog or e-commerce site. Someone has to provide the authoritative DNS services to enable that. Often, especially for small sites and blogs and such it’s just the hosting provider you go with (and sometimes hosting, domain registration, and related services like DNS are all provided in a one-stop-shopping kind of experience). But for more sophisticated or high-volume domains, or complex ones with a lot of different components residing on different servers and such, it may be easier to use a service like Amazon’s Route 53, or the DNS that comes with CDNs like Akamai. So the way it works is that you provide the domain to IP mappings in your DNS configuration, and the provider takes care of the rest, where the rest means things like making sure the servers stay up, that the zone transfers happen as they should, all of that maintenance stuff. Also, if you’re using a CDN, they’ll optimize DNS so that visitors in different regions of the globe are sent to servers closest to them for reasons of performance, language localization, and other such goodness.

- Ami and Shir got curious about what would happen if they basically spoofed a DNS server belonging to a major provider—in this case, AWS Route 53. In their article they describe registering a domain that is the same as a real Amazon name server. There’s a subtlety here if you read the article—they didn’t register that domain in the sense of owning the domain name, because the actual registrable domain portion of the hostname is in fact owned by Amazon. Instead, what they did was to create a zone file for this real DNS server that is owned by Amazon, and they did it inside Amazon’s infrastructure. It turns out that Amazon doesn’t prevent this configuration. Once they had done that, they started quickly receiving traffic from machines looking for that name server. The reason they received all of this traffic has to do with a method that Microsoft uses for updating the master server when the machine’s IP address changes (such as when you shift your remote work from home to Starbucks, which of course no security minded person would do, but still).

- They basically started this firehose of DNS traffic coming from machines all over the world—more than a million of them, they said, representing over 15,000 organizations. It was coming in from Fortune 500 companies, more than 40 US government agencies, more than 80 international government agencies…a lot of folks.

- So it turns out that DNS traffic is a little bit more complex than just “hey, what’s the IP for foobar.com?” These queries in particular were coming, as I mentioned, from Windows devices, and the scary thing about the traffic is that those Windows machines spill a lot of information about themselves as they run these queries trying to update the master server. So the researchers were seeing internal and external IP addressing schemes, employee names, computer names, office locations, basically a lot of PII that a malicious party could use in any number of ways. It would be relatively easy to pull off any number of different kinds of attacks once you had these queries in your possession.

- Given the severity of the potential consequences, I was a little surprised by what felt like a flip answer from Microsoft, saying that the queries worked the way they did because of a misconfiguration of a legitimate setting, rather than a bug. To me, that’s not quite the right answer. Microsoft is undoubtedly correct, in a narrow sense, but to me that’s a little like building a tall narrow staircase with no railing and saying “if you don’t know how to walk up stairs and you fall to your death, that’s on you.” It’s evident that this misconfiguration is extremely common. But, they point out that this wouldn’t occur if the managed DNS providers had guardrails of their own, particularly around creating zone files for domains that you don’t actually own. I personally think both parties have some responsibility here, because it’s been evident for years that there’s a LOT of room in the world of DNS registration and hosting to put illegitimate information into these services. You’ve never had to tell the truth about who you were when registering domains, hence the absolute flood of spoof domains; and now we see that you don’t even have to own the domain itself in order to receive traffic for it, in this particular case. So some more guard rails around registration and hosting might not just prevent this specific abuse scenario, but potentially could help slow down some of the other spoofing types of attacks. I say “slow down” because I realize it’s not realistic to be able to lock things down 100%. But there’s good news here – AWS and Google have, in fact, both rolled out patches to prevent this abuse mechanism, and more providers are likely following suit.

