Change in Perspective on the Utility of SUNBURST-Related Network Indicators

If you would prefer to listen to The DomainTools Research team discuss their analysis, it is featured in our recent episode of Breaking Badness, which is included at the bottom of this post.

Background

Since initial disclosure first by FireEye then Microsoft in mid-December 2020, additional entities from Volexity to Symantec to CrowdStrike (among others) have released further details on a campaign variously referred to as “the SolarWinds event,” “SUNBURST,” or “Solorigate.” DomainTools provided an independent analysis of network infrastructure, defensive recommendations, and possible attribution items in this time period as well.

Yet, perhaps the most in-depth analysis of the intrusion at the time of this writing was published by Microsoft on 20 January 2021. Among other interesting observations, Microsoft’s most-recent reporting identified the following items:

- Incredibly high levels of Operational Security (OPSEC) displayed by the attackers to avoid identification or ultimate discovery of the SUNBURST backdoor.

- Narrowly-tailored operations with not only per-victim but even per-host unique Cobalt Strike configurations, file naming conventions, and other artifacts of adversary behaviors.

- Likely use of victim-specific Command and Control (C2) infrastructure, including unique domains and hosting IPs, to further obfuscate operations while limiting the efficacy of indicator-based analysis and alerting.

The above discoveries emphasize that an indicator-centric approach to defending against a SUNBURST-like attack will fail given this adversary’s ability and willingness to avoid indicator reuse. Furthermore, as revealed by CrowdStrike, MalwareBytes, and potentially Mimecast, we also know that the “SolarWinds actor” leverages additional initial infection vectors (most notably abuse of Office365, Azure Active Directory, and related Microsoft-based cloud services). Therefore, multiple entities aside from those using the affected versions of SolarWinds Orion software must be cognizant of and actively defending against this actor’s operations—yet a defense based on indicator alerting and blocking will fail given this actor’s OPSEC capabilities.

SUNBURST-Related Command and Control Overview

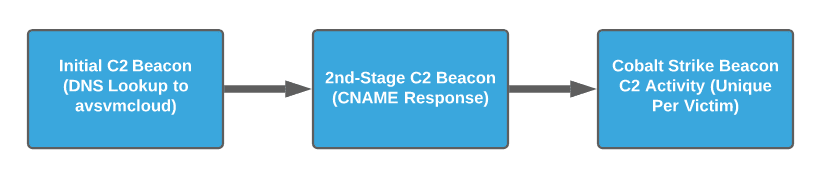

Based on reporting from multiple vendors, there was already strong suspicion that SUNBURST and related campaign network infrastructure was likely victim-specific at least during certain stages of the intrusion. As seen in the image below, for the SUNBURST-specific infection vector, C2 behaviors move through three distinct stages: the initial DNS communication to the common first-stage C2 node (avsvmcloud[.]com); the follow-on receipt and communication to a second-stage C2 node passed via a Canonical Name (CNAME) response to the initial DNS request; and finally a third-stage C2 corresponding to the Cobalt Strike Beacon payload installed on victim machines.

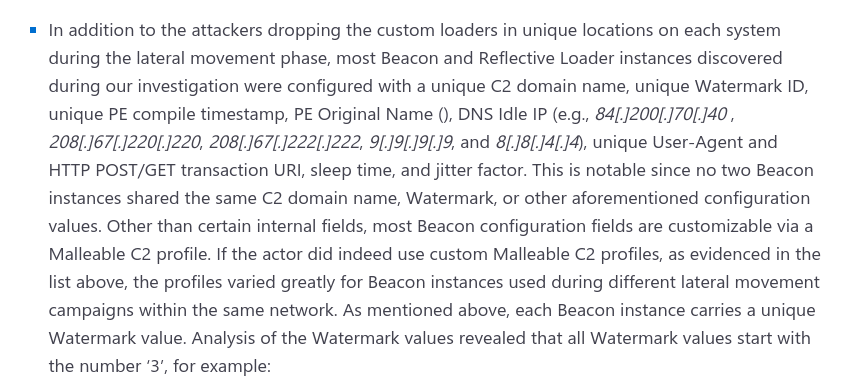

In Microsoft’s reporting from 20 January 2021, we see confirmation that while first and second stage C2 activity likely feature commonality among victims, third stage Cobalt Strike Beacon-related activity includes not only per-victim uniqueness but potentially per-host uniqueness as well:

In this scenario, individual indicators (domains or IP addresses) are effectively useless after the initial SUNBURST stages, and potentially completely impractical for non-SolarWinds infection vectors used by this adversary. Instead of Indicator of Compromise (IOC)-based defense, defenders need to migrate to identifying behavioral and infrastructure patterns to flag infrastructure potentially related to this incident.

Patterns, or the Lack Thereof

At the time of this writing, across multiple vendors, there are 29 domains with associated IP addresses linked to SUNBURST and related activity with high confidence.

| Domain | Create Date | IP | Hosting Provider | SSL/TLS Certificate | Registrar | Name Server | Purpose | First Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aimsecurity[.]net | 2020-01-23 | 199.241.143.102 | VegasNap LLC | 6a448007f05bd5069cd222611ccd1e66b4466922 | EPIK, INC.,EPIK INC | epik[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| avsvmcloud[.]com | 2018-07-25 | Various | Various Azure | N/A | NameSilo, LLC | Self | SUNBURST 1st Stage DNS C2 | FireEye |

| databasegalore[.]com | 2019-12-14 | 5.252.177.21 | MivoCloud SRL | d400021536d712cbe55ceab7680e9868eb70de4a | NAMECHEAP INC | registrar-servers[.]com | Possible Beacon C2 | FireEye |

| datazr[.]com | 2019-09-03 | 45.150.4.10 | Buzoianu Marian | 8387c1ca2d3a5a34495f1e335a497f81a8be680d | Epik, Inc. | epik[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| deftsecurity[.]com | 2019-02-11 | 13.59.205.66 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | 12d986a7f4a7d2f80aaf0883ec3231db3e368480 | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | SUNBURST 2nd Stage C2 | FireEye |

| digitalcollege[.]org | 2019-03-24 | 13.57.184.217 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | fdb879a2ce7e2cda26bec8b37d2b9ec235fade44 | Stichting Registrar of Last Resort Foundation | registrar-servers[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| ervsystem[.]com | 2018-02-04 | 198.12.75.112 | ColoCrossing | 0548eedb3d1f45f1f9549e09d00683f3a1292ec5 | Epik, Inc. | epik[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Symantec |

| financialmarket[.]org | 2001-10-02 | 23.92.211.15 | John George | a9300b3607a11b51a285dcb132e951f03974da27 | Namesilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| freescanonline[.]com | 2014-08-14 | 54.193.127.66 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | 8296028c0ee55235a2c8be8c65e10bf1ea9ce84f | NAMECHEAP INC | registrar-servers[.]com | SUNBURST 2nd Stage C2 | FireEye |

| gallerycenter[.]org | 2019-10-10 | 135.181.10.254 | Hetzner Online GmbH | a30c95b105d0c10731c368a40d5f36c778ef96e6 | NAMESILO, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| globalnetworkissues[.]com | 2020-12-16 | 18.220.219.143 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | ff883db5cb023ea6b227bee079e440a1a0c50f2b | Key-Systems GmbH | registrar-servers[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| highdatabase[.]com | 2019-03-18 | 139.99.115.204 | OVH Singapore | 35aeff24dfa2f3e9250fc874c4e6c9f27c87c40a | NAMESILO, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | SUNBURST 2nd Stage C2 | FireEye |

| incomeupdate[.]com | 2016-10-02 | 5.252.177.25 | MivoCloud SRL | 4909da6d3c809aee148b9433293a062a31517812 | NAMECHEAP, INC | registrar-servers[.]com | Possible Beacon C2 | FireEye |

| infinitysoftwares[.]com | 2019-01-28 | 107.152.35.77 | ServerCheap INC | e70b6be294082188cbe0089dd44dbb86e365f6a2 | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Symantec |

| kubecloud[.]com | 2015-04-20 | 3.87.182.149 | Amazon Data Services NoVa | 1123340c94ab0fd1e213f1743f92d571937c5301 | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| lcomputers[.]com | 2002-01-27 | 162.223.31.184 | QuickPacket LLC | 7f9ec0c7f7a23e565bf067509fbef0cbf94dfba6 | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| mobilnweb[.]com | 2019-09-28 | 172.97.71.162 | Owned-Networks LLC | 2c2ce936dd512b70f6c3de7c0f64f361319e9690 | NAMECHEAP INC,NAMECHEAP, INC | registrar-servers[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Palo Alto |