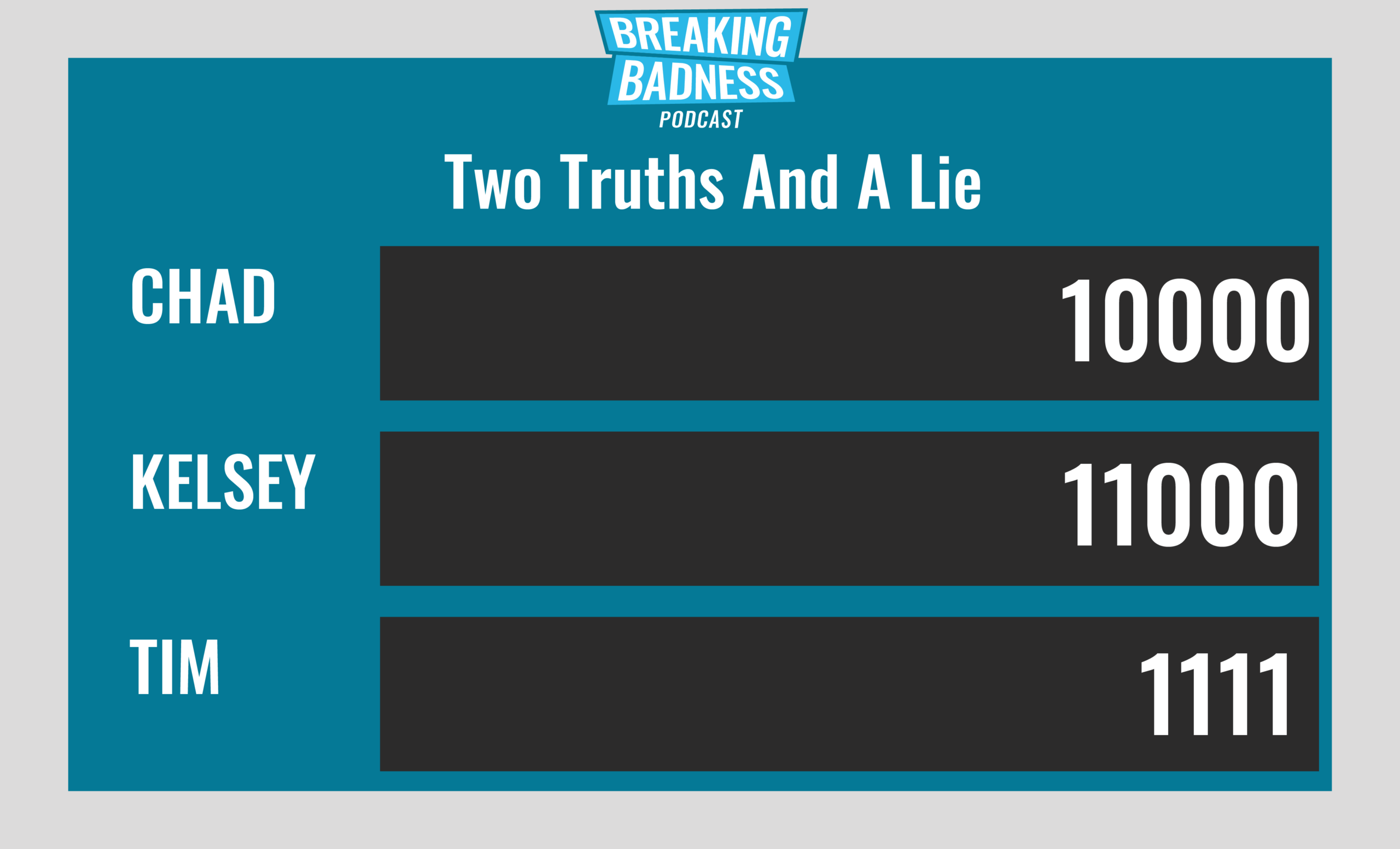

Two Truths and a Lie

Introducing our newest segment on Breaking Badness. We are going to play a game you are all likely familiar with called two truths and a lie, with a fun twist. Each week, one us with come prepared with three article titles, two of which are real, and one is, you guessed it, A LIE.

You’ll have to tune in to find out!

Current Scoreboard

This Week’s Hoodie/Goodie Scale

JCDC the Light at the End of the Tunnel

[Chad]: 8/10 Goodies

[Tim]: 8/10 Goodies

An Unresolved DNS-Based Vulnerability

[Chad]: 8/10 Goodies

[Tim]: 0/10 Hoodies

That’s about all we have for this week, you can find us on Twitter @domaintools, all of the articles mentioned in our podcast will always be included on our podcast recap. Catch us Wednesdays at 9 AM Pacific time when we publish our next podcast and blog.

*A special thanks to John Roderick for our incredible podcast music!