| olapdatabase[.]com | 2019-07-01 | 192.3.31.210 | ColoCrossing | 05c05e19875c1dc718462cf4afed463dedc3d5fd | NAMESILO, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| panhardware[.]com | 2019-05-30 | 204.188.205.176 | SharkTech | 3418c877b4ff052b6043c39964a0ee7f9d54394d | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | Possible Beacon C2 | FireEye |

| seobundlekit[.]com | 2019-07-14 | 3.16.81.254 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | e7f2ec0d868d84a331f2805da0d989ad06b825a1 | NAMECHEAP INC | registrar-servers[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| solartrackingsystem[.]net | 2009-12-05 | 34.219.234.134 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | 91b9991c10b1db51ecaa1e097b160880f0169e0c | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| swipeservice[.]com | 2015-09-03 | 162.241.124.32 | Unified Layer | 9aeed2008652c30afa71ff21c619082c5f228454 | NAMECHEAP INC,NAMECHEAP, INC | registrar-servers[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| techiefly[.]com | 2019-09-24 | 93.119.106.69 | Tennet Telecom SRL | ab94a07823d8bb6797af7634ed1466e42ff67bfb | EPIK, INC.,EPIK INC | epik[.]com | CobaltStrike Beacon C2 | Microsoft |

| thedoccloud[.]com | 2013-07-07 | 54.215.192.52 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | 849296c5f8a28c3da2abe79b82f99a99b40f62ce | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | SUNBURST 2nd Stage C2 | FireEye |

| virtualdataserver[.]com | 2019-05-30 | Various | Various | 4359513fe78c5c8c6b02715954cfce2e3c3a20f6 | Epik, Inc | Various | Unknown | Palo Alto |

| virtualwebdata[.]com | 2014-03-22 | 18.217.225.111 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | ab93a66c401be78a4098608d8186a13b27db8e8d | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| webcodez[.]com | 2005-08-12 | 45.141.152.18 | M247 Europe SRL | 2667db3592ac3955e409de83f4b88fb2046386eb | NAMECHEAP INC | monovm[.]com | Unknown | Volexity |

| websitetheme[.]com | 2006-07-28 | 34.203.203.23 | Amazon Technologies Inc. | 66576709a11544229e83b9b4724fad485df143ad | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | SUNBURST 2nd Stage C2 | FireEye |

| zupertech[.]com | 2016-08-16 | 51.89.125.18 | OVH SAS | d33ec5d35d7b0c2389aa3d66f0bde763809a54a8 | NameSilo, LLC | dnsowl[.]com | Possible Beacon C2 | FireEye |

Using previous DomainTools research as a guide, we can identify some “weak” patterns, such as clustering around certain registrars, authoritative name servers, and hosting providers when these items were active—note that most of the items on this list are currently sinkholed. Yet the identified patterns are somewhat weak and overlap with a number of other activities, both legitimate and malicious, making pivoting and further infrastructure discovery very difficult, if not outright impossible.

From a Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) perspective, pivoting and indicator analysis may seem to be a dead-end. The following items hold, to a greater or lesser extent, for all observed domains in this campaign:

- The use of what appear to be older domains (re-registered, potentially “taken over” by the threat actor, or potentially part of a “stockpile” of infrastructure kept for later use).

- Reliance on cloud hosting providers (such as Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure) for domain hosting.

- Use of relatively common (if also typically suspicious) registration patterns to likely “hide” in the noise of domain registration activity.

Combined, these observations make enrichment seem, on its face, somewhat pointless.

However, while these items may be difficult or impossible to use from either a predictive (identifying new infrastructure) or historical (identifying infrastructure used by the adversary, but not previously associated to it in an identified incident) external CTI analysis perspective, there remain options for network defenders. Most significantly, the patterns identified in the items observed to date, though insufficient for external discovery on its own, may be more than sufficient for internal defensive response and alerting purposes.

Operationalizing Network Observables for Active Defense

Changing our perspective from external analysis to internal enrichment of observables yields interesting and powerful detection scenarios. In the case of SUNBURST and related intrusions, the adversary succeeds in subverting critical trust relationships (with SolarWinds Orion or Microsoft cloud services) to attain initial access to victim environments. But in order to actually take advantage of this subversion, the adversary requires some mechanism of communicating with and controlling the deployed capability. At this stage, defenders can take advantage of this critical attacker dependency to identify that something is amiss.

One simple way of approaching the subject would be to flag new, unknown domains referenced in network communications for further scrutiny. This may sound potentially useful at first, but given the vast diversity of domains and the likely noise generated by user activity (or even programmatic actions), such an approach dooms itself rapidly to alert fatigue and failure.

Yet this just represents a barely enriched, minimal context way of observing network infrastructure items referenced in an organization’s overall network communication activity. If we, as defenders and responders, can add additional context and nuance to observed items and utilize this for alerting purposes, powerful possibilities emerge. Combining internal network understanding with automated observable or indicator enrichment enables rapid, contextual network defense which can quickly identify suspicious communication patterns.

For example, rather than simply responding to any instance of “new” network items observed, organizations may limit this response to critical services, servers, or network enclaves (e.g., the subnet containing various infrastructure devices). Proper network segmentation, asset identification and asset tagging to identify critical items, such as SolarWinds Orion servers or various items such as email servers or Domain Controllers, can allow for focused response when a significant asset initiates a previously unseen external connection.

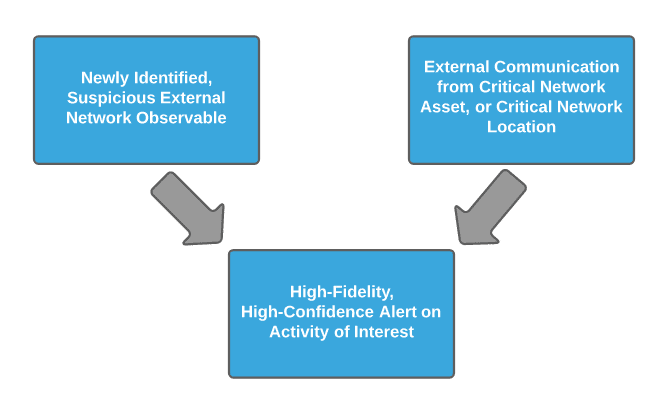

From a network observable perspective, just identifying that something is “new” can be replaced with enrichment to identify observable characteristics of interest: hosting provider, hosting location, registrar, authoritative name server, or SSL/TLS certificate characteristics. Identifying and alerting on combinations of these through automated enrichment—such as through DomainTools Iris Enrich or security monitoring plugins such as DomainTools integration with Splunk—can allow for higher fidelity, higher confidence alarms related to observed network communications. In the case of the SUNBURST-related items, even the per-victim unique items associated with follow-on CobaltStrike activity, identifying domains matching certain criteria in terms of name server and registrar associated with historical suspicious activity combined with the new observation can enable security teams to vector resources for follow-on investigation based on the greater level of detail provided.

For a truly game-changing defensive posture that fully amplifies defender advantages in both owning the network and monitoring activity emerging from it, these perspectives can be combined. In this scenario, high-confidence alerting on suspicious external network items post-enrichment is fused with internal asset identification to narrow this communication to a high-value asset or sensitive enclave within the network. The subsequent alert represents a truly critical alarm enriching on both target and adversary infrastructure aspects to focus response and drive an ensuing investigation.

Conclusion

The theoretical alerting scenario described above, where internal and external enrichment are combined to yield high-confidence, high-fidelity alarms, may appear out of reach for many organizations—but given advances in adversary tradecraft, it represents where we as defenders must drive operations. Although initially difficult to create, given both the network engineering and segmentation requirements for an accurate asset or network enclave detection, as well as the establishment of logging and enrichment pipelines for observed network indicators, once in place, an organization will find itself on a much more robust and powerful security footing.

Once attained, even the most complex and stealthy attacks such as the trust-abusing intrusions linked to SolarWinds and Microsoft services can be detected. While subsequent investigation and analysis may remain hard, as highlighted in Microsoft’s January 2021 analysis, at the very least defenders now have an opportunity to investigate and search for further signs of malicious activity within the network. Absent the enrichment scenarios described above, defenders yield own-network advantages and investigation initiative to intruders, and place themselves in a position where an adversary mistake or migration away from high-OPSEC activity is necessary to enable detection and response.

By combining own-network understanding and identification with automated indicator enrichment through services such as DomainTools, defenders can take back the initiative from intruders and detect or even cut off initial C2 beacon activity. In this manner, defenders not only adapt to but can disadvantage intruders to shift the landscape of network defense back in the network owner’s favor.